You probably think you know the deal with the three little pigs. They build some houses, a wolf comes around with a serious breathing problem, and the one who worked the hardest wins. It's the ultimate lecture on the "Protestant work ethic" disguised as a bedtime story. But honestly, the true story of the three little pigs is way messier, older, and darker than the Disney version most of us grew up with.

The story isn't just about construction materials. Not really.

It’s an oral tradition that was bouncing around for centuries before anyone bothered to write it down. When James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps finally put it into The Nursery Rhymes of England around 1843, he wasn't trying to sell toys or theme park tickets. He was capturing a piece of English folklore that was, frankly, kind of brutal.

The Version Your Parents Didn't Tell You

Let’s get one thing straight: in the original English folk versions, there were no "escaped" pigs.

In the story most of us know today—popularized largely by the 1933 Disney Silly Symphony—the first two pigs run away to their brother's brick house after their flimsy homes get leveled. They survive. They learn a lesson. Everyone is happy. But in the true story of the three little pigs found in Joseph Jacobs' English Fairy Tales (1890), the stakes were significantly higher.

The wolf eats them.

He doesn't just scare them. He devours the first two pigs immediately after their houses fall. There’s no running away. There’s no second chance. It’s a survival story, not a "try again tomorrow" story. This wasn't meant to be "nice." Folklorists like Andrew Lang have pointed out that these stories were originally tools for teaching children about the very real dangers of the world, where mistakes often had permanent consequences.

Why Straw and Furze?

We always laugh at the first two pigs for being lazy. But if you look at the historical context of rural England, building with straw or "furze" (basically gorse or brushwood) wasn't just laziness. It was what poor people actually used.

Straw was a byproduct of the harvest. It was cheap. Furze was readily available on common land. Bricks? Bricks required a kiln, fuel, and specialized labor. By building with bricks, the third pig wasn't just "hardworking"—he was wealthy. He had capital. The story is a subtle nod to the class structures of the 19th century, though most people just see it as a lesson in manual labor.

✨ Don't miss: Chase From Paw Patrol: Why This German Shepherd Is Actually a Big Deal

What Really Happened With the Wolf?

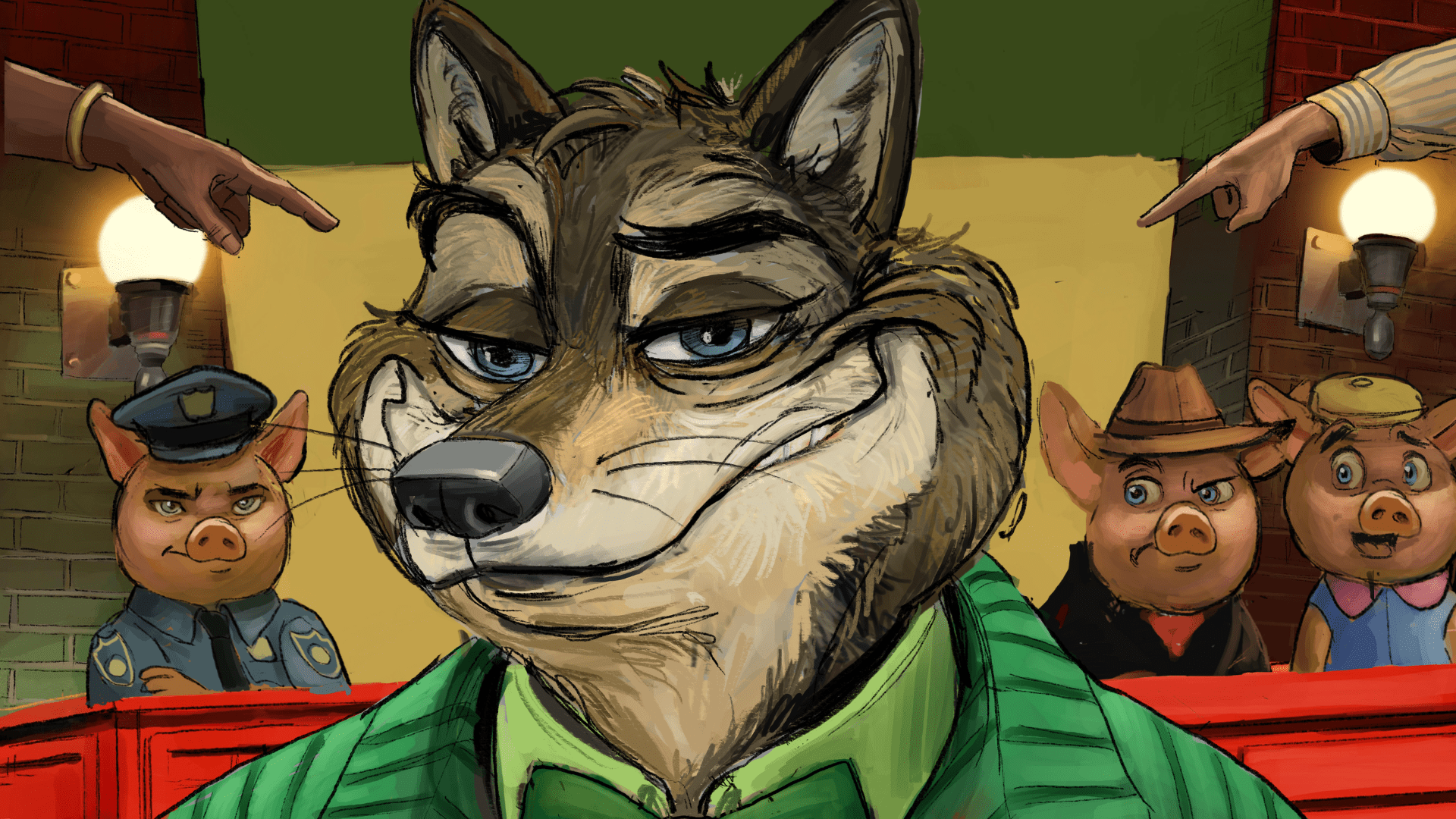

The wolf is the villain, obviously. But in the true story of the three little pigs, he’s not just a mindless beast. He’s a trickster.

Most people forget the "Turnip Incident."

In the Joseph Jacobs version, after the wolf fails to blow down the brick house, he doesn't immediately go for the chimney. Instead, he tries to lure the third pig out with "appointments." He tells the pig about a nice field of turnips at Mr. Smith's Home Farm and suggests they go together at six o'clock the next morning.

The pig, being smarter than your average swine, wakes up at five, gets the turnips, and is back home before the wolf even shows up. This happens again with apples and a trip to the fair.

It’s a battle of wits.

The wolf represents the "predatory stranger," a common trope in European folklore (think Little Red Riding Hood). The third pig doesn't just win because he built a strong wall; he wins because he is more cunning than his predator. He out-thinks the wolf at every turn.

The Gruesome End of the Big Bad Wolf

Disney had the wolf burn his tail on a pot of boiling water and run away into the woods. It's a classic "slapstick" ending.

The true story of the three little pigs is much more visceral.

🔗 Read more: Charlize Theron Sweet November: Why This Panned Rom-Com Became a Cult Favorite

When the wolf finally realizes he can’t out-talk or out-blow the pig, he climbs down the chimney. The pig has a giant pot of water boiling over the fire. He pulls the lid off at the exact moment the wolf falls in.

Then, the pig eats the wolf for supper.

Yes. The pig eats the wolf.

"Then the little pig put on the cover again, and supped him up, and lived happy ever after." — Joseph Jacobs, English Fairy Tales.

It’s a complete reversal of the food chain. The prey becomes the predator. This is a common theme in "Tale Type 124" (the international classification for this specific story type), where the underdog must go to extreme lengths to ensure their safety.

Where the Story Actually Came From

Folklorists have traced the roots of this story back much further than 19th-century England. While the "three pigs" version is the most famous, there are variations across the globe that use different animals.

In some Italian versions, there are three goslings. In others, there are kids (young goats). The core remains the same:

- Building homes of varying strength.

- A predator attempting to gain entry through physical force and deception.

- A final confrontation involving a chimney or a fire.

The most interesting thing is that the "three" in the story is a classic rule of three used in oral storytelling. It’s the perfect number for building tension. One is an accident, two is a pattern, three is a climax.

💡 You might also like: Charlie Charlie Are You Here: Why the Viral Demon Myth Still Creeps Us Out

Modern Interpretations and Subversions

Because the true story of the three little pigs is so ingrained in our psyche, authors have been messing with it for years.

You’ve probably heard of The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs! by Jon Scieszka. In that book, "A. Wolf" claims he just had a cold and was trying to borrow a cup of sugar. It’s a brilliant look at perspective and "unreliable narrators."

Then there’s the 1989 "Guardian" advert, which used the story to show how a news cycle can spin a story from multiple angles. It’s been used in psychology to discuss "delayed gratification" (the idea that putting in hard work now pays off later).

But all these modern takes rely on us knowing the "basic" version. And the "basic" version is actually the sanitized, 20th-century edit.

Why We Keep Telling It

The story sticks because it taps into a primal fear. The idea of "home" as a sanctuary is universal. When the wolf says, "I'll huff and I'll puff," he is threatening the one place where we are supposed to be safe.

It’s also about the transition from the "natural world" to the "civilized world."

Straw and sticks are natural. Bricks are man-made. The story argues that to survive the wild (the wolf), we must move away from the wild and embrace technology and permanence.

Actionable Insights from the Original Folk Tale

If you're looking for more than just a history lesson, the true story of the three little pigs actually offers some pretty solid life advice that goes beyond "work hard."

- Audit your "materials" frequently. Just because something is easy (like a straw-built project or a quick-fix solution) doesn't mean it will hold up under pressure. Ask yourself: "Will this survive a 'wolf' event?"

- Out-schedule your competition. The third pig didn't just have a better house; he got up an hour earlier than the wolf to get the turnips. Speed and timing are often more important than the quality of your "bricks."

- Don't rely on a single defense. The third pig had the brick house and the boiling pot and the wit to wake up early. He had layers of protection.

- Acknowledge the darker roots. When teaching or sharing stories, understanding the original context helps you appreciate the evolution of culture. The shift from "the wolf eats the pigs" to "the pigs live happily ever after" says a lot about how our views on childhood and safety have changed over 200 years.

To dig deeper into the history of these tales, check out the SurLaLune Fairy Tales archive or read the original Joseph Jacobs transcriptions. Understanding the origins of the true story of the three little pigs helps us see that these aren't just "kids' stories"—they are survival manuals from a much tougher era.