It looks like a giant, shattered porcelain plate floating in a dark bathtub. That is usually the first reaction when people see the view of Antarctica from space for the real, unedited first time. We are conditioned by school globes and flat Mercator maps to think of it as a tidy strip of white at the bottom of the world. It isn't. It’s a massive, pulsating, topographical monster that holds about 90% of the world's ice and 70% of our fresh water.

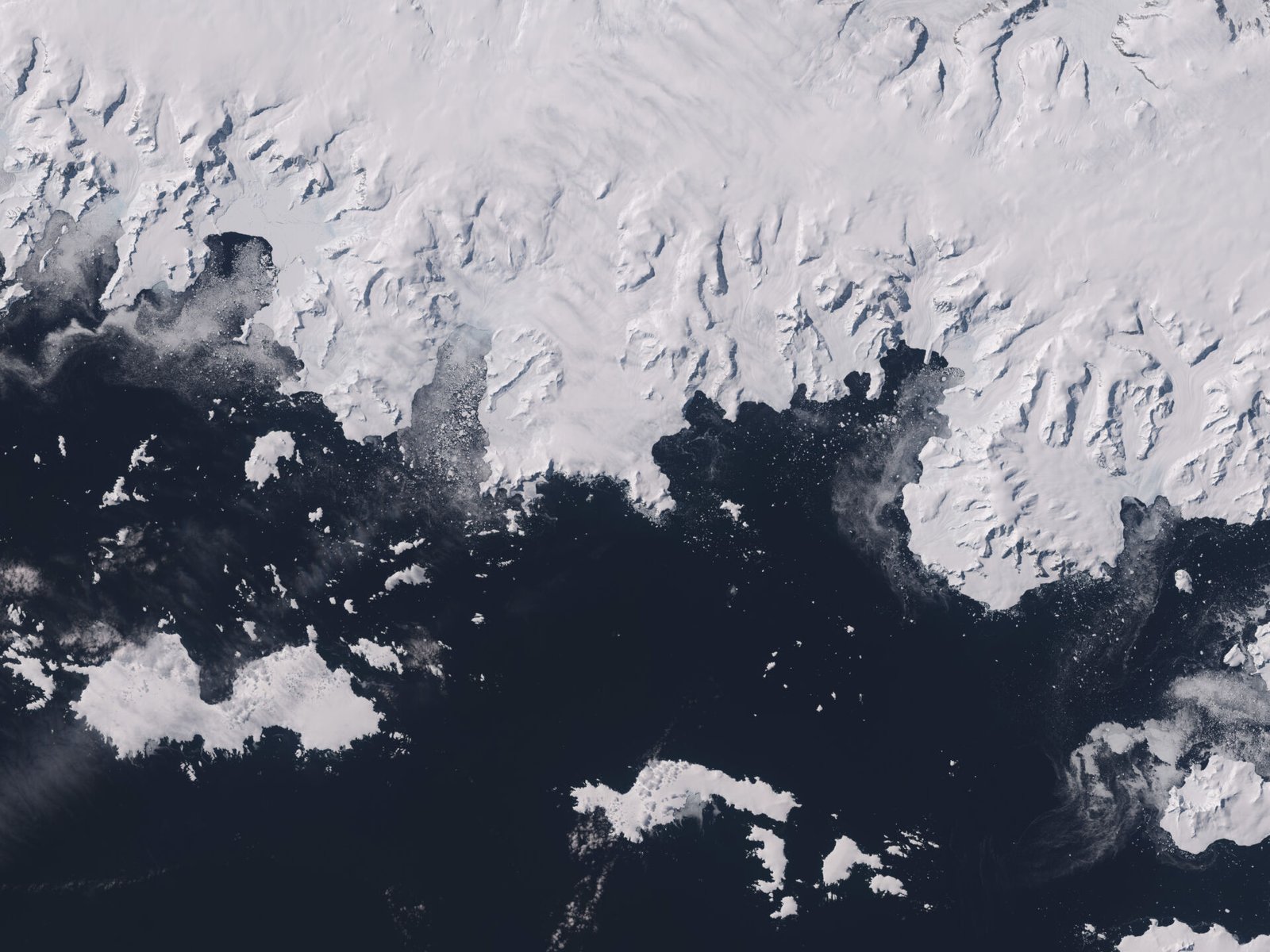

Seeing it from 250 miles up—the altitude of the International Space Station (ISS)—changes your perspective on how "solid" the Earth actually is. From that height, you don't just see white. You see deep cerulean cracks, shadows cast by mountains taller than the Alps that are completely buried in snow, and the terrifyingly beautiful swirl of the Southern Ocean. Honestly, it’s the most alien place on our own planet.

Why the view of Antarctica from space looks so different than you’d expect

Most people think the satellite view is just a static white blob. It’s not. If you look at high-resolution imagery from NASA’s Landsat 8 or the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2, you realize the continent is alive.

The color palette is surprisingly diverse. You have "blue ice" areas where the wind has stripped away the snow, revealing ancient, compressed ice that looks like glass. Then there are the nunataks. These are jagged mountain peaks poking through the ice sheet like the spine of a buried dragon. From space, these look like black ink dots on a white canvas. They are the only parts of the continent's interior that aren't buried under miles of frozen water.

NASA’s Christopher Shuman, a glaciologist, often points out that we aren't just looking at a landscape; we are looking at a dynamic engine. The ice is constantly moving from the center of the continent out toward the sea. When you zoom in on the view of Antarctica from space, you see the flow lines. They look like frozen rivers. Because that’s exactly what they are. The Pine Island Glacier and the Thwaites Glacier—the so-called "Doomsday Glacier"—look like massive, slow-motion highways of ice grinding their way into the Amundsen Sea.

The Blue Marble vs. The Reality

Remember the famous "Blue Marble" photo from Apollo 17? It’s arguably the most famous view of the white continent. But that was a lucky shot. Antarctica is usually shrouded in a swirling vortex of clouds. The Southern Ocean is one of the cloudiest places on Earth. Getting a clear, cloud-free shot of the entire continent is actually incredibly difficult. Scientists often have to stitch together thousands of different satellite passes over months to get a "clean" mosaic.

When you do get that clear view, the scale is haunting. Antarctica is bigger than the United States and Mexico combined. Think about that. A desert of ice larger than North America, and from space, you can see the wind-carved patterns, called sastrugi, which can be feet tall but look like tiny ripples from orbit.

The technology making the invisible visible

We used to rely on simple optical cameras. If it was cloudy, we saw nothing. If it was the six-month-long polar night, we saw nothing. That’s changed. Now, we have Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR).

SAR is basically a cheat code for the view of Antarctica from space. It sends microwave pulses down to the surface that can "see" through clouds and through the dark of winter. This is how we discovered that Antarctica isn't just a solid block of ice sitting on a rock. It’s actually sitting on a complex network of liquid lakes.

Take Lake Vostok. It’s a subglacial lake the size of Lake Ontario, buried under two miles of ice. We can’t "see" it with our eyes from space, but satellite altimetry (measuring the height of the ice surface) shows a perfectly flat, level "plateau" where the ice is floating on the water of the lake beneath it. It’s wild. You’re looking at a map of a hidden world.

ICESat-2 and the laser show

NASA’s ICESat-2 is another beast entirely. It fires a laser at the ice 10,000 times a second. It measures the height of the ice down to the width of a pencil. When we look at the data visualizations from this satellite, we see the continent breathing. We see the ice shelves—the floating tongues of ice—rising and falling with the tides of the ocean underneath them.

You’ve probably heard of the massive icebergs breaking off, like A-68 or the more recent A-81. From space, these look like small shards of glass. In reality, A-68 was the size of Delaware. Watching these from a satellite perspective is like watching a very slow, very high-stakes game of Tetris as they navigate the "Iceberg Alley" toward the South Atlantic.

The "Hole" in the sky

You can't talk about the view of Antarctica from space without mentioning the ozone hole. It’s not actually a hole where the atmosphere is missing, but a massive thinning of the ozone layer in the stratosphere.

Satellite instruments like the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on the Aura satellite give us a "view" of this chemical phenomenon. It usually shows up in visualizations as a purple or deep blue bruise over the continent. It fluctuates. It grows in the spring (September/October) and shrinks in the winter. Seeing this from space was the smoking gun that led to the Montreal Protocol. It was the first time humanity saw the direct, visible impact of our chemicals on the planet's "skin" from a God's-eye view.

Life at the edge of the world

Can you see life from space? Usually, no. Antarctica is too big, and penguins are too small. But scientists found a workaround: poop.

Specifically, penguin guano. Emperor penguin colonies are large, and their waste stains the white ice a reddish-brown color. From space, these stains are visible even when the penguins themselves are not. In fact, several new colonies of Emperor penguins have been discovered purely by scanning the view of Antarctica from space for brown spots. It's a low-tech biological marker detected by high-tech orbital sensors.

Then there are the research stations. McMurdo Station, the largest "city" on the continent, looks like a tiny gray smudge on the edge of Ross Island. During the winter, it’s a literal lighthouse. Astronauts on the ISS have occasionally spotted the faint glow of human activity in the vast, terrifying darkness of the Antarctic night. It’s a reminder of how small we are.

What it feels like for the astronauts

Most astronauts describe the Antarctic view as "pure." While the rest of the world is a patchwork of cities, roads, and brown smog, Antarctica is a blinding, pristine white. But it’s also a warning.

👉 See also: Facebook Marketplace Venmo Scams: What Most People Get Wrong

When you look at the Larsen C ice shelf from orbit, you see the cracks. These aren't just little lines; they are miles wide. You see the melt ponds—vibrant, sapphire-blue pools of water sitting on top of the white ice. They look beautiful, like jewels. But to a scientist, they are a bad omen. They act like wedges, forcing the cracks deeper and causing the shelves to shatter.

Basically, the view from space shows us a continent that is losing its armor.

Actionable Insights: How to explore the view yourself

You don't need a billion-dollar budget or a ride on a Soyuz rocket to see this. The data is largely public. If you want to see the "real" Antarctica as it looks right now, here is how you do it:

- NASA Worldview: This is the best tool, period. It’s a web interface where you can overlay daily satellite imagery. You can toggle between "True Color" (what you'd see with your eyes) and "Bands 7-2-1," which makes ice look bright red or electric blue to distinguish it from clouds.

- Google Earth Engine: If you’re a bit more tech-savvy, you can use this to see time-lapses of the Antarctic coastline. Watching the ice shelves retreat over 40 years is a sobering experience.

- The LIMA Map: The Landsat Image Mosaic of Antarctica (LIMA) is the most detailed high-resolution map ever created. It’s a "seamless" view that lets you zoom in on individual mountain ranges and glacier tongues.

- Check the "Iceberg Tracking" sites: The US National Ice Center (USNIC) keeps a running list of all named icebergs. You can find their coordinates and then plug them into NASA Worldview to see where a mountain-sized piece of ice is currently drifting.

Watching the view of Antarctica from space isn't just about pretty pictures. It’s about monitoring the heartbeat of the world's climate. The continent is the ultimate "canary in the coal mine." When the view changes—when the white turns to blue or the edges start to crumble—the rest of the world feels it through rising sea levels and shifting weather patterns.

Keep an eye on the Ross Ice Shelf. It’s the size of France. If that ever starts to look "unstable" from your laptop screen, the world is in for a very different future. The view from above is our best way to prepare for what’s coming below.

Next Steps for Exploration

To truly grasp the scale of what you're seeing, start by locating McMurdo Station on Google Earth (77.8419° S, 166.6863° E). Once you find that tiny human footprint, zoom out slowly. Watch as the buildings disappear, then the island, then the entire coastline, until you are looking at the massive, silent expanse of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Compare this view to the imagery from the 1990s using the historical imagery tool. You will notice that while the center remains seemingly eternal, the edges are fraying in real-time. This visual audit is the most direct way to understand the physical reality of our changing planet without reading a single academic paper.