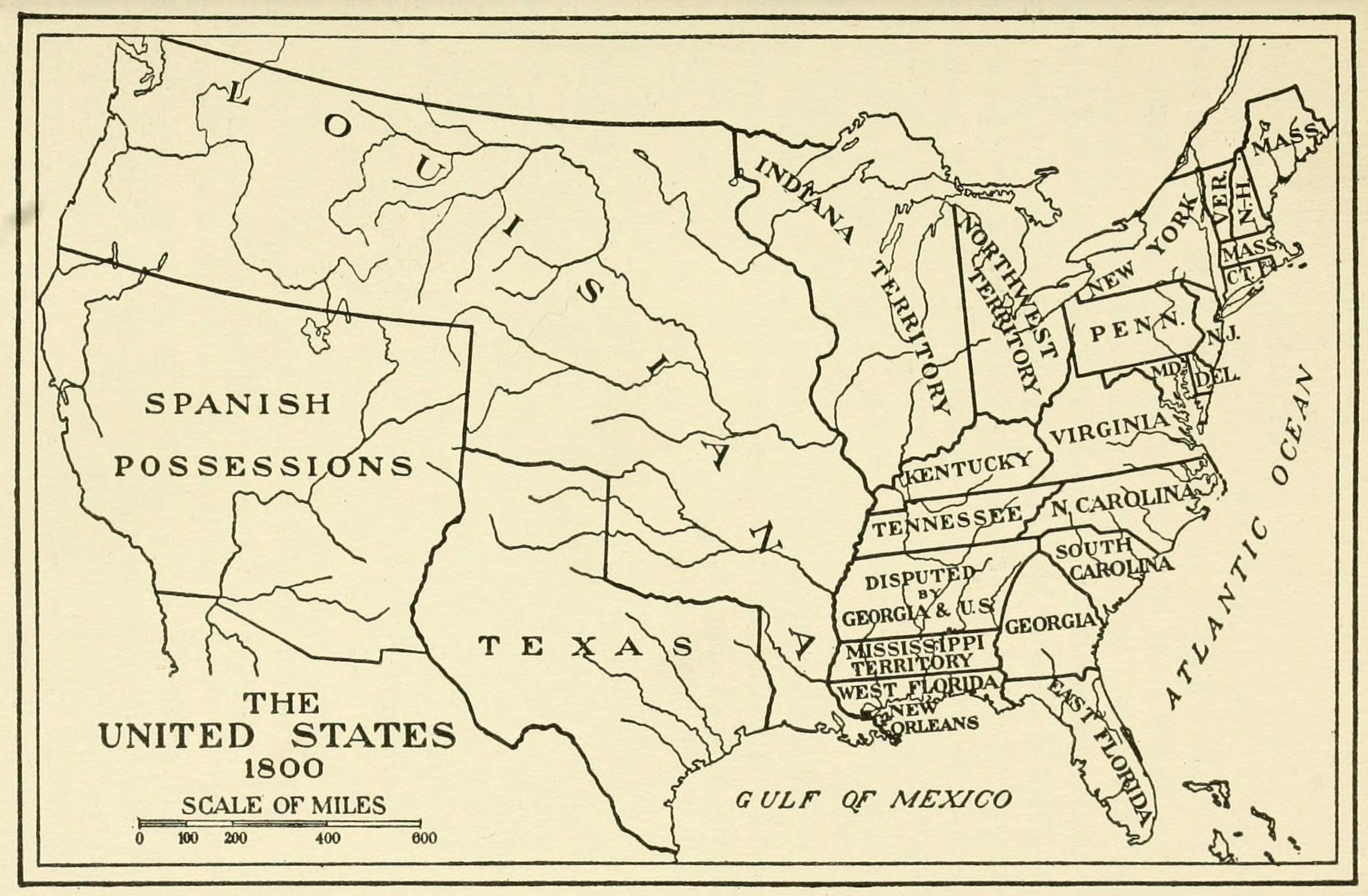

If you look at a US map in 1800s, it feels like looking at a rough draft of a painting where the artist kept changing their mind every ten minutes. It’s messy. It’s chaotic. Honestly, it’s a bit of a disaster compared to the clean, rectangular shapes we’re used to seeing on the back of a quarter or a modern atlas.

Back then, "The United States" wasn't a finished product. It was a shifting, breathing project. In 1800, the country basically stopped at the Mississippi River. Everything else? That was a massive "maybe."

You had European powers—Spain, France, Britain—clutching onto pieces of the continent like they were playing a high-stakes game of poker. Meanwhile, the actual people living there, the Indigenous nations, weren't exactly being consulted about these colorful lines being drawn on paper in Washington D.C. or Paris. By 1899, that map had transformed into something we recognize, but the journey from A to B was anything but a straight line.

The Great 1803 Reset: The Louisiana Purchase

Early on, the US map in 1800s changed overnight because of a guy in France who needed cash for his wars. Napoleon Bonaparte. He sold the Louisiana Territory to Thomas Jefferson for about $15 million. It sounds like a lot, but it was roughly three cents an acre. Total steal.

This single deal doubled the size of the country.

But here’s the thing: nobody actually knew where the borders were. It wasn't like they had GPS or satellite imagery. The negotiators in Paris were basically working off old, vague descriptions. This led to decades of arguments. Was the border at the Sabine River? The Red River? The Rocky Mountains?

Cartographers like Aaron Arrowsmith and later John Melish had to essentially guess where the rivers went once they got past a certain point. When you look at these old maps, you’ll see "unexplored" or "mountainous region" written across huge swaths of what is now Kansas or Nebraska. It’s wild to think that a map from 1810 was more of a "suggestion" than a legal document.

📖 Related: Food in Kerala India: What Most People Get Wrong About God's Own Kitchen

Texas, Mexico, and the messy southwest

By the 1840s, the US map in 1800s hit a fever pitch of expansion. This is the era of Manifest Destiny. It's a fancy term for the belief that the U.S. was destined to stretch from "sea to shining sea." But that land wasn't empty.

Texas is the biggest headache on the map during this period. For a while, it was its own country. The Republic of Texas. If you find a map from 1836 to 1845, Texas looks like a giant chimney reaching all the way up into modern-day Wyoming. It didn't have the "panhandle" shape we know today.

Then came the Mexican-American War.

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the U.S. suddenly swallowed California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Arizona and New Mexico. It was a massive land grab. If you’re a map collector, this is the most interesting decade. The boundaries were shifting so fast that printers couldn't keep up. You might buy a map in January that was factually incorrect by July.

The Gadsden Purchase in 1853 finally "finished" the southern border. The U.S. paid Mexico $10 million for a relatively small strip of land in southern Arizona and New Mexico. Why? For a railroad. They needed a flat route to get to California. History is often just a series of people trying to find the easiest way to move stuff from one place to another.

Why the lines are so straight (mostly)

Have you ever wondered why western states look like boxes while eastern states look like spilled ink?

👉 See also: Taking the Ferry to Williamsburg Brooklyn: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s because of the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance. This system really took hold as the US map in 1800s pushed west. Thomas Jefferson wanted a scientific way to divide land. He loved grids.

Surveyors would go out with chains and compasses. They ignored the hills. They ignored the valleys. They just drew straight lines based on latitude and longitude. This created the "Public Land Survey System." It’s why when you fly over the Midwest today, everything looks like a giant checkerboard.

But sometimes nature didn't cooperate.

Take the Missouri Compromise of 1820. It drew a line at $36°30'$ north latitude. This was a political line, not a geographic one. It was meant to decide where slavery could exist and where it couldn't. It's a dark part of the map's history. These lines weren't just about geography; they were about power, labor, and the deep-seated tensions that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

The Oregon Country and the 49th Parallel

Up north, things were just as weird.

For decades, the U.S. and Great Britain "shared" the Pacific Northwest. It was called the Oregon Country. It wasn't until 1846 that they finally settled on the 49th parallel.

✨ Don't miss: Lava Beds National Monument: What Most People Get Wrong About California's Volcanic Underworld

There was actually a slogan: "Fifty-four Forty or Fight!" People were ready to go to war over the border. Eventually, cooler heads prevailed, and the boundary was settled peacefully. This gave us the familiar top edge of Washington, Idaho, and Montana.

Without this treaty, the US map in 1800s would have ended much further south, or perhaps much further north into what is now British Columbia. Mapping was diplomacy by other means.

The "Great American Desert" Myth

One of the funniest—or most tragic, depending on how you look at it—parts of 19th-century mapping was the labeling of the Great Plains.

Major Stephen H. Long explored the region in the 1820s and called it the "Great American Desert." For decades, maps literally printed those words across the middle of the country. People thought nothing could grow there. They thought it was a wasteland.

This mistake kept people from settling in the middle of the country for a long time. It wasn't until later in the century, with the help of better irrigation and a few unusually wet years, that the "desert" label was scrubbed from the maps. It just goes to show that a map is only as good as the person who explored the dirt.

How to use this knowledge today

If you’re interested in history, or just want to understand why your state is shaped like a boot or a rectangle, looking at a US map in 1800s is the best place to start.

Here is how you can actually dive into this without getting bored:

- Check out the David Rumsey Map Collection. It’s a massive, free online database. You can overlay 1850s maps on top of Google Maps. Seeing a 150-year-old map of your hometown is a trip.

- Look for "Territory" maps. Before a state was a state, it was a territory. Often, these territories were massive. "Indiana Territory" used to include Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

- Find the "ghost" towns. Old maps often show towns that were bypassed by the railroad. Once the tracks went ten miles south, the town died. These are the forgotten spots on the US map in 1800s.

- Trace the river changes. Rivers like the Mississippi shift over time. Sometimes, a piece of land that was in Mississippi in 1820 is now on the "wrong" side of the river and technically in Louisiana. The map doesn't always match the water.

The 19th century was the era when the United States defined its physical identity. It was a century of land grabs, bad surveys, political compromises, and thousands of miles of walking through the woods with a compass. Every weird zig-zag in a state border has a story behind it—usually involving a surveyor who was tired, a politician who was greedy, or a river that refused to stay in its bed.