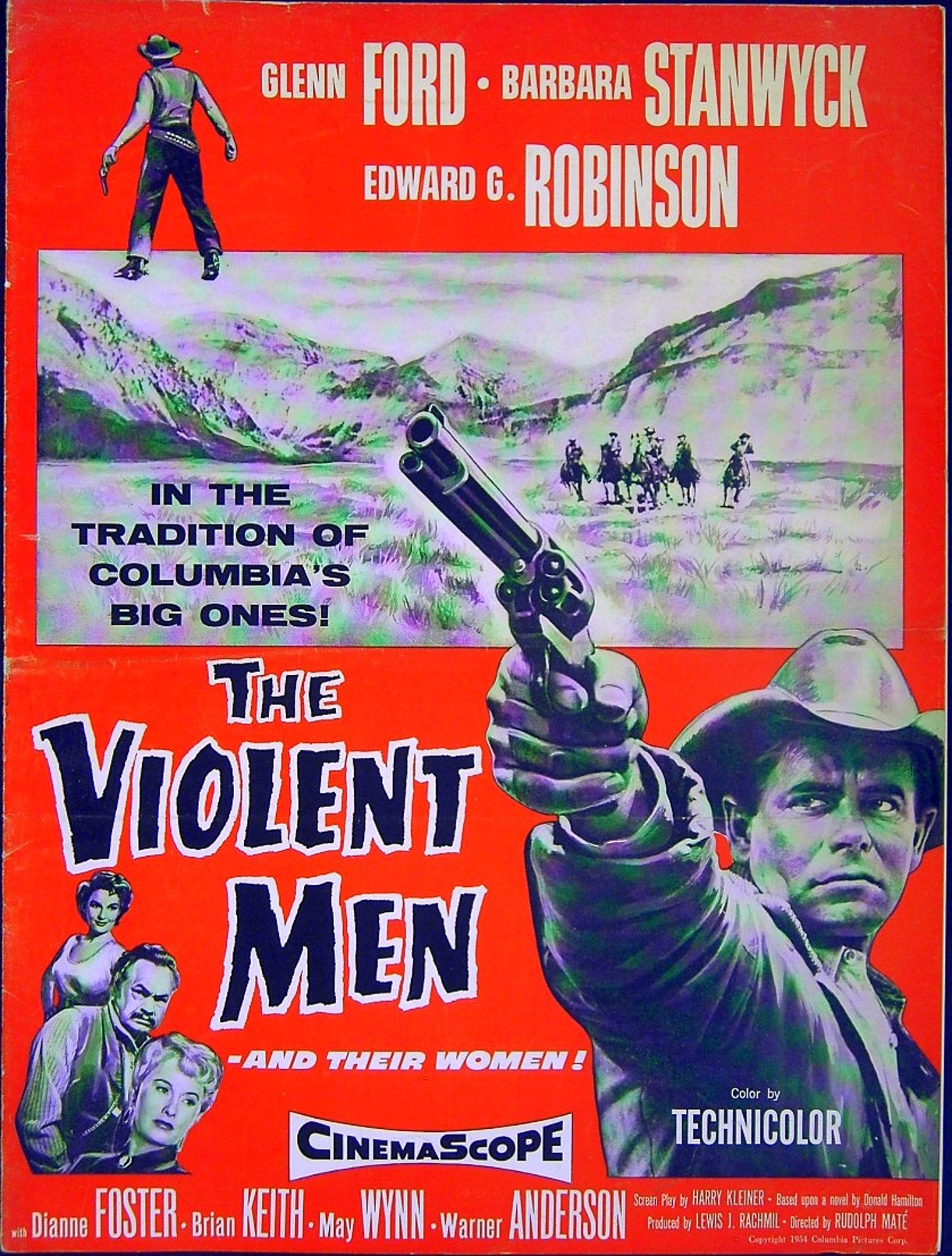

It is dusty. It is surprisingly mean. And honestly, it is way better than a standard mid-century Western has any right to be. We’re talking about The Violent Men, the 1955 CinemaScope epic that basically paved the way for the "hard" Westerns of the sixties and seventies. If you’ve ever watched a movie where a massive cattle rancher tries to steamroll everyone in his path, you’ve seen the DNA of this film. But most people haven't actually sat down to watch the original source of that tension.

John Parrish, played by Glenn Ford, just wants to sell his land and leave. He’s a former Union officer, he’s tired of fighting, and he’s got a girl waiting for him back East. Simple, right? Wrong.

Enter Lew Wilkison. Edward G. Robinson plays him with this weary, menacing gravitas that makes your skin crawl. He’s a crippled land baron who thinks he owns the entire valley. He doesn't just want the land; he wants the world to bow to him. It’s a classic setup, but the execution is where things get gritty.

The Psychological Warfare of Anchor Ranch

Most Westerns of the fifties were about "good guys" in white hats and "bad guys" in black hats. The Violent Men isn't interested in that. It’s interested in how pressure breaks people.

Lew Wilkison isn't even the most dangerous person in his own house. That title probably goes to his wife, Martha, played by Barbara Stanwyck. If you know Stanwyck from Double Indemnity, you know exactly the kind of cold-blooded energy she brings here. She’s manipulating her husband, she’s having an affair with his younger brother, and she’s the one truly driving the violence.

The movie isn't just about gunfights. It’s about the slow-motion car crash of a family destroying itself while trying to build an empire. You’ve got the brother, Cole, who is basically a sociopath with a holster. He’s played by Brian Keith, and he makes every scene feel like a powder keg.

Why does this matter? Because it treats the Western genre as a Greek tragedy. The sweeping shots of the Lone Pine landscape aren't just for show. They emphasize how small these people are compared to the land they’re killing each other over.

Why the Cinematography Actually Changed Things

Director Rudolph Maté was a cinematographer first. He shot Gilda. He knew how to make a frame look expensive. In The Violent Men, he uses the wide CinemaScope lens to create a sense of isolation. Even when characters are in the same room, they feel miles apart.

💡 You might also like: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

There's this one specific scene where the Wilkison riders burn down a neighbor's house. It isn't filmed like a heroic action beat. It feels chaotic and cruel. You see the smoke billowing against the mountains, and you realize Parrish can't just "stay out of it." Neutrality is a luxury he can't afford.

The Turning Point: When John Parrish Stops Being Polite

Glenn Ford was the king of the "quiet man who snaps."

For the first half of the film, Parrish is almost annoying in his pacifism. He takes insults. He lets people walk over him. He’s trying to be the bigger man. But the movie argues that in a lawless land, being the bigger man just gets you buried.

When he finally decides to fight back, it isn't a clean, honorable duel. It’s a guerrilla war. He uses his military training to pick off the Wilkison riders one by one. It’s calculated. It’s cold. Honestly, it’s a little terrifying to see the shift in his eyes.

This is the "violent man" the title refers to. It’s not just the villains. It’s the hero who discovers he’s just as capable of brutality as the people he hates.

Realism vs. Hollywood Glamour

In 1955, most movies were still sanitized by the Hays Code. You couldn't show too much blood. You couldn't show too much "sin."

Yet, The Violent Men pushes those boundaries. The implication of Martha and Cole’s affair was scandalous for the time. The way they treat Lew—a man who can't walk—is genuinely uncomfortable to watch. It’s a movie that acknowledges people are often motivated by greed and lust rather than some high-minded sense of destiny.

📖 Related: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

The screenplay was based on a novel called Night of the Wild Horses by Donald Hamilton. Hamilton also wrote the Matt Helm spy novels, and you can see that gritty, procedural edge in the way the plot unfolds. It’s tight. It doesn't waste time on subplots that don't matter.

What Most People Get Wrong About 50s Westerns

If you think all old Westerns are boring or "safe," this is the movie that proves you wrong. People often lump it in with the cheesy B-movies of the era, but that’s a mistake.

- It’s not a black-and-white morality tale. Every character has a reason for their madness. Lew Wilkison wants a legacy because he feels his body failing him. Martha wants power because she’s spent her life in the shadow of men.

- The pacing is surprisingly modern. It doesn't meander. Once the first house burns, the momentum never stops.

- The female characters have agency. Stanwyck isn't a damsel. She’s the architect of the chaos. She’s the smartest person in the room, even if her morals are non-existent.

The Influence on Modern Television

Think about shows like Yellowstone or Succession.

The core of those stories is a powerful, aging patriarch whose empire is crumbling from the inside because of his own family’s greed. That is exactly what’s happening in The Violent Men. It’s the blueprint for the modern "prestige" drama.

When you see a modern anti-hero finally lose their temper and resort to violence, you’re seeing the ghost of Glenn Ford’s performance. He showed that you don't have to be a loud-mouth to be dangerous. The quietest guy in the room is usually the one with the highest body count.

Why You Should Watch It Right Now

If you're a film buff, you need to see this for the technical skill alone. The lighting, the use of color, and the sheer scale of the production are top-tier.

But if you just want a good story, watch it for the tension. It’s one of those rare films where you genuinely don't know who is going to survive the final act. It avoids the "perfect" ending where everyone gets what they deserve. Instead, it leaves you with a bit of a bitter taste, which is exactly how a story about the "violent men" of the West should end.

👉 See also: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

Actionable Insights for the Modern Viewer:

- Watch for the subtext: Pay attention to how Barbara Stanwyck uses her voice. She rarely shouts, but she commands every frame.

- Compare the landscapes: Look at how the cinematography changes when the action moves from the open valley to the cramped interiors of the ranch house. It’s a lesson in visual storytelling.

- Track the change in Glenn Ford: Note the exact moment his character stops being a "rancher" and starts being a "soldier" again. It’s a subtle shift in his posture and the way he wears his hat.

- Check out the source material: If you like the movie, find Donald Hamilton’s original writing. He’s one of the masters of the "hard-boiled" Western.

The West wasn't won by nice people. It was carved out by people who were willing to do things they could never take back. This film understands that better than almost any other movie of its time. It’s a masterclass in tension, and it deserves a spot on your "must-watch" list if you care about the history of American cinema.

Find a high-definition restoration if you can. The CinemaScope visuals lose a lot of their power on a low-res stream or a cropped 4:3 version. You need the full width of the screen to feel the emptiness of the valley and the weight of the mountains pressing down on these characters.

The next time someone tells you old movies are "slow," put this on. By the time the third act hits, they'll be glued to the screen.

Steps to Deepen Your Appreciation:

- Research the filming locations in Lone Pine, California. Many of the rock formations are still recognizable today and have been used in hundreds of films.

- Listen to the score by Max Steiner. He’s the same guy who did Gone with the Wind, and you can hear that classic Hollywood orchestral power throughout.

- Look up the career of Rudolph Maté. Understanding his background as a cinematographer helps explain why the movie looks so much more sophisticated than other Westerns from 1955.

This isn't just a movie about cowboys. It’s a study of power, betrayal, and the cost of survival. It holds up because the human elements—greed, love, and the desire for peace—never go out of style.