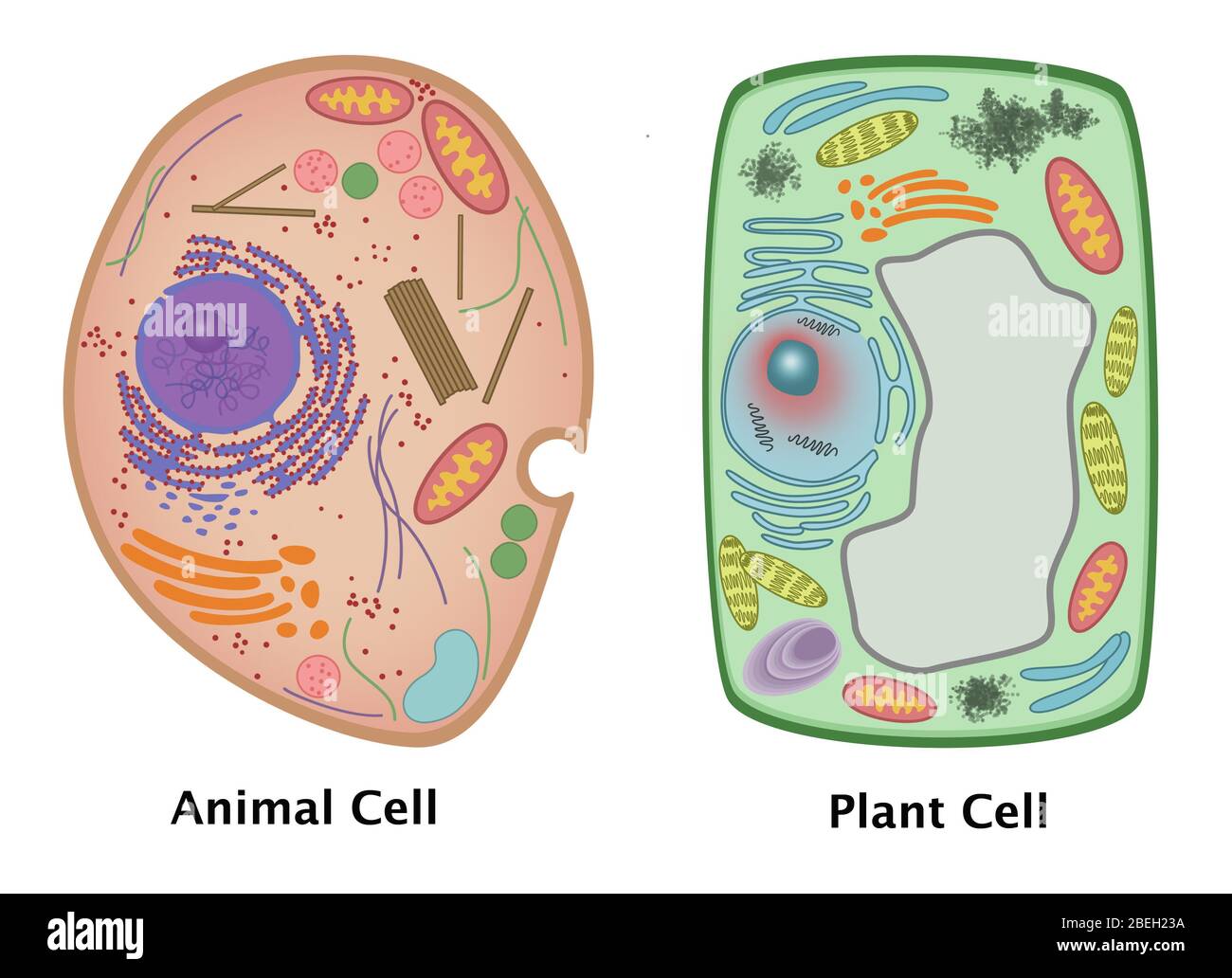

You’ve seen them in every middle school textbook since the 1990s. The picture of an animal cell and plant cell usually looks like a fried egg sitting next to a green brick. It’s a classic visual shorthand. But honestly, those diagrams are kinda lying to you. They represent a "typical" cell that doesn't actually exist in nature in that exact, perfect form. Real life is messier.

Cells are the building blocks of everything. Your skin, the oak tree outside, the mold on that bread you forgot to toss—all of it comes down to these tiny, microscopic factories. When we look at a picture of an animal cell and plant cell, we’re seeing a map of biological machinery. One is built for movement and flexibility. The other is a fortified fortress designed to stand tall against gravity without a skeleton.

Why the Shapes Look So Different

Go ahead and pull up a standard picture of an animal cell and plant cell. You’ll notice the animal cell is usually drawn as a blobby circle. This isn't just an artistic choice. Animal cells lack a rigid outer wall because animals need to move. If your muscle cells were encased in hard boxes, you’d be as stiff as a board. Instead, they have a flexible plasma membrane. This phospholipid bilayer is basically a fluid mosaic—a gatekeeper that lets things in and out while remaining squishy enough to change shape.

Plant cells are the opposite. They’re usually depicted as rectangular or hexagonal. This is because of the cell wall, made of cellulose. Think of it like the wooden frame of a house. Because plants don't have bones, they rely on the collective strength of these rigid walls and something called turgor pressure to stay upright. If you’ve ever seen a wilted plant, you’re seeing what happens when those cells lose water and the pressure drops.

The Organelles They Share

Despite the shape differences, these two have a lot in common. Both are eukaryotic, meaning they keep their DNA tucked away in a nucleus. In any decent picture of an animal cell and plant cell, you’ll see that purple or blue orb right in the middle (or pushed to the side in plants). That’s the brain. It holds the blueprints.

Then you have the mitochondria. The "powerhouse" meme is tired, but it’s accurate. These are the engines. They take glucose and turn it into ATP through cellular respiration. Interestingly, mitochondria have their own DNA, which has led scientists like Lynn Margulis to propose the endosymbiotic theory—the idea that mitochondria were once independent bacteria that got swallowed by a larger cell and just decided to stay. It’s a biological roommate situation that lasted billions of years.

👉 See also: How to Log Off Gmail: The Simple Fixes for Your Privacy Panic

You’ve also got the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) and the Golgi apparatus. The ER is the factory floor where proteins and lipids are made. The Golgi is the shipping center. It packages things into vesicles and sends them where they need to go. If you’re looking at a picture of an animal cell and plant cell, the Golgi usually looks like a stack of flattened pancakes.

The Green Stuff: Plant Exclusives

If you’re looking at a picture of an animal cell and plant cell and trying to tell them apart quickly, look for the green bits. Those are chloroplasts. Animals don't have them because we eat our energy. Plants make theirs from scratch.

Chloroplasts contain chlorophyll, which captures sunlight to drive photosynthesis. This is essentially the most important chemical reaction on Earth. Without it, there’s no oxygen for us to breathe and no base for the food chain.

Another huge difference is the vacuole. In an animal cell, vacuoles are small and temporary. In a plant cell, there’s usually one massive Central Vacuole that takes up like 90% of the space. It’s basically a giant water balloon. It stores nutrients, waste, and, most importantly, provides that turgor pressure I mentioned earlier. When the vacuole is full, the plant stands tall. When it’s empty, the plant flops.

The Animal Edge: Centrioles and Lysosomes

While plants have their walls and green energy pods, animal cells have their own specialized gear. Look closely at a picture of an animal cell and plant cell and you might see tiny, pasta-shaped structures in the animal side called centrioles. These are crucial for cell division. They help pull chromosomes apart when the cell is ready to split in two. While some "lower" plants have them, most complex land plants get along fine without them.

✨ Don't miss: Calculating Age From DOB: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

Then there are lysosomes. These are the "suicide bags" or "stomach" of the cell. They contain digestive enzymes that break down waste. While plant cells have vacuole-like structures that do some of this, lysosomes are much more prominent in animal cells because animals take in complex organic matter that needs to be dismantled.

Don't Let the Diagrams Fool You

Here’s the thing: most pictures are 2D. In reality, a cell is a 3D crowded room. It’s packed. There isn't just empty "cytoplasm" space where things float around like islands in an ocean. The cytoplasm is actually reinforced by a cytoskeleton—a network of protein fibers that act like scaffolding.

Furthermore, the "typical" cell in a picture of an animal cell and plant cell doesn't account for specialization.

- Neurons: These animal cells have long tails (axons) that can be three feet long.

- Red Blood Cells: They don’t even have a nucleus! They spit it out to make more room for oxygen.

- Xylem Cells: In plants, these cells actually die to become hollow tubes that transport water.

When you look at these diagrams, you're looking at a map, not the territory. It’s a simplified version to help our brains categorize the chaos of life.

How to Memorize the Differences Fast

If you’re studying for a bio exam or just curious, keep it simple. Focus on the "Three Cs" for plants: Cell Wall, Chloroplasts, and Central Vacuole. If a cell has those, it's a plant. If it's squishy, irregular, and has centrioles, it’s an animal.

🔗 Read more: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

It’s also worth noting the size. Generally, plant cells are larger than animal cells. You can actually see some plant cells with a very basic microscope, whereas animal cells often require a bit more magnification and staining to see the details clearly.

Why This Matters for Technology and Medicine

Understanding the picture of an animal cell and plant cell isn't just for passing a test. It’s how we develop medicine. For example, many antibiotics work by attacking the cell wall. Since human (animal) cells don't have cell walls, the medicine kills the bacteria without hurting you.

In the world of biotech, we use these differences to create things like biofuels from plant cellulose or to grow "lab-grown meat" by culturing animal muscle cells in a petri dish. We are literally hacking the structures seen in these diagrams to solve global problems.

Your Next Steps for Mastering Cell Biology

To truly understand how these systems work beyond a static image, you should move from 2D diagrams to 3D models or real-world observation.

- Get a cheap compound microscope: You can see the rectangular cell walls of an onion skin or the chloroplasts in Elodea leaves right in your kitchen. It’s way cooler than a drawing.

- Use interactive 3D cell explorers: Sites like "Cells Alive!" or BioDigital allow you to rotate the cell and see how the organelles overlap and interact in a three-dimensional space.

- Study the Cytoskeleton: Most basic pictures leave this out. Research "microtubules" and "actin filaments" to see how cells actually maintain their shape and move things around internally.

- Look at Electron Micrographs: Search for "TEM" (Transmission Electron Microscope) images of cells. They won't be pretty and colorful like a textbook, but they show the gritty, complex reality of what's actually happening inside you right now.

The journey from a simple picture of an animal cell and plant cell to understanding the molecular machinery of life is a big leap, but it starts with recognizing those basic shapes and knowing exactly what they’re hiding.