Maps lie. Well, they don't exactly lie on purpose, but they’ve been tricking your brain since elementary school. If you look at a standard classroom map, Greenland looks like a massive icy continent that could swallow Africa whole. In reality? Africa is fourteen times larger. This isn't a conspiracy; it's a math problem. Because the Earth is a sphere and paper is flat, you can’t stretch the surface without distorting something.

That’s where thetruesize.com comes in.

It’s a simple, web-based tool created by James Talmage and Damon Maneice. They launched it years ago, but it stays viral because the human brain is surprisingly stubborn about spatial awareness. You go to the site, type in a country, and suddenly you’re dragging a translucent outline of the United States over to Europe. You realize that the U.S. spans almost the entire continent. You drag the Democratic Republic of the Congo over to the UK and realize the UK is a tiny speck by comparison. It’s addictive. It's jarring. Honestly, it’s one of those rare corners of the internet that makes you feel smarter and dumber at the exact same time.

The Mercator Problem: Why Your Brain is Hardwired to Be Wrong

The culprit behind our collective confusion is the Mercator Projection.

Gerardus Mercator, a Flemish geographer, whipped this up in 1569. He wasn't trying to make Europe look more important, even if that was a nice side effect for the era's colonial powers. He was trying to help sailors. The Mercator projection is fantastic for navigation because it preserves "rhumb lines," meaning if you draw a straight line between two points on the map, that’s the actual compass bearing you need to sail.

But there’s a massive trade-off.

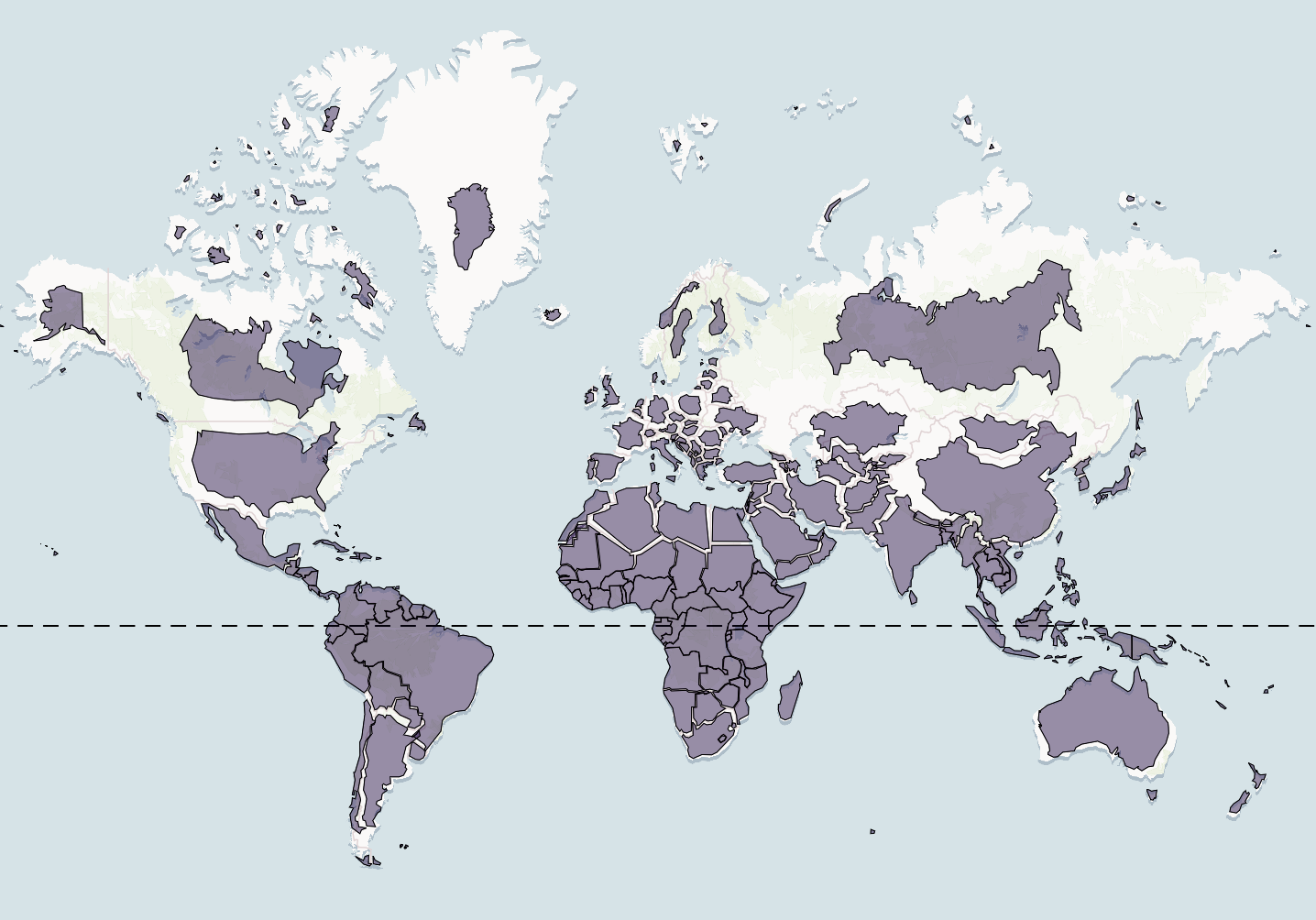

To keep those angles straight, the map stretches things the further you get from the equator. The poles become infinite. This is why Antarctica looks like a never-ending white shelf at the bottom of the map instead of a circular continent. It's why Canada looks like it owns half the planet. When you use thetruesize.com, you’re basically undoing 500 years of navigational distortion. The site uses a Google Maps API that adjusts the shape of the country as you move it north or south, showing you the "true" scale relative to its position on the globe.

👉 See also: When Were Clocks First Invented: What Most People Get Wrong About Time

Greenland vs. The World

Let's talk about Greenland. It’s the poster child for map distortion. On a Mercator map, it looks roughly the same size as Africa. If you take Greenland on thetruesize.com and drag it down to the equator, it shrinks. It shrivels. By the time you overlay it on Africa, you see it’s roughly the size of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It’s a large island, sure, but it’s not a continent-sized behemoth.

Conversely, look at Brazil. Brazil is freaking huge. On most maps, it looks big, but because it sits near the equator, it doesn't get the "Mercator stretch" that northern countries enjoy. When you drag Brazil up to Europe, it covers nearly the entire European Union. People don't realize this because our eyes are trained to value the North.

The Politics of Projection

Maps aren't just geography; they're power.

There has been a lot of academic debate—specifically from people like Arno Peters in the 1970s—suggesting that the Mercator projection creates a "Eurocentric" worldview. The argument is that by making northern, industrialized nations look larger, we subconsciously view them as more important. While Mercator was a math choice, the cultural impact is real. When you see Africa looking smaller than it is, you might underestimate its resources, its population, or its geopolitical weight.

Thetruesize.com actually democratizes this data. You don't need a PhD in cartography to see the reality. You just need a mouse.

Interestingly, some maps try to fix this. The Gall-Peters projection is an "equal-area" map. It shows countries in their correct size relative to each other, but it makes the continents look "stretched" vertically. It looks weird to us because we’re so used to the Mercator "look." Then there’s the Robinson projection or the Winkel Tripel (which National Geographic uses), which try to find a middle ground by distorting everything just a little bit so nothing looks too crazy.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Gun to Head Stock Image is Becoming a Digital Relic

But none of them are as visceral as dragging India over to Russia and realizing India is way bigger than you thought.

Why This Tool Still Matters in 2026

We live in a world of data, but we’re still remarkably bad at visualizing it. Thetruesize.com isn't just a toy for geography nerds; it’s a tool for perspective. In an era where global logistics, climate change, and migration are the biggest stories on Earth, knowing how big the "stage" actually is matters.

Consider China.

When you drag China over the United States, you see they are remarkably similar in landmass. But then you realize China has four times the population packed into that same space. Or look at Australia. On a map, it’s tucked away at the bottom. Drag it over Europe, and it stretches from London to Istanbul. It’s a continent-country that we often treat like a large island.

The site works because it’s tactile. You’re interacting with the distortion. You see the country shape-shift as it moves toward the poles. It’s a live demonstration of the "Tissot’s Indicatrix," which is the mathematical way cartographers show how much distortion exists at any given point on a map.

Technical Limitations of the Web Tool

Is it perfect? No. Thetruesize.com uses the Google Maps projection (Web Mercator), which is standard for almost all web maps. While it's great for dragging countries around, it still exists within a 2D browser. It can't perfectly replicate the experience of holding a physical globe. Also, the site focuses on landmass. It doesn't account for Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) or the underwater continental shelves that define a nation's actual reach.

🔗 Read more: Who is Blue Origin and Why Should You Care About Bezos's Space Dream?

But for a free tool? It’s unbeatable.

Using Geography to Kill Myths

There’s a common misconception that Russia is so big it could cover the entire world. Russia is huge—it’s the largest country by landmass, period. But Mercator makes it look like it’s 25% of the Earth's surface. When you pull Russia down to the equator on the site, it thins out significantly. It’s still massive, but you realize that the "Top of the World" distortion is doing a lot of the heavy lifting for its visual intimidation.

Then there’s the "Africa is Huge" realization.

You can fit the US, China, India, Japan, and most of Europe into Africa. People say that all the time, but seeing the outlines actually fit inside the African borders on your screen is a different kind of learning. It’s the "Aha!" moment that teachers dream about.

Actionable Ways to Use This Information

If you want to actually get some value out of this beyond just killing ten minutes at work, here’s how to apply this perspective:

- Travel Planning: Use the tool to compare your home state to a country you’re visiting. If you're from Texas and you're visiting France, dragging France over Texas shows you that you’re dealing with a much smaller area than you might have thought. It helps you understand travel times and scale.

- Education: If you have kids, don't just show them a map. Let them play the "Size Guessing Game" on the site. Ask them which is bigger: Indonesia or the USA? (Indonesia is surprisingly wide; it spans roughly the same distance as the contiguous US).

- News Consumption: Next time you see a geopolitical story about a conflict or a border dispute, check the actual size of the region. We often lose the sense of scale when looking at zoomed-in news graphics.

- Design and Presentation: If you’re a student or professional making a deck about global markets, don't use a standard Mercator map if you're trying to emphasize the importance of the Global South. It literally shrinks your subject matter.

The reality is that our world is a "complex" sphere that we keep trying to simplify. Thetruesize.com doesn't just show us countries; it shows us the limits of our own perspective. It reminds us that the way we see the world is often just a byproduct of the tools we use to measure it.

The next time you look at a wall map, remember that Greenland is just a normal-sized island, Africa is a giant, and your eyes are being lied to by a 16th-century sailor’s cheat sheet. Go play with the tool. It’s the easiest way to realize how much you still have to learn about the planet we live on.