It starts small. Maybe it was a simple ear piercing, a rogue pimple on your chest, or that time you fell off your bike and scraped your shoulder. Most people heal and move on. Their skin knits itself back together, leaves a faint white line, and that’s the end of the story. But for some of us, the body doesn't know when to quit. The repair crew stays on the clock long after the job is finished. The result is a thick, rubbery, often itchy mound of tissue that spills over the borders of the original wound. It’s a keloid. Honestly, it can be frustrating as hell.

Understanding the causes of keloid scarring isn't just about knowing you have "bad genes." It’s a complex biological glitch. While most scars fade, keloids are technically benign tumors made of collagen. They don't turn into cancer, thank goodness, but they can be painful, tender, and—let's be real—a massive blow to your self-esteem.

The Biological Glitch: What’s Actually Happening Under Your Skin?

Why does this happen? Basically, your skin is a master of wound healing, a process involving inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. In a "normal" person, fibroblasts (the cells that make collagen) produce just enough material to bridge a gap. Once the gap is closed, the body sends a "stop" signal.

In people prone to keloids, that signal is never received. The fibroblasts go into overdrive. They keep pumping out Type I and Type III collagen like a factory with a broken off-switch. According to researchers like Dr. Rei Ogawa, a world-renowned expert in keloid research at Nippon Medical School, mechanobiology plays a huge role here. This means that physical tension on the skin—the literal pulling and stretching of your hide—tells those cells to keep building. This is why you rarely see keloids on your eyelids or genitals (where skin is loose) but see them constantly on the chest, shoulders, and earlobes.

It’s Not Just One Thing

It’s usually a "perfect storm" of factors. You need the genetic predisposition, a trigger (the injury), and often, a specific location on the body that is under tension.

Genetics: The Card You Were Dealt

We have to talk about the elephant in the room. If your parents have keloids, you’re much more likely to get them. It sucks, but it’s the reality. Studies have shown a strong familial link, and certain ethnicities are hit much harder than others.

✨ Don't miss: The Back Support Seat Cushion for Office Chair: Why Your Spine Still Aches

People of African, Asian, and Hispanic descent have a significantly higher risk—some estimates suggest up to 15 times higher than those with lighter skin tones. Why? We don't fully know yet. Some scientists point to the NEDD4 gene or variations in the FOXL2 gene as potential culprits. It’s not a single "keloid gene," but rather a cluster of genetic markers that make your inflammatory response more aggressive than average.

The Triggers: It Doesn't Take Much

You might think you need a major surgery to trigger a keloid. Nope. While surgical incisions are a common cause of keloid scarring, the trigger can be surprisingly minor.

- Acne and Folliculitis: This is a big one. Deep cystic acne on the back or chest creates localized inflammation. When that inflammation lingers, it can transition directly into a keloid.

- Body Piercings: The earlobe is the classic spot. Because a piercing is a "permanent" wound that the body tries to heal around a foreign object, it's a prime target for overgrowth.

- Vaccinations: That little "BCG" scar many people have? In keloid-prone individuals, that tiny needle prick can turn into a grape-sized growth.

- Tattoos: The repeated trauma of the needle into the dermis is sometimes enough to kickstart the collagen factory.

Interestingly, there are cases of "spontaneous keloids" where the person doesn't remember an injury at all. Usually, these are actually reactions to microscopic trauma or internal tension that we just didn't notice.

Hormones and the Age Factor

Have you noticed that kids rarely get keloids? And elderly people don't see them pop up as often either? Most keloids develop between the ages of 10 and 30.

Puberty is a massive risk window. Hormones, specifically growth hormones and potentially estrogen, seem to fuel the fire. Pregnant women often report that their existing keloids grow larger or become more symptomatic during gestation. There’s a clear link between systemic growth signals in the body and the localized growth of these scars. If your body is in "grow mode," your scars might take that instruction a bit too literally.

🔗 Read more: Supplements Bad for Liver: Why Your Health Kick Might Be Backfiring

Why Is Location Everything?

You’ll almost never find a keloid on the palm of your hand or the sole of your foot. Why? These areas don't have the same type of "skin tension" as your mid-chest or your deltoids.

Think about your chest. Every time you breathe, your skin stretches. Every time you move your arms, that skin is pulled. This constant mechanical stress irritates the fibroblasts. It’s like trying to heal a crack in a wall while someone is constantly shaking the house. The body gets "frustrated" and just keeps throwing cement (collagen) at the problem.

Misconceptions: What It Isn't

Let's clear some things up. Keloids are not contagious. You can't "catch" them from someone else. They also aren't "dirty" scars. Having them doesn't mean you didn't clean your wound properly. In fact, sometimes over-cleaning a wound with harsh chemicals like hydrogen peroxide can increase inflammation and actually increase the risk.

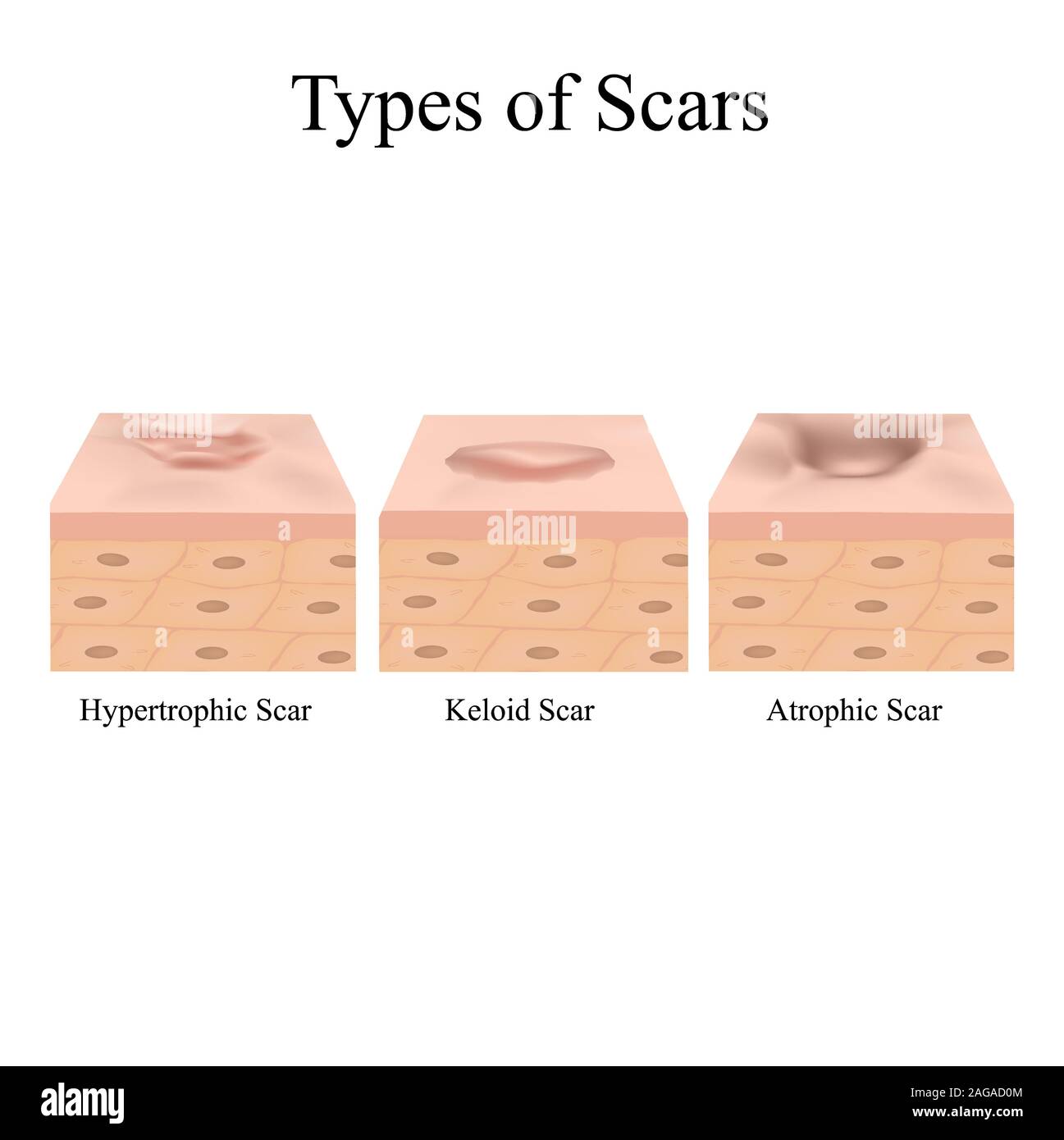

Also, a keloid is NOT the same as a hypertrophic scar. People mix these up all the time.

- Hypertrophic Scars: Stay within the boundaries of the original wound. They often get better on their own after a year or two.

- Keloids: Spread like a wildfire beyond the original cut. They rarely, if ever, go away without medical intervention.

Can You Actually Prevent Them?

If you know you're prone to them, prevention is your only real defense. Once a keloid is there, it's notoriously hard to kill. Surgery alone has a failure rate of nearly 100%—the act of cutting out a keloid just creates a new, bigger wound, which then turns into an even bigger keloid.

💡 You might also like: Sudafed PE and the Brand Name for Phenylephrine: Why the Name Matters More Than Ever

If you are prone to these growths, you need to be cautious.

- Avoid unnecessary piercings or tattoos.

- Treat acne aggressively and early to prevent deep inflammation.

- If you have to have surgery, tell your surgeon beforehand. They can use special suturing techniques to reduce tension, or even plan for "prophylactic" treatments like steroid injections or superficial radiation right after the procedure.

Real Treatment Realities

Treatment is a marathon, not a sprint. Most dermatologists start with intralesional corticosteroid injections. These help flatten the scar and stop the itching by suppressing the inflammatory response. But it takes multiple sessions. It hurts. And it doesn't always work.

Cryotherapy (freezing the scar from the inside out) is becoming more popular. There’s also silicone gel sheeting, which works by hydrating the area and slightly reducing the "tension" signals sent to the cells. It sounds too simple to work, but if worn 12–24 hours a day for months, it can make a massive difference.

For the most stubborn cases, doctors use a combination of surgery followed immediately by SRT (Superficial Radiation Therapy). By lightly radiating the area, they "kill" the overactive fibroblasts so they can't regrow. It’s effective, but it’s a big commitment.

Actionable Next Steps for Managing the Risk

If you're dealing with a new injury and you're worried about the causes of keloid scarring, here is what you should actually do:

- Pressure Therapy: If you get an ear piercing and notice a small bump, use a pressure earring immediately. Constant pressure can starve the excess collagen of blood flow and stop its growth.

- Silicone Sheets: Don't wait for a keloid to form. If you have a surgical scar, apply silicone sheets as soon as the wound is closed. This is the gold standard for at-home prevention.

- Sun Protection: New scars are incredibly sensitive to UV light. Sun exposure can darken a keloid (hyperpigmentation), making it much more noticeable and permanent. Use SPF 50 or keep it covered.

- Don't "Wait and See": If a scar starts to feel itchy, painful, or looks like it's growing beyond the original cut, see a dermatologist immediately. Early-stage keloids respond way better to steroids than old, "woody" ones.

- Consult a Specialist: If you have a family history, talk to a derm before any elective surgery. They might suggest a different approach to your recovery that could save you years of discomfort.

The reality is that we can't change our DNA. We can't change the way our fibroblasts are wired. But by understanding the mechanical and hormonal triggers that cause these scars, we can at least stop the "factory" before it gets out of hand. Your skin is just trying to protect you; sometimes it just needs a little help knowing when the war is over.