July 16, 1945. 5:29 AM. Somewhere in the middle of the New Mexico desert, a group of exhausted, terrified, and brilliant scientists held their breath. They were about to change everything. Forever.

Most people think they know the story of the atom bomb first test, often referred to by the code name Trinity. We’ve seen the grainy black-and-white footage of the mushroom cloud. We've heard the haunting "Destroyer of Worlds" quote from J. Robert Oppenheimer. But the actual reality on the ground at the Jornada del Muerto—the "Journey of the Dead Man" desert—was far more chaotic, weird, and dangerously uncertain than the history books usually let on. It wasn't just a clinical experiment; it was a high-stakes gamble that almost didn't happen because of a thunderstorm.

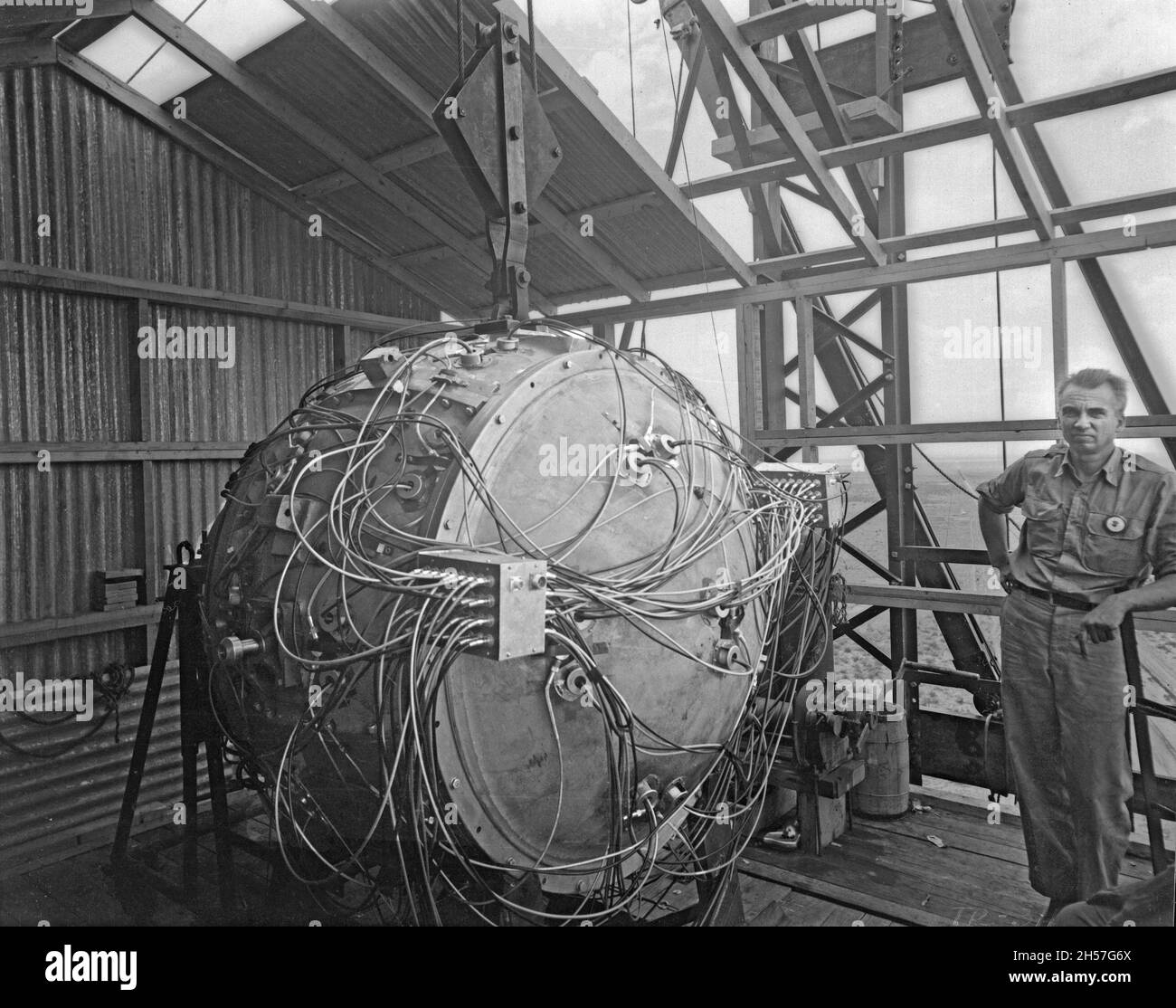

The Gadget and the Gamble

The device itself wasn't called a "bomb" by those who built it. They called it "The Gadget." It was a five-ton sphere of steel and wires, looking more like a weird steampunk art project than the most destructive weapon in human history.

Inside that sphere sat a core of plutonium, roughly the size of a grapefruit. The physics was theoretical. The stakes were absolute. Honestly, some of the scientists weren't even sure it would work. Enrico Fermi, a Nobel Prize winner, was actually taking bets on whether the explosion would ignite the Earth's atmosphere and incinerate the entire planet. He wasn't joking. It was a dark, nervous humor that permeated the camp. Imagine standing in the dark, wondering if your next button press will literally end the world.

The atom bomb first test was the culmination of the Manhattan Project, a $2 billion (in 1940s money) secret endeavor that employed over 100,000 people. Yet, the final success came down to a few dozen people lying face down in the dirt, 10 miles away from a 100-foot steel tower.

✨ Don't miss: Neil Armstrong: What Really Happened With the First Man on the Moon

Why the Weather Almost Ruined Everything

You’d think for a multi-billion dollar project, they’d have a better handle on the weather.

They didn't.

A massive thunderstorm rolled in on the night of July 15. Lightning was striking all around the steel tower holding "The Gadget." This was a nightmare. If lightning hit the tower, it could have triggered the conventional explosives used to compress the plutonium core. It wouldn't have been a nuclear blast, but it would have scattered radioactive material across the desert and ruined years of work.

General Leslie Groves, the military head of the project, was furious. He threatened the project's meteorologist, Jack Hubbard, telling him that if the forecast was wrong, he’d "better find another job." Hubbard held his ground. He predicted a window of clear weather at dawn.

The rain stopped. The clouds parted. The countdown began.

The Moment of Ignition at the Trinity Site

When the clock hit zero, the world didn't just see a light. They felt a heat that shouldn't exist.

The flash was brighter than a dozen suns. People 200 miles away saw the sky light up. A forest ranger in Arizona thought he saw a plane crash. A blind girl in Albuquerque, over 150 miles away, asked "What's that flash?" because she felt the heat on her skin. That’s the kind of power we’re talking about.

The desert sand turned into glass. This wasn't just any glass; it was a sea of shimmering, jade-green radioactive crystals later named "Trinitite."

The Real Aftermath Nobody Talks About

The heat was so intense it vaporized the steel tower. Gone. Just a few stumps of reinforced concrete remained.

But here’s the thing: the scientists were actually relieved. It worked. Kenneth Bainbridge, the man in charge of the test, famously turned to Oppenheimer and said, "Now we are all sons of bitches." It’s a raw, honest moment that cuts through the patriotic polish often applied to this era. They knew what they had unleashed.

The radioactive fallout was another story. They didn't really understand how far it would travel. The cloud drifted northeast, dropping radioactive dust over towns like Bingham and Roswell. People saw their livestock getting weird burns. Their hair fell out in patches. The government didn't tell them what happened for years. They just said a "remotely located ammunition dump" had exploded.

Technical Details of the Trinity Device

If you look at the mechanics, the atom bomb first test was incredibly complex. It used an "implosion-type" design.

- A plutonium core (the "Pit") was placed in the center.

- It was surrounded by high-explosive lenses designed to fire at the exact same microsecond.

- This created a shockwave that compressed the plutonium to a critical mass.

- $E=mc^2$ took over.

The yield was roughly 21 kilotons of TNT. To put that in perspective, the conventional bombs used in WWII usually carried a few tons of explosives. This was a jump of several orders of magnitude in a single morning.

Why the First Atom Bomb Test Still Matters Today

We live in the shadow of Trinity. It wasn't just a military milestone; it was the birth of the Anthropocene—a new geological epoch where humans have the power to permanently alter the Earth's biology and geology.

The atom bomb first test proved that we could manipulate the very fabric of matter. It led to nuclear power, which provides a huge chunk of carbon-free energy today. It led to nuclear medicine, which treats cancer. But it also started an arms race that brought us to the brink of extinction during the Cold War.

When you look at the Trinity site today (it's open to the public only two days a year), it's a quiet, eerie place. There's a simple lava-rock obelisk marking Ground Zero. It doesn't look like much. But it’s the spot where the modern world began.

Misconceptions to Clear Up

- It wasn't the Hiroshima bomb: The Trinity test used plutonium. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima, "Little Boy," used uranium-235 and was a completely different "gun-type" design. The military was so confident the uranium bomb would work that they didn't even bother testing it before using it.

- The scientists weren't all "pro-bomb": Many, like Leo Szilard, tried to stop the use of the weapon against cities before it was even tested.

- The "Destroyer of Worlds" quote: Oppenheimer didn't say it out loud at the moment of the blast. He later recalled that the line from the Bhagavad Gita came to his mind. In the moment, he mostly just looked relieved that the thing didn't fizzle.

Actionable Insights for History and Tech Buffs

If you're fascinated by the Trinity test, don't just read the Wikipedia page. There are better ways to grasp the weight of this event:

- Visit the Site: The Trinity Site is open to the public on the first Saturday of April and October. It is located on the White Sands Missile Range. Wear closed-toe shoes; you can still find tiny bits of Trinitite (though it's illegal to take it).

- Read the Sources: Check out American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin for the human side, or The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes for the technical and political grit.

- Understand the Fallout: Research the "Downwinders." These are the families in New Mexico who were affected by the radiation from the 1945 test. Their story is often skipped in standard history books, but it’s crucial for a full understanding of the event's cost.

- Museums: If you can't get to the desert, the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History in Albuquerque has full-scale casings of the bombs and incredible archives from the Manhattan Project.

The Trinity test wasn't just a "win" for science. It was a moment of profound loss and terrifying gain. It showed us that we are capable of extraordinary genius and catastrophic shortsightedness, often at the exact same time.