You probably think about your heart as a pump. That’s fair. It is. But a pump is useless if the fluid has no way to get back to the start of the line. Enter the vena cava. Without these two massive vessels, your oxygen-depleted blood would just... sit there in your toes or your brain. Your heart would be pumping nothing but air.

Actually, it’s more accurate to say the vena cava is the "highway system" for every drop of blood that has already finished its job delivering oxygen to your cells. It’s dark, it’s deoxygenated, and it’s under surprisingly low pressure.

Most people focus on the aorta. The aorta is the flashy one, the high-pressure garden hose spraying fresh blood to the body. But the vena cava is the quiet workhorse. If the aorta is the "delivery truck," the vena cava is the entire global logistics network bringing the empty crates back to the warehouse for a refill. It's huge. It's essential. And honestly, it’s often where the most interesting medical mysteries happen.

So, What Exactly is the Vena Cava?

Basically, the vena cava is the largest vein in the human body. It isn’t just one single tube, though. It’s split into two distinct parts: the superior vena cava (SVC) and the inferior vena cava (IVC). They both dump into the right atrium of the heart, but they cover very different territories.

Think of the SVC as the "Upper Management." It handles everything from the chest up—your head, neck, arms, and upper chest. The IVC is the "Field Operations." It’s much longer and carries blood from your legs, feet, and everything in your abdomen. Because gravity is a thing, the IVC has a much harder job. It has to haul blood all the way from your ankles back up to your chest against the constant pull of the earth.

Veins are different from arteries. Arteries have thick, muscular walls to handle the "thump-thump" of the heart's pressure. The vena cava is different. Its walls are thinner. It’s more of a floppy, high-capacity conduit. Because the pressure is so low, your body relies on other things—like the movement of your leg muscles and the vacuum created when you breathe—to keep that blood moving north.

✨ Don't miss: Bragg Organic Raw Apple Cider Vinegar: Why That Cloudy Stuff in the Bottle Actually Matters

The Superior Vena Cava: The Fast Lane from the Brain

The SVC starts where the left and right brachiocephalic veins join up. It’s only about 7 centimeters long. Short. Efficient. It’s tucked away in the upper right part of your chest. If this gets compressed—maybe by a tumor in the lung or a swollen lymph node—you get something called SVC Syndrome. Your face swells. Your neck veins bulge. It’s a medical emergency because that blood has nowhere else to go.

The Inferior Vena Cava: The Long Haul

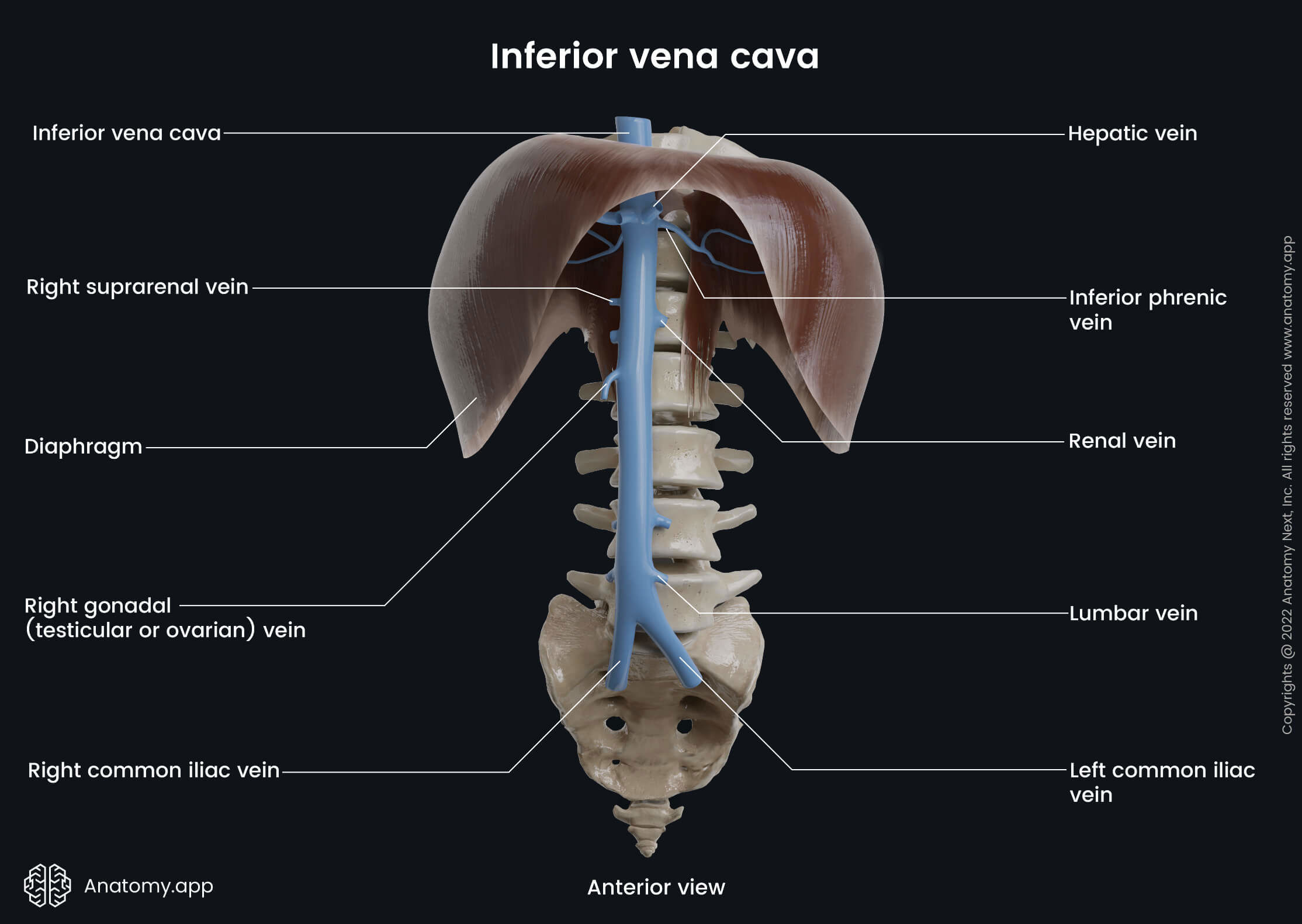

The IVC is the heavyweight champion. It begins in the lower back where the common iliac veins meet and travels all the way up the right side of the spine. It passes through the diaphragm through its own dedicated hole (the caval opening) before hitting the heart. Along the way, it picks up blood from the liver via the hepatic veins and from the kidneys via the renal veins.

Why the Pressure Matters (and Why It’s So Low)

Physics is weird when it comes to the vena cava. In the aorta, your blood pressure might be 120 mmHg. In the vena cava? It’s often near zero. Sometimes, it’s even negative when you take a deep breath.

This is vital. If the pressure in the vena cava were high, the blood couldn't flow into the heart easily. The heart needs that pressure gradient—the difference between "high" and "low"—to function. But this low pressure makes the IVC vulnerable. If you are pregnant, for instance, the weight of the baby can literally squash the IVC against your spine when you lie on your back. Doctors call this "Supine Hypotensive Syndrome." It’s why pregnant women are told to sleep on their left side. By shifting the weight off the vena cava, the blood can actually get back to the heart, preventing dizziness or a drop in blood pressure.

Real-World Risks: Blood Clots and Filters

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) is a term you’ve probably heard on long flights or in hospital commercials. If a clot forms in your leg, it’s a problem. But the real danger is if that clot breaks loose.

🔗 Read more: Beard transplant before and after photos: Why they don't always tell the whole story

Where does it go? It hitches a ride up the inferior vena cava.

Since the IVC gets wider as it goes up, the clot moves easily until it hits the heart and gets pumped into the lungs. That’s a pulmonary embolism. To stop this, surgeons sometimes insert an "IVC Filter." It’s a tiny, umbrella-shaped device made of metal (usually nitinol) that sits inside the vena cava. It acts like a literal strainer, catching clots before they can reach the heart.

However, medical experts like those at the Mayo Clinic have noted that these filters aren't permanent fixes. They can occasionally migrate or even fracture if left in too long. It’s a delicate balance between stopping a clot and introducing a foreign object into the body’s largest pipe.

The Role of the Vena Cava in Modern Surgery

Surgeons use the vena cava as a landmark. During liver transplants or kidney cancer surgeries, the IVC is the "North Star."

Sometimes, kidney tumors (specifically Renal Cell Carcinoma) can actually grow a "tumor thrombus" that crawls up the renal vein and into the IVC. It’s wild. A tumor can literally extend like a finger through the vein, sometimes reaching all the way into the heart. Operating on this requires a massive team—vascular surgeons, urologists, and sometimes cardiac surgeons—because they have to open the vena cava, remove the tumor, and sew the vein back shut without the patient bleeding out. It’s high-stakes medicine.

💡 You might also like: Anal sex and farts: Why it happens and how to handle the awkwardness

Common Misconceptions About Veins

People often think all veins are blue because they see blue lines under their skin. They aren't. Blood in the vena cava is a deep, dark maroon. The blue color is just an optical illusion caused by how light interacts with your skin and fat.

Another myth? That veins are just passive tubes. While they don't "pump" like the heart, the vena cava has a slight ability to constrict or dilate to manage your "preload"—the amount of blood returning to the heart. If you're dehydrated, your vena cava will actually look "flat" on an ultrasound. ER doctors use this trick all the time. They put an ultrasound probe on a patient’s belly to look at the IVC. If it's thin and collapses when the person breathes, they know the patient needs IV fluids. If it's wide and bulging, the heart might be struggling to keep up with the volume.

Actionable Insights for Vascular Health

You can't "exercise" your vena cava directly, but you can help it do its job.

- Keep Moving: Since the IVC relies on your calf muscles to push blood upward, sitting for 10 hours straight is its worst nightmare. Flex your ankles. Walk around.

- Hydration is Key: Low blood volume makes the return trip through the vena cava more sluggish.

- Compression Gear: If you have varicose veins or poor circulation, compression socks provide that extra external pressure the vena cava needs to overcome gravity.

- Sleep Positions: If you have circulation issues or are in the later stages of pregnancy, tilting to the left side keeps the weight of your internal organs off the IVC.

- Watch the Swelling: Unexplained swelling in both legs can be a sign that the vena cava is struggling to return blood to the heart, often due to underlying heart or kidney issues.

The vena cava is the ultimate proof that in the human body, the "return journey" is just as important as the departure. Without this massive plumbing system, the heart is just a pump running dry. Paying attention to leg health, staying active, and understanding the role of venous pressure can literally be a lifesaver.