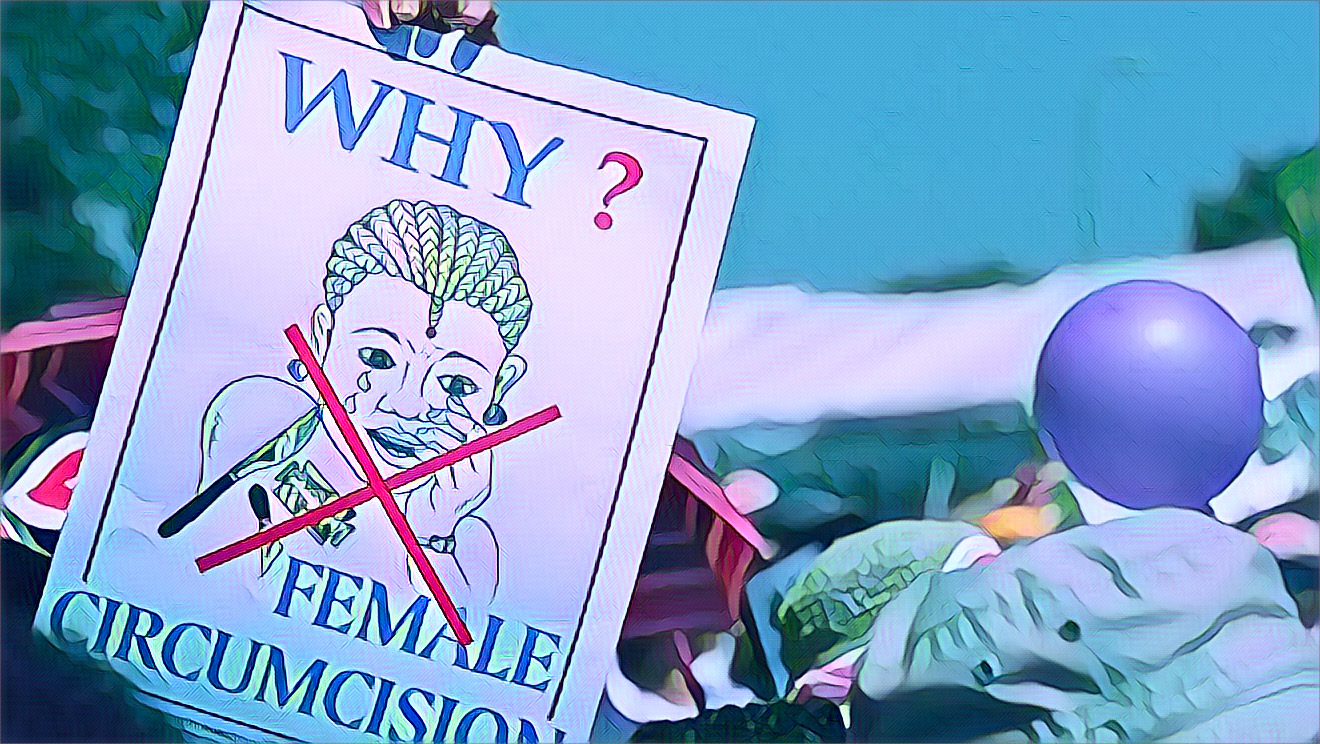

It is a Tuesday in a rural village in the Tana River County of Kenya. For most, it's just another hot afternoon. But for a group of young girls, the air is thick with a specific kind of dread. They aren't going to school today. Instead, they are being led to a secluded hut. This isn't ancient history. It is happening right now, in 2026, even as global health organizations scream for it to stop. Africa female genital cutting (FGC)—often referred to as female genital mutilation (FGM)—remains one of the most complex, deeply entrenched health and human rights issues on the continent.

We need to be real for a second.

When Westerners talk about this, they usually dive straight into "barbarism" or "savagery." That doesn't help anyone. If we want to understand why a mother would allow her daughter to be cut, we have to look at the social glue that holds these communities together. It's about marriageability. It's about belonging. It's about a misguided sense of purity that has been passed down through so many generations that the original "why" has been lost to time.

What are we actually talking about?

Let's get the clinical stuff out of the way because terms matter. The World Health Organization (WHO) breaks this down into four types. It ranges from Type I, which is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans, to Type III, known as infibulation. This involves narrowing the vaginal opening by creating a seal. Type IV is basically a catch-all for any other harmful procedures like piercing or scraping.

It's painful. It’s dangerous. And honestly, it has zero medical benefits.

According to UNICEF data, over 200 million women and girls alive today have undergone the procedure. While it happens in parts of Asia and the Middle East, the highest concentration of cases remains in Africa. We are talking about 28 countries across the continent where this is a recognized practice. In places like Somalia, Guinea, and Djibouti, the prevalence rates hover near 90%. That is a staggering number of women living with the long-term physical and psychological fallout of a few minutes of trauma.

Why Africa female genital cutting is so hard to stop

You'd think passing a law would fix it. Most African nations have actually banned the practice. In Egypt, the laws are strict. In Ethiopia, there are heavy penalties. Yet, the cutting continues. Why? Because in many rural pockets, the local law—the "traditional" law—carries more weight than the constitution written in a faraway capital city.

👉 See also: Does Birth Control Pill Expire? What You Need to Know Before Taking an Old Pack

Take the "cutter" for example.

In many villages, the woman who performs the procedure is a respected elder. She is often the midwife. She’s the person people turn to when they are sick. This is her livelihood. When an NGO tells her to stop, they are essentially asking her to give up her social status and her paycheck. It's a tough sell. Plus, there is the intense social pressure on the girls themselves. If you aren't cut, you might be labeled "unclean." You might be told no man will ever marry you. In a society where marriage is the only path to economic security, that's a death sentence.

The Rise of "Medicalization"

Here is a weird and frustrating trend: medicalization.

In countries like Egypt and Sudan, a huge percentage of these procedures are now performed by doctors and nurses in clinics rather than by traditional practitioners with rusty blades. They use anesthesia. They use sterile tools. Some healthcare providers argue they are "reducing harm."

But the WHO and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) are very clear: medicalization does not make it okay. It still violates the girl's bodily integrity. It still reinforces the idea that female bodies need to be "corrected" or controlled. By bringing it into a hospital, you're just giving a human rights violation a clean coat of white paint. It makes the practice seem "safe" and "scientific," which actually makes it harder to eradicate.

The Health Consequences Nobody Likes to Discuss

The immediate risks are obvious. Hemorrhage. Sepsis. Shock. When you use a non-sterile instrument on a child, things go south fast. But the long-term stuff is what really grinds down a woman's quality of life.

✨ Don't miss: X Ray on Hand: What Your Doctor is Actually Looking For

- Chronic Pain: We're talking about nerve damage that lasts decades.

- Childbirth Complications: Women who have undergone Type III cutting are significantly more likely to experience obstructed labor. This leads to obstetric fistula—a condition where a hole develops between the birth canal and the bladder or rectum. It leads to constant leaking and social ostracization.

- Psychological Trauma: PTSD is common. Many women report feelings of betrayal by their parents.

- Recurrent Infections: Cysts and urinary tract infections become a way of life.

Dr. Nafissatou Diop, a long-time expert in this field, has frequently highlighted that the "silent" complications—like the loss of sexual pleasure or the pain during intercourse—are often ignored because they are taboo to talk about in conservative settings.

Real Progress: The Power of the "Public Declaration"

It isn't all gloom. Things are moving. Tostan, an NGO working in West Africa, pioneered a model that actually works. They don't just show up and lecture people. They engage in three-year-long community education programs. They talk about human rights, health, and democracy.

The turning point happens during a "Public Declaration." This is when an entire group of villages gets together and publicly vows to end the practice. Why is this important? Because it solves the "marriageability" problem. If every family in the neighboring ten villages agrees not to cut their daughters, then no girl is left behind. The social pressure flips. Suddenly, the "clean" thing to do is to keep your daughter intact.

In Senegal, thousands of communities have abandoned the practice using this method. It's a bottom-up approach rather than a top-down mandate.

The Role of Men and Religious Leaders

For a long time, FGC was treated as a "women's issue." Men weren't involved. They didn't know the details. Many men in these communities actually believed that women preferred to be cut or that it was a religious requirement.

Actually, it's not.

🔗 Read more: Does Ginger Ale Help With Upset Stomach? Why Your Soda Habit Might Be Making Things Worse

Leading Islamic scholars from Al-Azhar University in Cairo have stated clearly that female genital cutting has no basis in the Quran. It's a cultural practice, not a religious one. When male elders and imams start speaking out against it, the needle moves. In The Gambia, we’ve seen activists like Jaha Dukureh lead massive campaigns that force men to confront the reality of what their wives and daughters are going through.

Nuance is Everything

We have to acknowledge that "Africa" is not a monolith. The experience of a girl in urban Lagos is worlds away from a girl in the mountains of Ethiopia. In some places, the practice is disappearing rapidly. In others, it is actually increasing due to conflict and displacement. When societies break down, people often cling harder to traditional markers of identity, even the harmful ones.

COVID-19 was a massive setback. School closures meant girls were stuck at home, away from teachers who might have spotted the warning signs. In many regions, the "cutting season" was extended. We are still catching up to the damage done during those years.

How to Support the End of Africa Female Genital Cutting

If you actually want to see this end, you have to support the people on the ground. Western "savior" complexes usually backfire. When a foreign organization comes in and tells people their culture is "evil," the community tends to get defensive and double down.

Real change comes from:

- Supporting Local Grassroots Organizations: Groups like the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices (IAC) understand the cultural nuances. They know who to talk to.

- Focusing on Girl's Education: There is a direct statistical link between a girl’s education level and the likelihood she will have her daughter cut. Education provides the economic independence that makes the "marriageability" argument irrelevant.

- Legislative Advocacy: Keeping the pressure on governments to not just pass laws, but to fund the enforcement of those laws.

- Engaging the Diaspora: Many girls living in Europe or North America are taken back to their home countries during summer vacations for "the cut." Strengthening protections for these girls is vital.

The goal isn't just to stop a blade. The goal is to change the mindset that says a woman’s value is tied to her physical modification. It’s about bodily autonomy.

Practical Steps for Advocates and Professionals

If you are working in healthcare or international development, or even if you're just an informed citizen wanting to contribute, here are the most effective ways to engage with the issue of Africa female genital cutting today:

- Fund Community-Led Dialogues: Instead of one-off workshops, look for programs that facilitate long-term conversation within villages. This is the Tostan model mentioned earlier; it creates lasting change by altering the social norm collectively.

- Prioritize Maternal Health Integration: Support initiatives that integrate FGC education into prenatal and postnatal care. Midwives are often the most trusted voices in these communities; training them to be advocates against the practice is a high-leverage strategy.

- Advocate for Data Accuracy: Many countries under-report cases due to the stigma and illegality of the practice. Supporting independent research and data collection helps organizations allocate resources where they are most needed.

- Support Alternative Rites of Passage (ARP): In many cultures, the cutting is part of a "coming of age" ceremony. Some communities have successfully replaced the cutting with "circumcision by the words," where girls go through the same educational and celebratory rituals—without the physical harm. This honors the culture while protecting the child.

- Focus on the Legal System: Work with legal aid organizations that protect girls who run away from home to avoid being cut. Safe houses in Kenya and Tanzania provide refuge, but they are often underfunded and over-capacity.

Ending this practice isn't about erasing culture. It’s about evolving it. It's about ensuring that the next generation of girls in Africa can enter adulthood with their bodies, their health, and their futures fully intact. While the progress is slow, it is real. Every public declaration, every educated girl, and every doctor who refuses to perform the procedure brings us closer to a world where "the cut" is a memory rather than a reality.