August 1945. Japan was a charred skeleton. Smoke still drifted from the ruins of Tokyo and the radioactive dust of Hiroshima and Nagasaki hadn't even settled yet. When the Americans arrived, everyone expected a bloodbath. They thought the US occupation of Japan would be a brutal, vengeful squeeze. But what actually happened was weirder, more complex, and frankly, more successful than anyone had a right to expect. It wasn't just soldiers marching in; it was a total societal transplant.

General Douglas MacArthur—a man with an ego the size of a small continent—stepped off his plane with a corncob pipe and a plan to rewrite a country’s DNA.

People often think the occupation was just about getting Japan to stop fighting. It wasn't. It was about making sure they never wanted to fight again. That meant changing how they farmed, how they voted, and even how they thought about their "living god" Emperor. You've got to realize that in 1945, the average Japanese citizen had never heard the Emperor's voice until he announced the surrender over the radio. Suddenly, they were seeing Americans handing out chocolate and chewing gum.

The MacArthur Shogun Era

MacArthur became the "Gaijin Shogun." That's not just a cute nickname; it’s basically how he functioned. He understood that to change Japan, he couldn't just destroy the old systems—he had to co-opt them. He kept Emperor Hirohito on the throne, which was a massive gamble. A lot of people in Washington D.C. wanted Hirohito hanged as a war criminal. MacArthur said no. He knew if he killed the Emperor, a guerrilla war would spark that would last decades.

So, they struck a deal. Hirohito stayed, but he had to tell his people he wasn't a god. Imagine believing your leader is a literal deity and then hearing him say on the radio, "Actually, I'm just a guy." That's the level of psychological shock we're talking about during the US occupation of Japan.

The Americans didn't just sit in barracks. They were everywhere. They rewrote the Constitution in about a week. Seriously. A small group of American officials, including a woman named Beate Sirota who insisted on including women's rights, hammered out the "Peace Constitution" in a frantic session. Article 9 is the big one—it says Japan can’t have a military for the purpose of war. It's still one of the most debated pieces of law in the world today.

👉 See also: The Station Nightclub Fire and Great White: Why It’s Still the Hardest Lesson in Rock History

Land, Labor, and Ladies

Before the war, Japan was basically a feudal society disguised as a modern one. A few rich families (the Zaibatsu) owned all the industry, and a few landlords owned all the dirt. The occupation blew that up.

They took land from the rich and sold it to the people actually farming it. It was one of the most successful land reforms in history. If you've ever wondered why Japan has such a robust middle class today, this is where it started. They also gave women the right to vote. In 1946, millions of Japanese women headed to the polls for the first time. It wasn't perfect—social change takes time—but the legal foundation was laid overnight.

The Hunger and the "Pan-pan" Girls

Let's get real for a second. It wasn't all "democracy and sunshine." The early years were desperate. Starvation was a very real threat. You had people trading their family heirlooms, priceless kimonos, and jewelry for a few pounds of sweet potatoes.

This desperation led to the rise of the "Pan-pan" girls—women who worked as sex workers for American GIs just to survive. The black market, or yami-ichi, became the true heart of the economy. If you wanted shoes, medicine, or a decent meal, you didn't go to a store. You went to a bombed-out alleyway and paid three times the price to a guy with connections to the American supply lines.

The US military had a complicated relationship with this. On one hand, they tried to regulate it to prevent disease; on the other, they were the ones fueling the demand. It’s a messy, often ignored part of the history that shows the human cost of the US occupation of Japan.

✨ Don't miss: The Night the Mountain Fell: What Really Happened During the Big Thompson Flood 1976

The Reverse Course: Why the US Changed Its Mind

By 1947, the world was changing. The Cold War was heating up. Suddenly, the US stopped caring so much about "democratizing" Japan and started caring more about making them a "bulwark against communism."

This is what historians call the "Reverse Course."

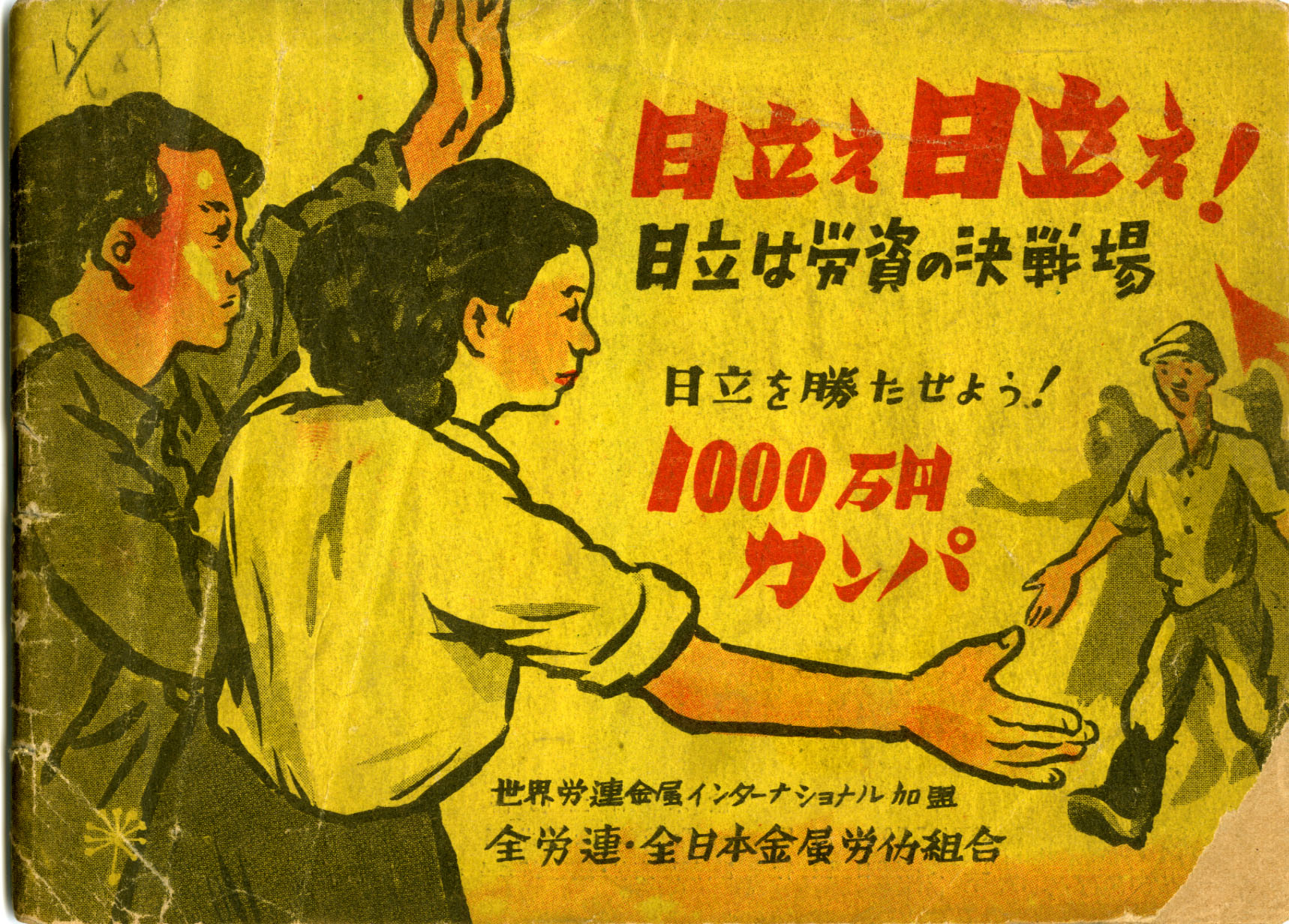

The Americans started cracking down on labor unions they had previously encouraged. They stopped breaking up the big monopolies because they needed Japan’s economy to roar so it wouldn't fall to the Soviets or the Chinese. They even "purged" the communists and brought back some of the old-guard politicians who had been kicked out right after the war.

It was a total 180-degree turn.

Honestly, it’s the reason Japan’s political landscape is so conservative today. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which has ruled Japan for most of the last 70 years, was born out of this era. The US basically paved the road for a one-party-dominant democracy because stability was more important than pure pluralism.

🔗 Read more: The Natascha Kampusch Case: What Really Happened in the Girl in the Cellar True Story

The Culture Shock That Never Left

You can’t talk about this period without talking about the culture. Jazz, baseball, and SPAM.

The Japanese took American influences and "Japanized" them. Baseball was already there, but the occupation turned it into a national obsession. Western fashion became the standard. Even the way people ate changed. The introduction of bread and milk to school lunches—a program started by the US to combat malnutrition—literally changed the physical stature of the next generation of Japanese children. They grew taller than their parents.

But there was also resentment. Having foreign soldiers on your soil for seven years (1945–1952) leaves a mark. Even after the occupation officially ended with the Treaty of San Francisco, the US kept a massive presence in Okinawa. To this day, the tension over US bases in Okinawa is a direct legacy of the occupation.

Why It Worked (And Why It Wouldn't Today)

People often point to the US occupation of Japan as a blueprint for "nation-building" in places like Iraq or Afghanistan. But they usually ignore why it actually worked in Tokyo.

- A Single Authority: MacArthur had near-absolute power. No committees, no bickering—just one guy calling the shots.

- The Emperor Factor: By keeping Hirohito, the Americans had a "shortcut" to legitimacy. When the Emperor said "cooperate," the people cooperated.

- A Homogeneous Society: Japan didn't have the deep sectarian or tribal divides that plague other occupied nations.

- The "Blank Slate" Mentality: The destruction was so total that people were willing to try anything new because the old way had failed them so spectacularly.

Navigating the Legacy Today

If you’re looking to understand the modern world, you have to look at this seven-year window. It’s why Japan is a tech giant, why its constitution is so unique, and why its relationship with the US is so "it's complicated."

Actionable Insights for the History-Curious:

- Visit the Yushukan Museum vs. the Edo-Tokyo Museum: If you're ever in Tokyo, go to both. The Yushukan (at Yasukuni Shrine) gives you the nationalist perspective, while the Edo-Tokyo Museum shows the gritty reality of post-war life. The contrast is eye-opening.

- Read the "Constitution of Japan": It’s surprisingly short. Look at Article 9. Then look at current news regarding Japan’s "Self-Defense Forces." You’ll see the friction between 1947 law and 2026 reality.

- Watch Post-War Cinema: Films by Akira Kurosawa or Yasujiro Ozu from the late 40s and early 50s aren't just art; they are primary sources. They capture the vibe of a country trying to find its soul in the shadow of American tanks.

- Acknowledge the Nuance: Don't fall for the "Great Liberator" narrative or the "Evil Imperialist" one. The truth is somewhere in the middle—a mix of genuine idealism, Cold War pragmatism, and raw survival.

The US occupation of Japan ended officially in 1952, but in many ways, it’s still happening. Every time a Japanese Prime Minister visits Washington, or a new base dispute breaks out in Okinawa, we’re seeing the ripples of MacArthur’s corncob pipe hitting the tarmac. It was a period of radical change that proved you can't just kill an enemy—you have to build something better to replace them. What was built wasn't American, and it wasn't the old Japan. It was something entirely new.