You’re driving through the high desert near Flagstaff, looking at the San Francisco Peaks, and you probably think you’re just looking at a pretty mountain range. Most people do. But if you look at a volcanoes in Arizona map, you’ll realize you are actually standing in the middle of a massive, sleeping volcanic field that has fundamentally shaped the American Southwest. Arizona isn't just about the Grand Canyon or cacti. It's about fire.

Honestly, the sheer scale of volcanism in the Grand Canyon State is enough to make your head spin. We aren't talking about ancient, billion-year-old history that doesn't matter anymore. We’re talking about eruptions that happened while humans were already living here, building homes and farming the land. It’s a living landscape.

Seeing the Big Picture on the Volcanoes in Arizona Map

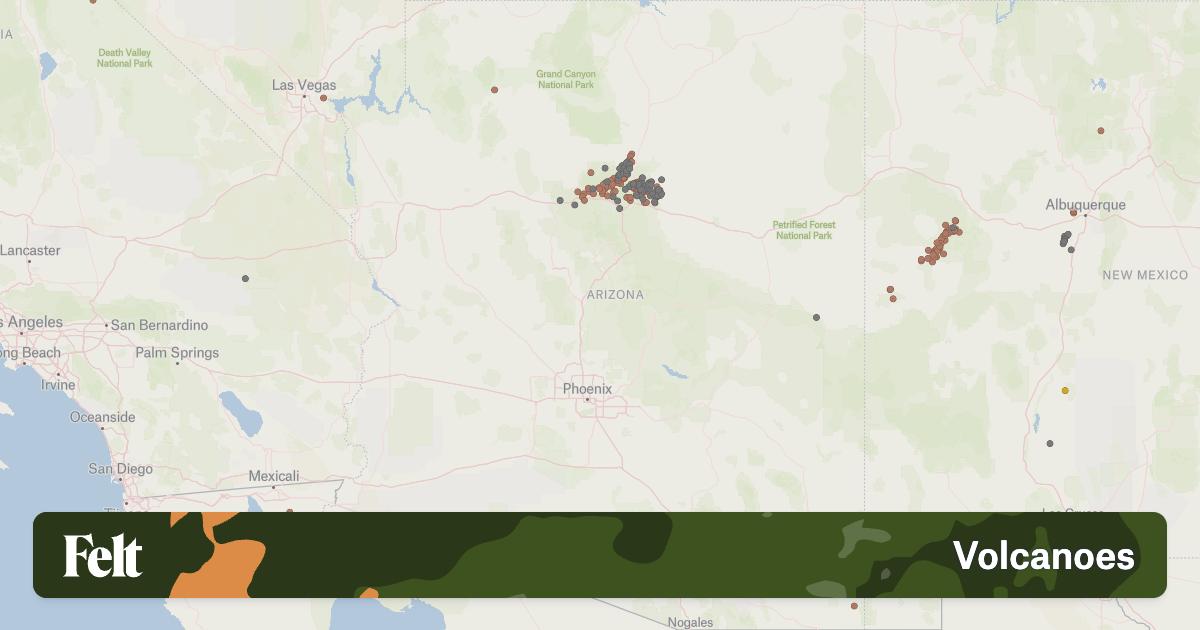

When you pull up a volcanoes in Arizona map, the first thing that jumps out is the concentration. It isn't random. Most of the action is clustered along the transition zone between the Colorado Plateau and the Basin and Range province. This is where the earth’s crust has been stretched thin, allowing magma to leak through like water through a cracked pipe.

The San Francisco Volcanic Field is the big one. It covers about 1,800 square miles. That’s a lot of ground. Within that space, you’ve got over 600 individual volcanoes. Most are cinder cones—those classic, symmetrical hills that look like someone poured a giant pile of black sand in the middle of the woods. But there’s also Humphreys Peak, which is a stratovolcano. It stands at 12,633 feet. It’s the highest point in the state, and it used to be even higher before a massive eruption blew its top off thousands of years ago.

Sunset Crater: The Youngster of the Group

Sunset Crater is the celebrity of the Arizona volcanic world. It’s young. In geologic terms, it was born yesterday. Around 1085 AD, the ground literally split open. Imagine being a Sinagua farmer living nearby. One day you’re planting corn, and the next, the earth is screaming.

The eruption at Sunset Crater changed everything. It spread ash across 800 square miles. For a while, this was actually a good thing—the ash acted as a mulch, holding moisture in the soil and allowing crops to thrive in the dry climate. But eventually, the wind blew the ash away, or it got too thick, and the people had to leave. You can still see the lava flows today. The Bonito Lava Flow looks like it cooled five minutes ago. It’s jagged, sharp, and totally alien.

The Uinkaret Volcanic Field: When Lava Met the Colorado River

If you head over to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, the volcanoes in Arizona map takes you to the Uinkaret Volcanic Field. This place is wild. Imagine a wall of molten rock pouring over the rim of the Grand Canyon like a fiery waterfall. Because that’s exactly what happened.

💡 You might also like: Lava Beds National Monument: What Most People Get Wrong About California's Volcanic Underworld

Lava falls.

Over the last 800,000 years, eruptions here sent massive flows into the canyon. These flows were so huge they actually dammed the Colorado River. We’re talking about natural dams hundreds of feet high. Behind these dams, massive lakes would form, stretching back into Utah. Eventually, the river would win, the dam would fail, and a catastrophic flood would rip through the canyon. This happened over and over again. Vulcan's Throne is the most iconic remnant of this era, a cinder cone perched right on the edge of the abyss.

Pinacate and the Southern Fields

It isn't just the north, either. Down south, near the border, you have the Pinacate volcanic field. Most of it is in Mexico, but the volcanic activity ignores borders. This area is famous for its "maars"—huge, shallow craters formed when magma hits groundwater and basically creates a giant steam explosion.

- Sentinel Plain: Flat, basaltic flows near Gila Bend.

- San Bernardino Volcanic Field: Down in the southeastern corner near Douglas.

- Springerville Volcanic Field: The third-largest in the U.S., with over 400 vents.

Each of these spots tells a different story. Some are "one-and-done" monogenetic fields, where a volcano erupts once and then dies forever. Others are more complex. But they all point to a state that is geologically restless.

Is Arizona Still Active?

This is the question everyone asks. Is a volcano going to pop up in someone's backyard in Phoenix tomorrow? The short answer is probably not tomorrow, but geologically? Yeah, Arizona is active.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) monitors these areas. They don't expect an eruption in our lifetime, but the probability isn't zero. The San Francisco Volcanic Field has been active for about 6 million years. The eruptions have generally moved from west to east over time. Sunset Crater is the easternmost major vent. If a new volcano were to form, it would likely be even further east, perhaps toward the town of Winslow.

📖 Related: Road Conditions I40 Tennessee: What You Need to Know Before Hitting the Asphalt

The state’s "active" status comes from the fact that there have been eruptions within the last 10,000 years. That’s the benchmark. Since Sunset Crater erupted less than 1,000 years ago, Arizona stays on the list of states with active volcanic potential.

Navigating the Map for Your Next Trip

If you want to actually see this stuff, you need to get out of the car. A volcanoes in Arizona map is a great start, but the texture of the basalt and the smell of the ponderosa pines on a cinder cone are something else.

Start at Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument. Take the Lava Flow Trail. It’s a short loop, maybe a mile, but it puts you right at the base of the cone. You can see the "squeeze-ups"—blobs of lava that were pushed through cracks like toothpaste. Then, drive up to the San Francisco Peaks. If you hike to the top of Humphreys, you’re standing on the remains of a mountain that once rivaled the biggest peaks in the Cascades.

- SP Crater: This is on private ranch land (with public access allowed usually) north of Flagstaff. It’s a perfect cinder cone with a massive, distinct lava flow that looks like a giant tongue licking the desert floor.

- Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument: This is remote. Very remote. You need a 4x4 and a lot of water. But seeing the volcanic flows at Mt. Trumbull is a religious experience for geology nerds.

- Agua Fria National Monument: South of Flagstaff, this area features massive basalt mesas that were once liquid fire.

The Cultural Impact of Arizona's Volcanoes

We can't talk about the volcanoes in Arizona map without talking about the people who were here first. The Hopi, Zuni, and Navajo (Diné) tribes have deep spiritual connections to these mountains. The San Francisco Peaks are sacred. They aren't just "volcanoes" to the people who have lived in their shadow for centuries; they are the homes of deities and the source of life-giving water.

Oral traditions among the Hopi actually describe the eruption of Sunset Crater. They remember the "fire in the sky." This isn't just archaeology; it's living history. When you visit these sites, you're walking on ground that is woven into the identity of the Southwest.

Why It Matters Today

Understanding the volcanic layout of Arizona helps us understand the water. Volcanic rock is porous. When snow melts on the peaks, it doesn't just run off; it sinks into the ground, filtering through layers of ash and basalt. This recharges the aquifers that cities like Flagstaff rely on. No volcanoes, no water. No water, no Arizona as we know it.

👉 See also: Finding Alta West Virginia: Why This Greenbrier County Spot Keeps People Coming Back

The landscape is also a playground for scientists. NASA has used the volcanic fields around Flagstaff to train astronauts for decades. The Cinder Hills were used to test the Lunar Rover because the terrain so closely mimicked the surface of the moon. If you’re a space geek, the Arizona volcanic map is basically a map of early space exploration history.

Practical Steps for Volcanic Exploration

If you're planning to use a volcanoes in Arizona map to guide a road trip, here’s how to do it right. Don't just stick to the interstate.

Grab the right gear. Volcanic rock is brutal on tires and boots. If you're hiking around SP Crater or Sunset Crater, wear thick-soled boots. The cinders are basically like walking on ball bearings, and the basalt is sharp enough to cut skin.

Check the weather. These volcanic fields are at high altitudes. While Phoenix is baking at 110 degrees, the San Francisco Volcanic Field might be in the 70s—or covered in snow.

Respect the land. Many of these sites are culturally sensitive. Stay on marked trails, especially at Sunset Crater. The "cinder" surface is incredibly fragile. One footprint can last for decades, and it speeds up erosion that ruins the natural symmetry of the cones.

Download offline maps. Cell service in the Uinkaret or the deeper parts of the San Bernardino field is non-existent. Use an app like Gaia GPS or AllTrails and download the topographical layers before you leave the house.

Visit the Museum of Northern Arizona. Located in Flagstaff, they have incredible exhibits that explain the "how" and "why" of the volcanoes you’re about to see. It’s the best way to get your bearings before heading into the field.

Arizona's volcanic story is still being written. The heat is still down there. The crust is still thin. And while we might be in a quiet period, the map reminds us that the desert is anything but dead. It’s just waiting for its next moment to reshape the world.