Biology class lied to you. Well, maybe not lied, but they definitely oversimplified things. When you first heard the definition of a vacuole, your teacher probably called it the "storage bin" of the cell and moved right along to the mitochondria. But honestly? That’s like calling a Swiss Army knife a "piece of metal."

It’s way more than a closet.

Think of a vacuole as a dynamic, membrane-bound organelle that manages everything from waste disposal to structural integrity. It’s basically the reason a wilted plant stands back up after you finally remember to water it. Without these specialized bubbles of fluid, life as we know it—especially plant life—would basically just be a pile of mushy cells with no way to handle their own trash.

So, What is the Actual Definition of a Vacuole?

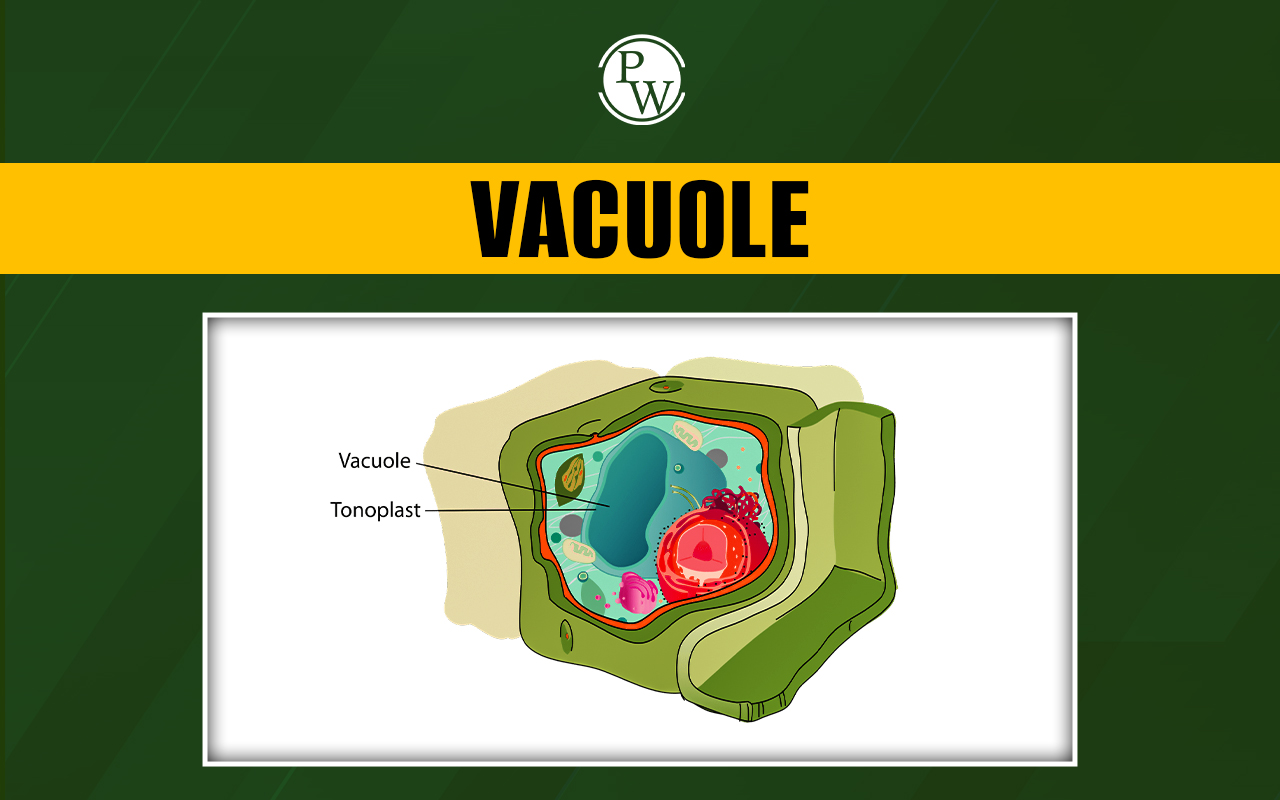

At its most basic level, a vacuole is a space within the cytoplasm of a cell, enclosed by a membrane and typically containing fluid. In the world of cytology, we call that membrane the tonoplast.

It’s empty. But it’s also full.

Wait, that sounds like a Zen koan. What I mean is that while it looks like a clear hole under a microscope, it’s actually packed with a solution called cell sap. This isn't just water; it’s a complex cocktail of enzymes, sugars, mineral salts, and sometimes even pigments that give flowers their color.

In animal cells, vacuoles are small, temporary, and usually involved in scooting things in and out of the cell. But in plants? They are the stars of the show. A mature plant cell often has one massive "Central Vacuole" that can take up 90% of the cell's entire volume. Imagine if your stomach took up 90% of your body. You’d be a walking (or standing) digestive sac.

The Pressure Is On: Turgor and Support

Plants don't have bones. They don't have chitin shells like bugs. So how does a sunflower stay upright?

The answer is turgor pressure.

When a plant is healthy, its vacuole is stuffed with water. This fluid pushes outward against the cell wall. It creates a rigid structure, much like how air makes a balloon firm. When you forget to water your peace lily for three days and it looks like it’s given up on life, that’s because the vacuoles have shrunk. The pressure is gone. The definition of a vacuole in a botanical sense is fundamentally tied to this structural support.

Interestingly, researchers like those at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology have shown that vacuoles are also active players in nutrient signaling. They aren't just sitting there holding water; they are "tasting" the cell's environment and deciding when to release stored nitrates or phosphates back into the cytoplasm.

📖 Related: The Foods to Avoid With Parasites: What Your Gut Really Needs Right Now

Not All Vacuoles Are Created Equal

While we talk about them like a single thing, nature loves to specialize.

- Contractile Vacuoles: Found in funky little organisms like Amoeba or Paramecium. These act like tiny pumps. Because these creatures live in freshwater, water is constantly leaking into them via osmosis. If they didn't have a vacuole to literally spit the water back out, they would explode. No joke. They would just pop.

- Food Vacuoles: These are the cell’s "to-go containers." When a cell engulfs a piece of food through phagocytosis, it wraps it in a membrane. This becomes a temporary stomach where digestive enzymes get to work.

- Sap Vacuoles: This is the classic plant version. They store everything from the toxic chemicals that stop deer from eating the leaves to the beautiful anthocyanin pigments that make blueberries blue.

The Dark Side: Waste and Toxicity

Vacuoles are also the cell's "toxic waste dump." Plants can’t get up and go to the bathroom. They can’t exhale carbon dioxide and call it a day. Instead, they often take metabolic byproducts—things that might be poisonous to the rest of the cell—and lock them away inside the vacuole.

Sometimes, they store "secondary metabolites." These are chemicals that don't help the plant grow but do help it not die. Think of the caffeine in a coffee bean or the nicotine in tobacco. To the plant, these are defense mechanisms stored in the vacuole to mess with the nervous systems of anything trying to eat them. Humans just happened to find them "refreshing."

Christian de Duve, the Nobel Prize-winning cytologist who discovered lysosomes, famously pointed out the similarities between the two organelles. In many fungi and yeast, the vacuole basically is the lysosome, filled with acidic enzymes that tear old proteins apart so the cell can recycle the parts. It’s the ultimate "reduce, reuse, recycle" program.

Why Should You Care? (Beyond the Biology Test)

It feels academic, right? But the definition of a vacuole actually impacts your daily life in weird ways.

Ever wonder why a crisp apple has that "crunch"? That’s the sound of millions of tiny vacuoles bursting and releasing their pressurized fluid as your teeth break the cell walls. If the vacuoles are limp, the apple is "mealy."

In the medical world, understanding how vacuoles function is becoming a huge deal for treating certain diseases. There are "vacuolar diseases" where the pumps that move ions in and out of the membrane fail. This can lead to issues in humans like Danon disease, which affects the heart and muscles because the "trash" isn't being moved out of the cells properly.

Moving Toward Molecular Precision

We are getting better at seeing these things. New imaging techniques, like Cryo-Electron Microscopy, allow us to see the proteins embedded in the tonoplast membrane in real-time. We used to think the membrane was just a fence. Now we know it's more like a high-tech border crossing with thousands of specialized gates (transporters) checking IDs on every molecule that wants to enter.

There’s also the matter of seed longevity. Seeds can sit in a desert for decades without dying. How? Their vacuoles transform into "protein bodies." They harden and stabilize the cell's interior, protecting the machinery of life until the first drop of rain arrives.

It’s sophisticated engineering happening inside a space so small you can’t see it without a lens.

Actionable Steps for Further Exploration

To truly wrap your head around how these organelles function in the real world, try these observations:

- The Wilt Test: Take a wilted stalk of celery and put it in a glass of dyed water (blue food coloring works best). Watch how the "vacuole definition" comes to life as the cells regain turgidity and the dye travels to the storage centers.

- Microscopic Sourcing: if you have access to a basic lab microscope, look at an Elodea leaf. You can actually see the chloroplasts being pushed to the very edges of the cell because the central vacuole is so massive and clear in the middle.

- Study Osmosis: Research how saline soil affects crop yields. When there is too much salt outside a plant, the water leaves the vacuole to balance the salt concentration, causing "physiological drought." This is a major challenge for 2026 global food security.

- Check Protein Storage: Look into how legumes (beans/peas) store nutrients. Their vacuoles are specialized for protein storage, which is why they are such a vital meat alternative in modern diets.