It is arguably the most famous photograph of the 20th century. You’ve seen it on posters, in history textbooks, and splashed across social media every August. A sailor in a dark uniform grips a woman in a white nurse’s outfit, bending her back in a dramatic, cinematic arch while they kiss in the middle of a crowded New York City street. It feels like the ultimate "happily ever after" for a world exhausted by years of global slaughter. But if you look closer at the VJ Day in Times Square photo, the reality is way messier, a lot less romantic, and arguably darker than the postcard version suggests.

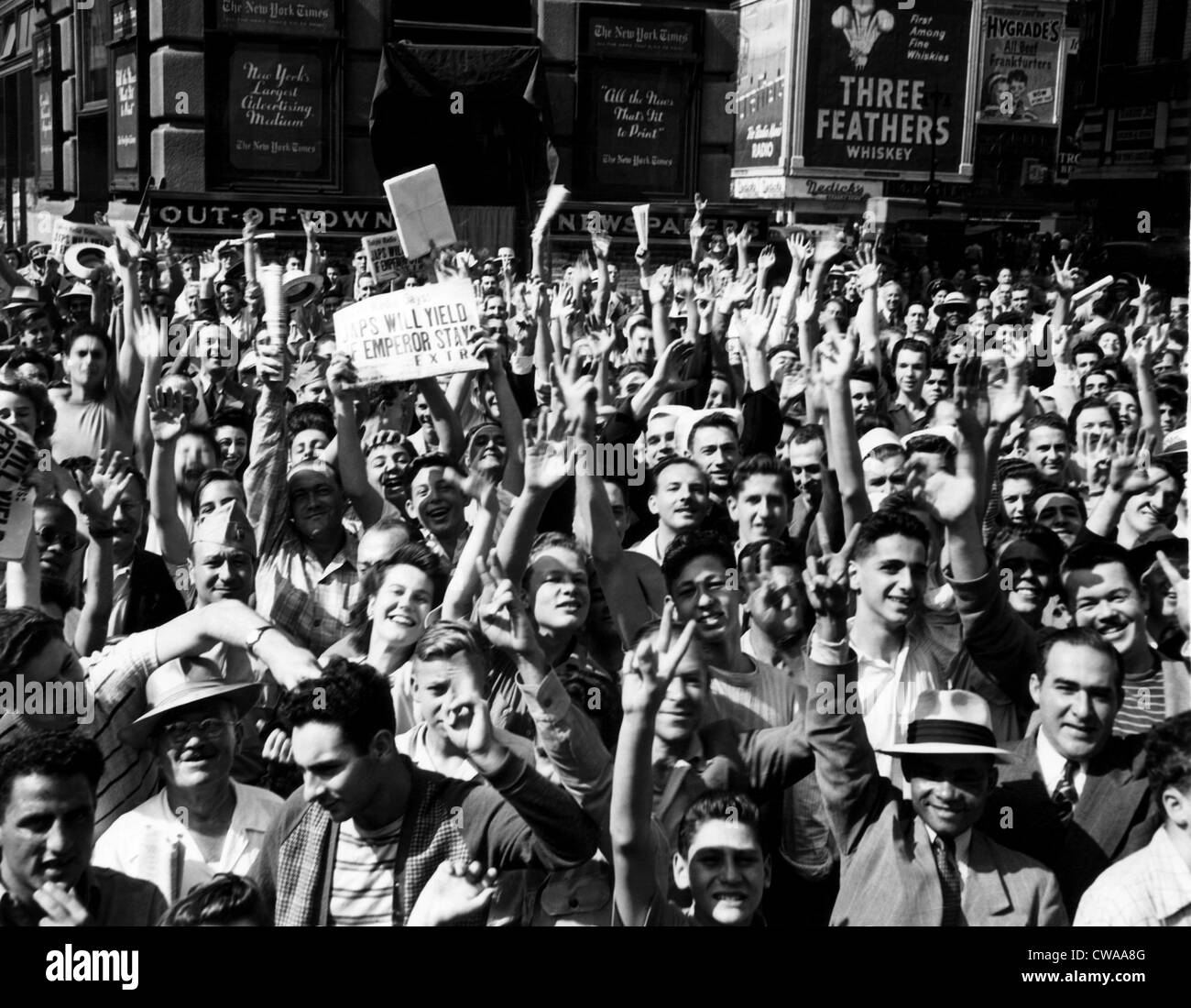

The world stopped on August 14, 1945. When President Harry S. Truman announced the surrender of Japan, Manhattan basically exploded. Roughly two million people crammed into Times Square. It was chaos. People were climbing lampposts, crying, and, as the camera captured, grabbing anyone within arm's reach.

Alfred Eisenstaedt, a photographer for Life magazine, was there with his Leica. He wasn't setting up a shoot. He was hunting. He saw a flash of white and a blur of blue. He clicked the shutter four times in a matter of seconds. He didn't even get their names. For decades, that lack of information fueled a massive mystery that turned the VJ Day in Times Square photo into a historical Rorschach test.

👉 See also: Television Stations in West Palm Beach Florida: What Most People Get Wrong

Who Were They, Actually?

For years, dozens of men and women claimed to be the "kissers." It became a weird sort of 15 minutes of fame. Some were looking for a paycheck; others genuinely believed it was them in the fog of a drunken, celebratory war-end haze.

Eventually, the "nurse" was identified as Greta Zimmer Friedman. Here’s the kicker: she wasn't a nurse. She was a dental assistant. She had just stepped out of her office on Lexington Avenue to see if the rumors of the war's end were true. She wandered into Times Square and, within moments, was grabbed by a stranger. She later said she didn't see him coming. It wasn't a choice.

The sailor was George Mendonsa. He was on leave, having survived the horrors of the Pacific theater. Specifically, he had been on the USS The Sullivans during the Battle of Okinawa, where he watched planes hit the USS Bunker Hill and spent hours pulling scorched sailors from the water. On August 14, he was on a date with another woman—Rita Petry—at Radio City Music Hall. When the news broke, they headed to a bar, George got pretty hammered, and they spilled out into the street.

The Third Person in the Frame

If you look at the uncropped version of the VJ Day in Times Square photo, or the other shots Eisenstaedt took, you can see a woman smiling just over George’s right shoulder. That’s Rita. His actual date. His future wife. She’s right there, watching her boyfriend grab a complete stranger and plant one on her.

Honestly, it’s a bizarre detail that most people gloss over. Rita and George stayed married for seven decades until his death in 2019. She reportedly didn't mind the kiss, or at least she made peace with it, citing the sheer insanity of the day. But for modern viewers, this detail changes the vibe from "true love" to "victory-induced mania."

The Consent Debate and Why it Matters Now

We have to talk about the elephant in the room. In the last ten or fifteen years, the way we look at the VJ Day in Times Square photo has shifted dramatically.

In the 1940s and 50s, this was seen as a symbol of liberation. Today, many people see it and think: Wait, that’s an assault. Greta herself said in an interview with the Veterans History Project in 2005, "It wasn't my choice to be kissed. The guy just came over and grabbed!" She noted that he was incredibly strong. He was holding her so she couldn't move.

Is it fair to judge a 1945 moment by 2026 standards? That’s the debate that keeps this photo in the news cycle every year. Some historians argue that the context of "the world just stopped ending" excuses the behavior. Others argue that celebrating a forced kiss as the "pinnacle of American romance" sends a terrible message about bodily autonomy.

Greta never held a grudge against George. She viewed it as an act of jubilation, not a sexual one. But the visual of her pinned arm and her clenched fist—which you can see if you zoom in—tells a story of surprise and lack of agency that the "romantic" filter usually hides.

Technical Brilliance or Just Lucky?

Eisenstaedt wasn't the only one who got the shot. Victor Jorgensen, a Navy photojournalist, took a photo of the same moment from a different angle. His photo, titled Kissing the War Goodbye, is often confused with Eisenstaedt’s, but it’s shot from the side, lacks the scale of Times Square, and is in the public domain.

Eisenstaedt’s version is better. Period.

Why? Because of the contrast. He specifically mentioned that if Greta had been wearing dark clothes, he wouldn't have taken the picture. The "V" shape of the bodies, the stark white of her uniform against his dark navy wool, and the leading lines of the buildings behind them create a perfect composition. He was shooting with a Leica IIIa, a tiny camera by the standards of the day. It allowed him to be invisible. He wasn't a guy with a giant press camera and a flashbulb; he was a fly on the wall.

He didn't have time to check his settings. He just saw the contrast and reacted. That’s the difference between a snapshot and an icon.

The Hunt for the "Real" Sailor

The search for the identities was a decades-long saga. Life magazine didn't even try to find them until 1980. They put out a call, and eleven men and three women stepped forward.

🔗 Read more: Adolf Hitler Brothers and Sisters: The Tragic Reality of the Family He Outlived

George Mendonsa eventually used forensic face-mapping and bone-structure analysis to prove it was him. A volunteer at the Naval War College, Captain Edward Lawrence, used "photogrammetry" to analyze the shadows and the scars on the sailor's hands to confirm George was the guy.

There was another prominent claimant, Glenn McDuffie. He even passed polygraph tests. But the physical evidence—the bump on the wrist, the specific growth pattern of the hair—eventually pointed toward Mendonsa. It’s funny how much scientific effort has been poured into a three-second interaction between two people who didn't even know each other's names.

The Cultural Legacy

This image has been parodied in The Simpsons, recreated in statues, and used in countless advertisements. There’s a massive statue of it in Sarasota, Florida, called "Unconditional Surrender." It’s controversial. People have spray-painted "#MeToo" on it.

It’s a polarizing piece of art because it represents two things at once:

- The end of a war that killed 70 to 85 million people.

- A moment where a woman’s space was invaded for the sake of a man's celebration.

Both things are true. You don't have to pick one. That complexity is actually why the photo hasn't faded away. If it were just a boring, staged photo of a couple, we wouldn't still be talking about it eighty years later. We talk about it because it’s a "raw" moment. It’s human. It’s messy. It’s the sound of a giant sigh of relief captured on film.

✨ Don't miss: Winter Storm Watch Issued for Maryland Starting Tuesday: What You Actually Need to Know

Surprising Facts You Probably Didn't Know

- The Clock: You can see a clock in the background of some versions of the shot. It was 5:51 PM.

- The Uniform: Greta wasn't a nurse, but she wore the white uniform because that was the standard for dental assistants at the time. This "mistaken identity" contributed to the photo's status as a tribute to the medical profession.

- The Aftermath: George and Greta didn't see each other again until 1980. They didn't become friends, though they were cordial. They lived entirely separate lives.

- The Date: August 14 is often called V-J Day, but the formal signing of the surrender didn't happen until September 2 on the USS Missouri. The photo captures the announcement, not the formal ceremony.

How to View the Photo Today

If you want to see the original prints, they are scattered in museums like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. But honestly, the best way to "experience" the photo is to look at the contact sheet. Seeing the frames right before and right after shows you how fast it happened. It shows the sailor stumbling through the crowd. It shows the nurse walking away immediately after.

It wasn't a lingering embrace. It was a collision.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're interested in the history of photojournalism or the end of WWII, here is what you should do next to get the full picture:

- Look up Victor Jorgensen’s angle: Compare Kissing the War Goodbye with Eisenstaedt’s version. It teaches you a lot about how "framing" changes the emotion of a scene.

- Read the 2005 Library of Congress interview: Greta Zimmer Friedman tells the story in her own words. It’s much more grounded and less "glamorous" than the legend suggests.

- Visit the Paley Center or similar archives: Look for the newsreel footage of Times Square on August 14, 1945. Seeing the sea of people moving in real-time makes the photo feel less like a statue and more like a heartbeat.

- Research the USS The Sullivans: Understanding George Mendonsa’s trauma from the Pacific theater doesn't excuse the grab, but it provides essential context for why he was acting like a man possessed when the war finally ended.

The VJ Day in Times Square photo is more than just a picture of a kiss. It’s a document of a world exhaling. Whether you see it as a beautiful moment or a problematic one, it remains the definitive visual period at the end of the most violent sentence in human history.