Most people grew up with a spider named Charlotte or a mouse named Stuart. They’re the heavy hitters of children's literature. But then there’s Louis. He’s a Trumpeter Swan born without a voice. No "ko-hoh." Nothing. Just silence. Honestly, The Trumpet of the Swan is a weird book, even by E.B. White’s standards. It involves a bird playing a brass instrument, a heist at a music store, and a swan staying at the Ritz in Boston. It sounds ridiculous when you say it out loud. Yet, it works. It works because it’s a story about the lengths we go to for the people—or birds—we love.

White published this in 1970. He was older then. You can feel that in the prose. It’s got this ruminative, slightly stubborn quality to it. Unlike Charlotte’s Web, which feels like a perfect, enclosed ecosystem, The Trumpet of the Swan is sprawling. It travels from the wild marshes of Canada to the urban sprawl of Philadelphia. It’s a travelogue of the soul. Or at least, a travelogue of a very determined waterfowl.

The Problem With Being a Silent Swan

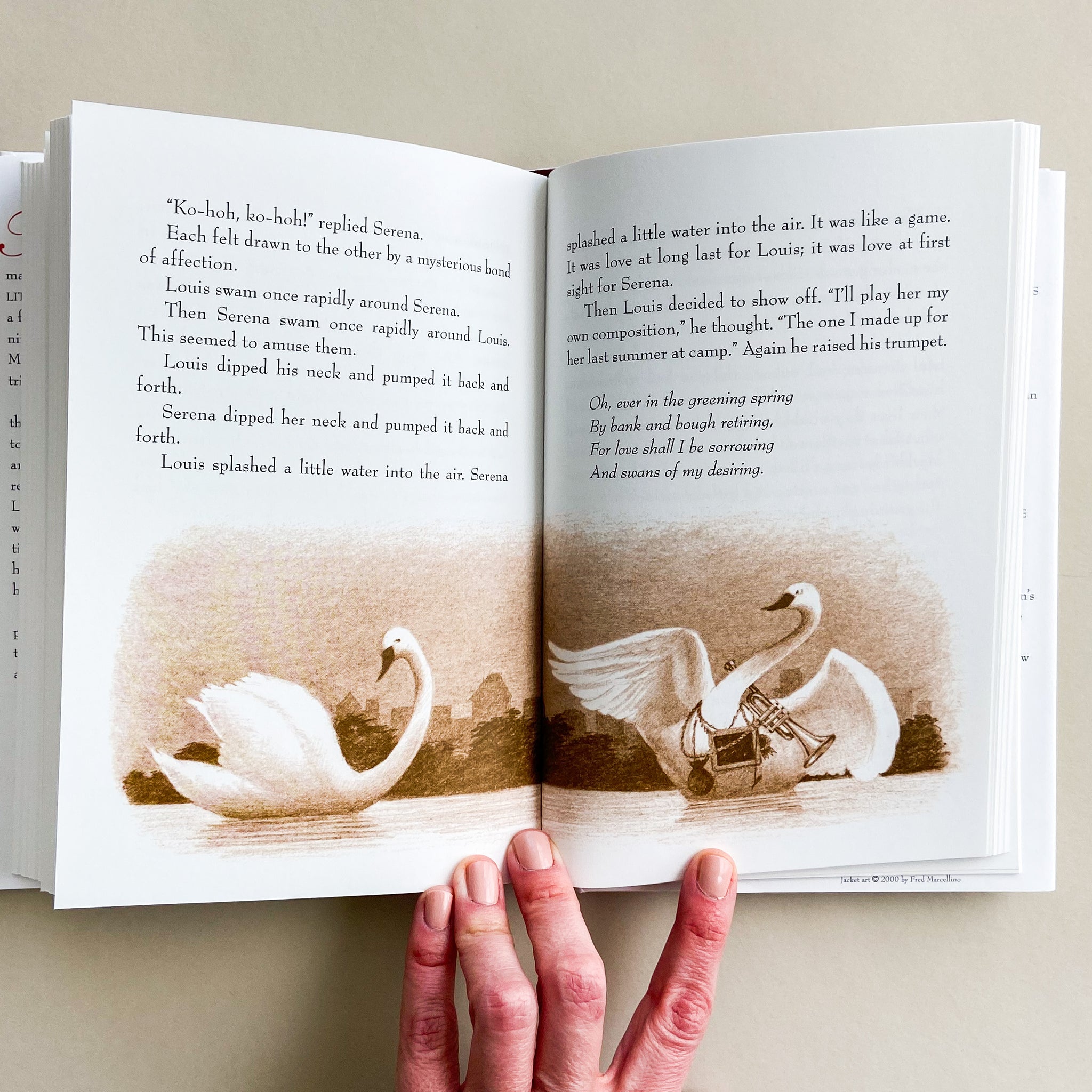

Imagine being a Trumpeter Swan who can't trumpet. It’s a biological disaster. For Louis, the protagonist of The Trumpet of the Swan, his lack of a voice isn't just a social awkwardness. It's an existential wall. He can't tell Serena, the swan of his dreams, how he feels. In the world of swans, if you can't make noise, you basically don't exist.

His father, the old cob, is one of the most interesting characters White ever wrote. He’s boastful. He’s dramatic. He speaks in these grand, sweeping sentences that feel like they belong in a Shakespearean play. He’s also a thief. To "fix" his son’s problem, he crashes through the window of a music store in Billings, Montana, and steals a brass trumpet. It’s a crime of passion. He wants his son to have a voice so badly that he’s willing to sacrifice his honor. This creates a massive weight of debt for Louis. Louis doesn't just want to play music; he wants to pay back the store owner. He wants to be "clean."

That’s a heavy theme for a kids' book. Debt. Honor. Redemption. It’s not just about a bird blowing a horn. It's about the moral cost of our advantages. Louis spends the rest of the book working jobs—at a summer camp, in a zoo—just to earn enough money to make things right. He carries a slate and a chalk pencil around his neck to communicate with humans. It’s clumsy. It’s awkward. But he makes it work.

Why the Critics Were Wrong About Louis

When the book first came out, some critics weren't sure what to make of it. John Updike, writing for The New Yorker, famously gave it a bit of a lukewarm reception compared to White’s earlier masterpieces. People thought it was too episodic. They thought the logic of a swan playing a trumpet was too far-fetched, even for a fable.

📖 Related: Cast of Buddy 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

But they missed the point.

The charm of The Trumpet of the Swan is exactly that grounded absurdity. White describes the mechanics of how a swan would actually press the valves of a trumpet (he uses his third toe) with the same precision he used to describe a spider spinning a web. He treats the impossible as a technical challenge. It’s that E.B. White magic. He doesn't talk down to kids. He assumes they’ll understand that if a swan wants to play "Cradle Song" at a summer camp in Ontario, he’s going to need a way to manipulate the spit valve.

Real experts in children’s literature, like Peter Neumeyer, who spent years analyzing White’s letters and drafts, have pointed out how much of White’s own life is in here. White loved the natural world. He spent time at Belgrade Lakes in Maine. You see that reflected in the character of Sam Beaver, the boy who becomes Louis’s friend and confidant. Sam is the bridge between the human world and the wild world. He’s the one who asks his diary questions like, "Why does a red-winged blackbird have red wings?" He’s a kid who notices things.

The Real Locations Behind the Story

White didn't just make up these settings. They’re real places that you can still visit, and they carry the DNA of the book.

- The Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge: This is in Montana. It’s where the cob steals the trumpet. It’s a real stronghold for Trumpeter Swans, which were once nearly extinct.

- Philadelphia: Louis plays for the Philadelphia Orchestra. Well, sort of. He plays at the zoo and becomes a local celebrity. White captures the vibe of the city in the 60s perfectly.

- The Ritz-Carlton, Boston: Louis actually stays here. He orders watercress sandwiches. The hotel has leaned into this history for years, often hosting events that celebrate the book.

The Music and the Message

Music is the heartbeat of this story. Louis doesn't just play noise; he plays jazz, classical, and bugle calls. He learns the "Taps" and "Reveille." He learns that music is a universal language that can bridge the gap between species. When he plays for Serena, he isn't just showing off a skill. He's revealing his heart.

👉 See also: Carrie Bradshaw apt NYC: Why Fans Still Flock to Perry Street

There's a specific scene where Louis is at Camp Kookooskoos. He’s the camp bugler. He earns a silver medal for saving a boy from drowning. But the real victory is the music. It’s the way the sound carries over the water at night. Anyone who has ever been to the woods knows that sound. It’s haunting. White captures that stillness better than almost anyone.

Some people find the ending a bit strange. Louis eventually returns to the wild. He pays off the debt. He has a family. But he keeps the trumpet. It’s a part of him now. He’s a hybrid creature—half wild swan, half refined musician. It’s a metaphor for the way education and art change us. Once you’ve learned to play the trumpet, you can never just be a regular swan again. You’re something new. Something more complex.

Things You Might Have Forgotten

If it’s been twenty years since you read it, some details probably slipped your mind. Like the fact that the cob gets shot in the butt while trying to return the money. It’s a weirdly violent moment in a gentle book. Or the fact that Louis has to deal with the bureaucracy of the Philadelphia Zoo, which wants to keep him captive.

White explores the idea of freedom versus security. The zoo offers Louis a pampered life. Plenty of food. No predators. A nice pond. But he chooses the wild. He chooses the "vulnerable" life because that’s where his soul is. It’s a heavy lesson for a kid, but an important one. Security is a cage, even if the bars are made of gold (or watercress sandwiches).

The book also touches on the environmental reality of the time. Trumpeter Swans were a success story of the early conservation movement. By including them, White was subtly pointing toward the importance of preserving wild spaces. He wasn't a "preachy" writer, but his love for the earth is on every page. He makes you care about a bird's ability to fly north for the winter.

✨ Don't miss: Brother May I Have Some Oats Script: Why This Bizarre Pig Meme Refuses to Die

Actionable Takeaways for Readers Today

If you’re looking to revisit this classic or introduce it to someone else, don't just read the words. Lean into the experience.

- Listen to the calls: Go on YouTube and look up actual Trumpeter Swan recordings. They don't sound like ducks. They sound like French horns. Once you hear the real thing, the book makes way more sense.

- Visit a refuge: If you’re ever in Montana or the Pacific Northwest, look for these birds. They are massive. Seeing a 30-pound bird with an eight-foot wingspan changes your perspective on Louis’s struggle.

- Check out the 2001 movie (with caution): There’s an animated film. It features Jason Alexander and Mary Steenburgen. Honestly? It’s... okay. It takes some liberties. It doesn't quite capture White’s dry wit, but it’s a fun entry point for younger kids who might find the book’s pacing a bit slow.

- Read the letters: If you really want to understand the "why" behind the book, pick up Letters of E.B. White. You’ll see his obsession with nature and his meticulous process for getting the details of Louis's life just right.

The Trumpet of the Swan isn't a perfect book, but that’s why it’s great. It’s messy and adventurous and deeply human. It reminds us that even if we feel like we’re missing something fundamental—a voice, a talent, a sense of belonging—we can find a workaround. We can find our own "trumpet."

To get the most out of this story, try reading it aloud. E.B. White wrote for the ear. The cadences of the old cob’s speeches are meant to be performed. You’ll find yourself slowing down, enjoying the rhythm of the sentences, and realizing that Louis’s silence was never actually a silence at all. It was just a different kind of music.

If you’re planning a trip to any of the locations mentioned, check the seasonal migration patterns first. Trumpeter Swans are most active in the winter months in places like the Skagit Valley or the tri-state area of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Seeing them in the wild is the best way to bring the legacy of Louis to life.