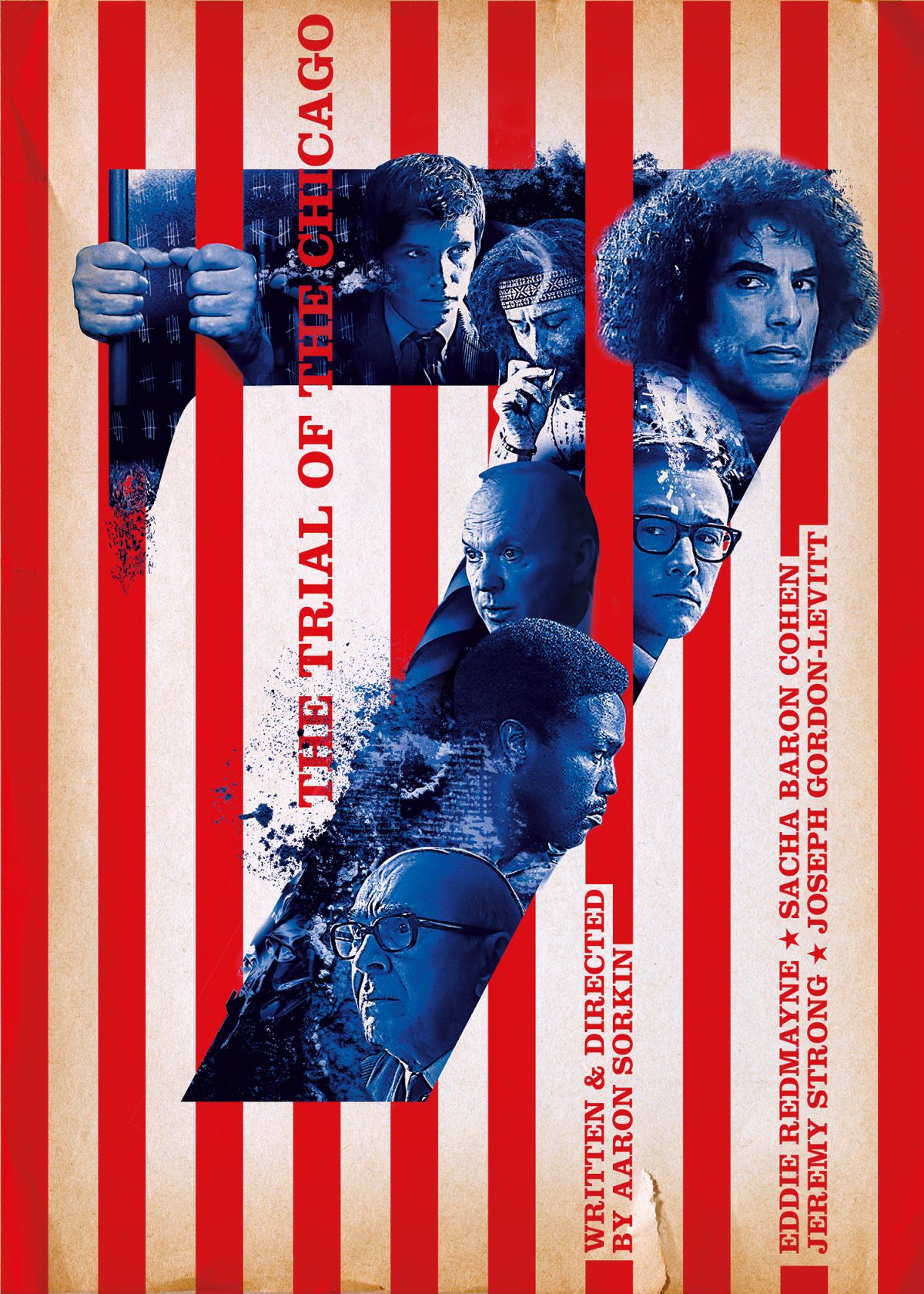

You've probably seen the Aaron Sorkin movie. It’s flashy, fast-talking, and filled with Sacha Baron Cohen doing a surprisingly decent Abbie Hoffman impression. But Hollywood has a way of smoothing out the jagged edges of history to make a better script. The real trial of the Chicago 7 wasn't just a snappy legal drama; it was a messy, chaotic, and frankly terrifying collision between the American counterculture and a judicial system that was losing its mind.

It started with the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Thousands of young people descended on Chicago to protest the Vietnam War. They met a wall of police officers. What followed was what the Walker Report later called a "police riot." But the government didn't prosecute the police. Instead, the newly inaugurated Nixon administration decided to make an example of the organizers. They used the Anti-Riot Act—a piece of legislation tacked onto the Civil Rights Act of 1968—to claim these eight men had crossed state lines to incite a riot.

Wait, eight?

Yeah, it was originally the Chicago 8. Bobby Seale, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party, was the eighth man. His treatment is the part that usually makes people's blood run cold when they look back at the transcripts.

The Judge Who Turned a Trial Into a War Zone

Julius Hoffman was seventy-three years old, tiny, and incredibly hostile. He wasn't related to Abbie Hoffman, though Abbie joked about being his "illegitimate son" throughout the proceedings. Judge Hoffman seemed to loathe the defendants from the moment they walked in. He denied their motions, insulted their lawyers, and eventually did the unthinkable.

Bobby Seale didn't have his lawyer. Charles Garry, Seale's preferred counsel, was undergoing gallbladder surgery. The judge refused to delay the trial. When Seale tried to represent himself—a basic constitutional right—Hoffman said no. Seale kept protesting. He called the judge a "fascist," a "pig," and a "racist."

In response, Judge Hoffman ordered the court marshals to bind and gag him.

👉 See also: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

For several days of the trial of the Chicago 7 (still eight at this point), a Black man sat in an American courtroom chained to a chair with a cloth stuffed in his mouth. It’s an image that sits heavy in the gut. Even the other defendants, who were mostly white radicals, were horrified. Eventually, the judge realized this was a PR nightmare, declared a mistrial for Seale, and sentenced him to four years for contempt. Then there were seven.

Meet the "Conspirators" (Who Barely Liked Each Other)

The prosecution's biggest hurdle was proving a conspiracy. To have a conspiracy, people usually have to agree on a plan. These guys? They could barely agree on what to eat for lunch.

- Tom Hayden and Rennie Davis: The "serious" organizers from SDS (Students for a Democratic Society). They wanted disciplined political pressure.

- Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin: The Yippies. They wanted to levitate the Pentagon and nominate a pig named Pigasus for president.

- David Dellinger: A middle-aged, staunch pacifist who had been protesting since World War II.

- John Froines and Lee Weiner: Two academics who were basically wondering why they were even there. They were eventually acquitted of the main charges.

The defense was led by William Kunstler and Leonard Weinglass. Kunstler became a folk hero during this trial, largely because he stopped acting like a traditional lawyer and started acting like a participant in the movement. He shouted back. He leaned into the absurdity.

The Absurdity as a Legal Strategy

If the government was going to turn the law into a theater of the absurd, the defendants decided they would be the best actors on stage.

Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin once showed up to court wearing judicial robes. When the judge told them to take them off, they did—only to reveal Chicago police uniforms underneath. They blew kisses to the jury. They brought in "expert witnesses" like beat poet Allen Ginsberg, who chanted "Om" in the witness stand until the judge almost had an aneurysm.

It sounds funny, but the stakes were deadly. The country was tearing itself apart over Vietnam. Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy had just been assassinated the year before. The trial of the Chicago 7 was the focal point for every ounce of rage in the American psyche.

The prosecution, led by Tom Foran and Richard Schultz, tried to paint the defendants as dangerous revolutionaries who wanted to destroy the American family. They focused heavily on the "obscene" language used by the protesters. It was a classic generational divide: the Greatest Generation vs. the Baby Boomers, played out in a wood-paneled room in Illinois.

✨ Don't miss: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

The Verdict and the Fallout

After months of testimony, the jury came back with a split decision. They acquitted all seven of conspiracy. That was a huge blow to the government. However, they found five of them (Dellinger, Davis, Hayden, Hoffman, and Rubin) guilty of crossing state lines with the intent to incite a riot.

But Judge Hoffman wasn't done.

Before anyone could leave, he slapped the defendants and their lawyers with nearly 175 counts of criminal contempt. He was handing out years of prison time for things like "smiling" or "arguing a motion too long." Kunstler was sentenced to over four years just for being an effective (and annoying) lawyer.

The whole thing was a mess.

Naturally, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals eventually threw almost all of it out. They cited Judge Hoffman's "deprecatory and often antagonistic attitude" toward the defense. They also found out the FBI had been bugging the defense lawyers' offices. A total mistrial of justice from start to finish.

Why This Still Keeps Historians Up at Night

The trial of the Chicago 7 remains a Rorschach test for how you view the law.

Was it a necessary crackdown on violent radicals who put a city at risk? Or was it a politically motivated witch hunt designed to silence dissent? Most modern legal scholars lean toward the latter. The use of the "Rap Brown Law" (the anti-riot statute) was seen by many as a direct attack on the First Amendment. It was a way to hold leaders responsible for the actions of thousands of people they couldn't possibly control.

🔗 Read more: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

Interestingly, the trial changed the defendants in different ways. Tom Hayden went into mainstream politics and married Jane Fonda. Jerry Rubin became a multimillionaire businessman on Wall Street in the 80s (the ultimate "Yippie to Yuppie" pipeline). Abbie Hoffman stayed a radical until the end, eventually taking his own life in 1989.

Lessons You Can Actually Use

Understanding this trial isn't just about trivia; it's about spotting the patterns of how power reacts when it's scared.

1. Watch the "Aggravator"

In legal settings or even corporate disputes, the person who stays calm usually wins the long game. The Chicago 7 won in the court of appeals because Judge Hoffman lost his cool. His bias was so documented that the convictions couldn't stand. If you're ever in a high-stakes conflict, let the other side be the one to overreach.

2. The Difference Between Theater and Substance

The Yippies used theater to gain attention, but it was the SDS's organizational "substance" that actually moved the needle on anti-war sentiment. In your own projects, stunts get you a headline, but boring organization gets you a result.

3. Recognize Legal "Overreach"

The conspiracy charge was the government's biggest mistake. By trying to prove a giant, interconnected plot, they made their case fragile. When you're trying to prove a point—whether in a debate or a business proposal—stick to the strongest, most direct facts. Don't try to weave a complex web that one missing thread can unravel.

If you want to dig deeper into the actual primary sources, the Chicago Historical Society holds a massive archive of the transcripts. Reading the actual words spoken in that room is far more surreal than any movie could ever portray. You'll see a system that was, for a brief moment, completely unhinged by the sight of long hair and the sound of "Omm."

To truly understand the American 1960s, you have to look past the Woodstock posters and look directly at the chains on Bobby Seale's chair. That is where the era's true story was told.

Next Steps for the History Buff:

- Read the Transcripts: Seek out "The Tales of Hoffman," a condensed version of the trial transcripts edited by Mark L. Levine. It’s wilder than the movie.

- Analyze the Anti-Riot Act: Research how 18 U.S.C. § 2101 is still applied today in federal cases involving civil unrest.

- Compare the Media Coverage: Use the New York Times digital archives to see how the "establishment" press reported the trial versus underground newspapers like the Chicago Seed at the time.