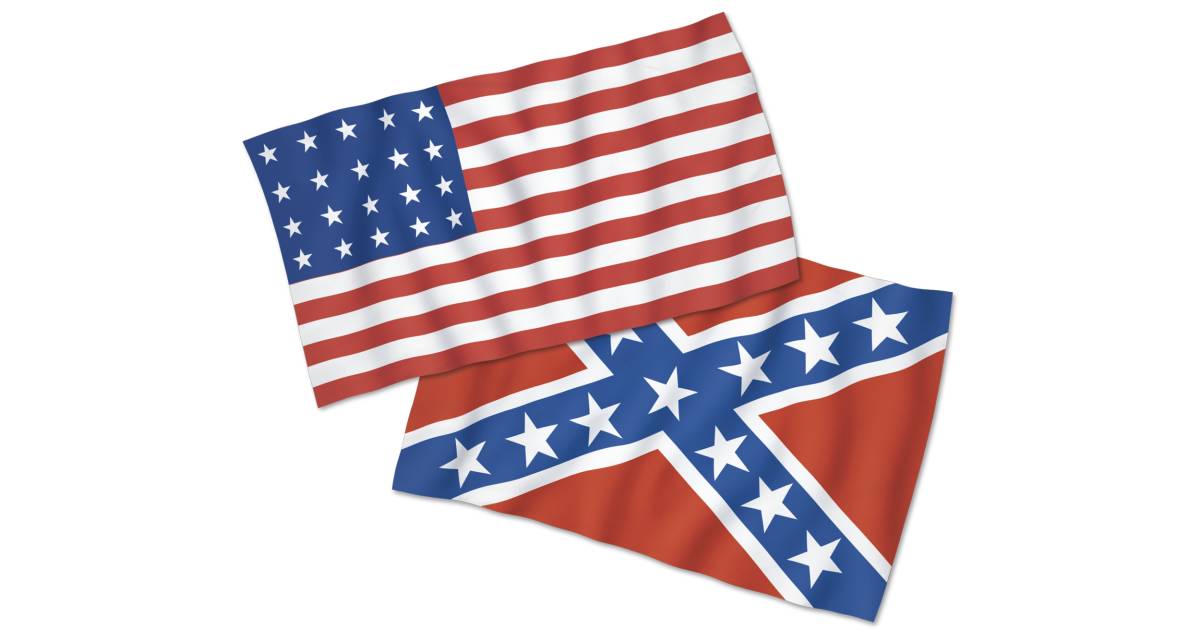

You’ve seen it in every grainy, sepia-toned photograph from the 1860s. It’s draped over the coffins of boys who never made it back to Ohio or Maine. It’s clutched by a color bearer charging into the "Bloody Lane" at Antietam. But honestly, the union flag during civil war wasn’t just one thing. It wasn't some static, unchanging icon that looked exactly like the one sitting in your garage right now. It was messy. It was evolving. It was a political statement in 13 stripes and a growing cluster of stars.

Most people assume the flag was a finished product. It wasn't.

When the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, the American flag was a work in progress. It’s kind of wild to think about, but there was no federal law back then dictating exactly how the stars had to be arranged. You had circular patterns, "great star" patterns where the small stars formed one giant star, and rows that looked like they were falling off the edge of the blue canton. It was a beautiful, chaotic mess of needlework and patriotism.

The 33, 34, and 35-Star Reality

Here is the thing that really trips people up: the Union never actually removed stars for the seceded states. Not one. Abraham Lincoln was adamant about this. In his mind, the Confederacy wasn't a separate country; it was a group of states in rebellion. To remove a star would be to admit that the South was actually gone.

So, when the war kicked off in April 1861, the official union flag during civil war had 33 stars. But that didn't last long. Kansas joined the party as the 34th state just as the country was tearing itself apart. Then, in the middle of the carnage in 1863, West Virginia split off from Virginia and stayed loyal to the North. Boom—35 stars.

👉 See also: White Nails with Gems: Why This Wedding Classic is Taking Over Streetwear

If you’re looking at a "Civil War flag" and it has 50 stars, it’s a cheap replica. If it has 13 stars, it’s a Revolutionary War throwback. To be authentic to the actual conflict, you’re looking for that 34 or 35-star count.

Why the Design Kept Changing

Every time a new state was added, the flag changed on the following July 4th. It’s a bit weird to imagine a country redesigning its primary symbol in the heat of a total war, but that’s exactly what happened. The 34-star flag flew over the darkest days of 1861 and 1862. It saw the horror of Shiloh and the drowning mud of the Peninsula Campaign.

By the time the 35-star flag became official in 1863, the war had shifted. This was the flag of Gettysburg. This was the flag that flew when the Emancipation Proclamation started to truly change the "why" of the war.

Regimental Colors vs. The National Flag

We need to talk about what soldiers actually carried. If you were a private in the 20th Maine, you weren't just looking for "The Stars and Stripes." You were looking for your Regimental Color.

In the 19th century, smoke from black powder was so thick you couldn't see your hand in front of your face after a few volleys. Communication was basically impossible. The union flag during civil war served as a literal GPS. If you could see the flag, you knew where your friends were. If the flag moved forward, you moved forward. If it fell, you were probably about to be overrun.

Standard Union infantry regiments usually carried two flags:

- The National Color (The Stars and Stripes).

- The Regimental Color (usually a blue field with an eagle and the regiment's name).

These flags were huge. They were roughly 6 feet by 6 feet. Imagine trying to run through a forest or across a plowed field while holding a massive silk banner on a heavy wooden pole while people are actively trying to kill you. Because that’s exactly what the color guard did. Being a color bearer was basically a death sentence, yet men fought for the "honor" of doing it.

The Blood and the Silk

At the Battle of Gettysburg, the 24th Michigan (part of the famous Iron Brigade) lost nine color bearers in a single day. Nine. As soon as one man was shot, another would drop his rifle and pick up the flag. It wasn't about the fabric. It was about what the flag represented—the survival of the Union itself.

There's a famous story from the Battle of the Crater where a Union soldier wrapped the flag around his body to keep it from being captured. These weren't just decorations; they were the soul of the unit. Many of these flags, now housed in state capitals and museums like the Smithsonian, are riddled with "battle honors." If a regiment fought well, they were allowed to paint the names of their battles—Antietam, Fredericksburg, Vicksburg—directly onto the stripes.

The Logistics of 19th Century Flag Making

Where did all these flags come from? It's not like they were being mass-produced in a factory in China.

Most of the official government-issue flags were made at the Schuylkill Arsenal in Philadelphia. They used high-quality silk or wool bunting. The stars were often hand-sewn or appliquéd. But here is a detail most movies miss: many flags were "presentation colors."

Basically, a town would raise a company of volunteers, and the local ladies' sewing circle would spend weeks hand-stitching a flag for "their" boys. These flags were often incredibly ornate, featuring gold fringe, hand-painted slogans, and unique star patterns. Some even had "The Union Forever" embroidered across the middle. When these units got to the front, their flags looked nothing like the standard-issue ones.

Over time, the weather and the war destroyed these beautiful handmade gifts. By 1864, many veteran units were carrying tattered rags that were barely recognizable as a union flag during civil war. They refused to replace them because the rags had "seen the elephant"—they had been through the fire.

Gold Fringe and Weird Star Patterns

You’ll sometimes see modern "sovereign citizen" types arguing that gold fringe on a flag means it’s a military flag or that the law is different. During the Civil War, gold fringe was just... fancy. It didn't have a secret legal meaning. It was an embellishment used on parade flags and regimental colors to make them look more impressive.

As for the stars, the "Medallion" pattern was quite popular. This featured a large central star surrounded by two circles of smaller stars. It looks stunning, but it was a nightmare to sew. As the war dragged on, the military pushed for simpler "linear" rows because they were faster to produce.

💡 You might also like: States with Social Security No Tax: The Real Way to Keep Your Benefit Check Whole

The Flag as a Weapon of Peace

By 1865, the flag had become a symbol of a hard-won victory. When Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, there wasn't a massive flag-raising ceremony like you see in the movies. It was a quiet affair. But when the news hit the North, the union flag during civil war suddenly appeared everywhere.

It was on storefronts. It was on lapels. It was draped over the balconies of theaters—including Ford's Theater, where a specific flag became part of a national tragedy.

The Flag that "Caught" Booth

When John Wilkes Booth jumped from the state box after shooting Lincoln, he supposedly tripped on a flag draped over the railing. Specifically, it was the Treasury Guard's flag (a blue flag with an eagle) and potentially a 36-star flag (Nevada had just been added). His spur caught in the fabric, causing him to land awkwardly and break his leg. In a strange twist of fate, the symbol of the Union he tried to destroy ended up being his undoing.

How to Identify an Authentic Civil War Union Flag

If you’re a collector or a history buff, you have to be careful. There are a lot of fakes out there. Here’s what real experts look for:

- Star Count: As mentioned, 33 (very early), 34, or 35 are the big ones. A 36-star flag exists but only at the very tail end of the war.

- Material: It should be silk or wool bunting. Cotton was used, but it was much rarer for military-grade flags.

- Sewing: Look for hand-stitched zig-zag patterns on the stars. Machine stitching did exist (the sewing machine was invented in the 1840s), but many flags were still hand-finished.

- Dimensions: Regimental flags were almost always square-ish (6x6 or 5x5 feet), while navy flags and garrison flags were much longer rectangles.

Why This Still Matters

The flag we have today—the 50-star version—is the direct descendant of the one that survived 1861-1865. The Civil War was the moment the United States shifted from being a plural noun ("the United States are") to a singular noun ("the United States is"). The flag reflects that. It stopped being a collection of state interests and started being a single, national identity.

When you look at a union flag during civil war, you aren't just looking at a piece of fabric. You're looking at a survival story. It's a reminder that the country almost didn't make it.

✨ Don't miss: Wait, What is That Cut Actually Called? Names of Short Haircuts Explained

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the history of the Union flag, don't just look at Wikipedia. Do these three things:

- Visit State Archives: Most Union states (like Pennsylvania, New York, and Ohio) have massive collections of their original "battle flags." These are often kept in climate-controlled rooms and aren't always on display, but many have digital archives where you can see the specific damage and "battle honors" of each flag.

- Study the "Great Star" Pattern: Search for the "Great Star" or "Medallion" star arrangements. It shows the incredible artistic variety that existed before the government standardized everything in the early 20th century.

- Check the 1861-1865 Statehood Dates: If you find a flag with 37 stars, you know it’s post-war (Nebraska, 1867). Matching the star count to the specific year of the war is the fastest way to date a historical site or photograph.

The flag was the only thing that stayed constant while everything else fell apart. Seeing it in person, tattered and blood-stained, makes the history feel a lot less like a textbook and a lot more like a reality.