History is messy. It isn't just a collection of dates in a dusty textbook; it’s a series of high-stakes gambles where people often lose their heads. Literally. If you think modern politics is a circus, the trial of Louis XVI makes today's headlines look like a quiet afternoon tea. In late 1792, the French Revolution had reached a boiling point, and the man who used to be the absolute authority in the country was sitting in a courtroom—or rather, a chaotic hall full of angry revolutionaries—defending his life.

He wasn't King Louis anymore. To the National Convention, he was just "Citoyen Louis Capet."

Why the Trial of Louis XVI Was Never Going to Be Fair

Let’s be real for a second. The moment the Monarchy was abolished in September 1792, Louis was a dead man walking. The revolutionaries didn't just want him gone; they needed him to be guilty to justify the entire Revolution. If the King was innocent, then the Revolution was a crime. That's a heavy burden for any legal system to carry.

The legal basis for the trial of Louis XVI was shaky at best. The 1791 Constitution actually stated that the King’s person was "inviolable." Basically, he had legal immunity. But the Jacobins, led by the fiery Maximilien Robespierre and the ruthless Saint-Just, didn't care about technicalities. Saint-Just famously argued that "no one can reign innocently." He believed that being a king was, in itself, a crime against the people.

It was a total circus.

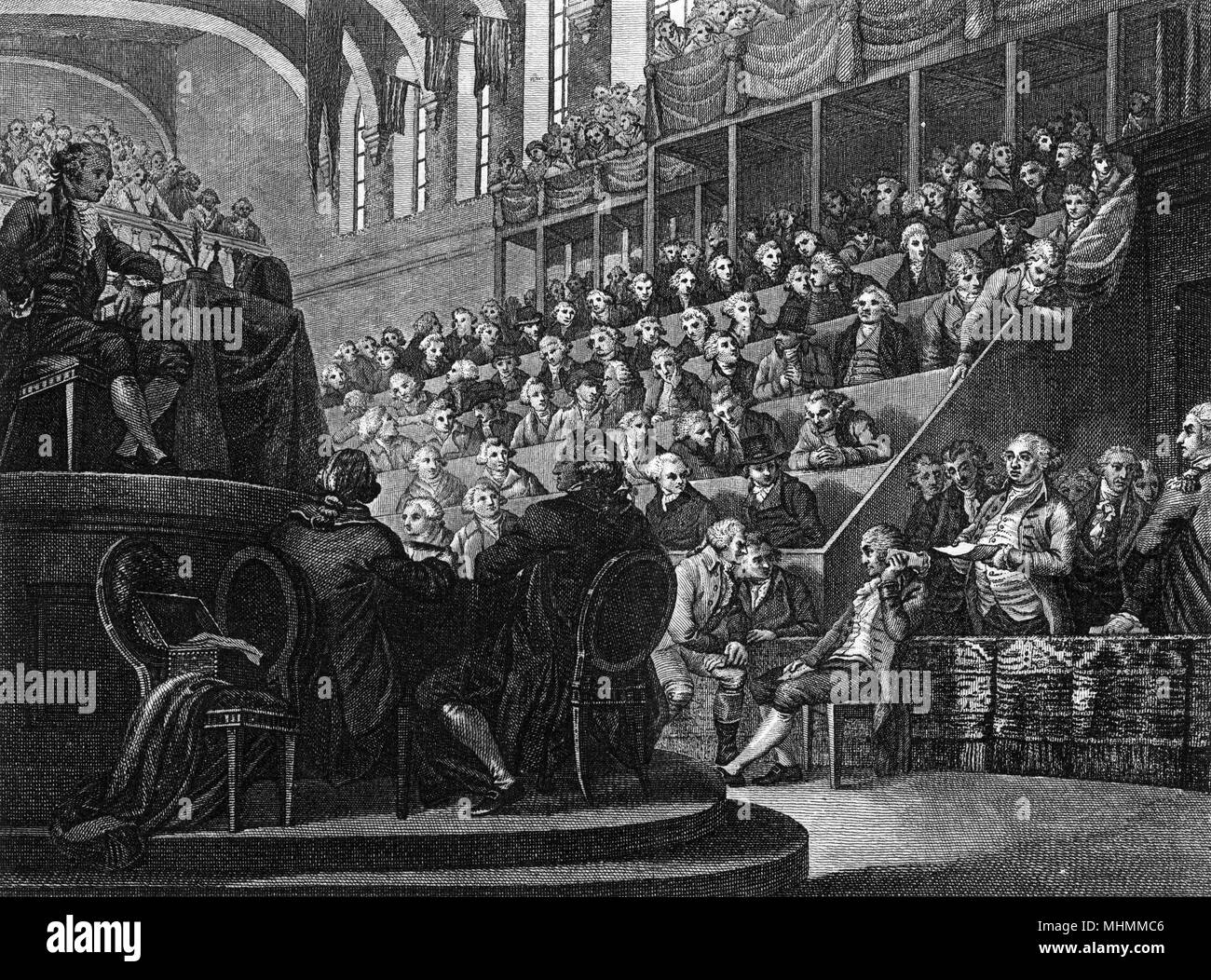

The trial took place at the Salle des Machines in the Tuileries. Imagine a cramped, dimly lit room packed with delegates who were exhausted, caffeinated on the 18th-century equivalent of espresso, and terrified of looking "soft" on royalty. There was no independent judge. The same people who accused him—the deputies of the National Convention—were also the jury and the judges.

The Smoking Gun: The Armoire de Fer

You can't have a good trial without a "gotcha" moment. For Louis, that moment came when a secret wall safe was discovered at the Tuileries Palace. Known as the Armoire de Fer (the Iron Chest), it contained correspondence that proved Louis was communicating with foreign powers and exiled nobles.

✨ Don't miss: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

Was he plotting to crush the Revolution with the help of Austria and Prussia?

Probably.

But Louis argued he was just trying to navigate a situation where his family's lives were constantly threatened. From a modern legal perspective, the evidence was damning, but it was also messy. Some of the documents were unsigned. Others were vague. But in the court of public opinion, the "Iron Chest" was the nail in the coffin. It made Louis look like a traitor who was inviting foreign armies to slaughter his own people.

The Charges and the Defense

The Convention hit Louis with 33 specific charges. They ranged from the suspension of the Estates-General to the "massacre" at the Champ de Mars (which he actually had little to do with).

Louis actually did something surprising. He fought back. He chose three lawyers to defend him: François Denis Tronchet, Guillaume-Chrétien de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, and Raymond Desèze. Malesherbes was particularly brave; he was an old man who knew that defending the King would likely lead to his own execution. It did.

Desèze gave a marathon speech on December 26. He was eloquent. He pointed out the absurdity of the trial. "I look for judges among you," he told the Convention, "but I see only accusers."

🔗 Read more: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

It was a brilliant defense. It changed almost nobody's mind.

The Vote: Life, Death, and the "Appeals to the People"

The voting process was an absolute nightmare. It lasted for days. Each of the 749 deputies had to stand up, walk to the podium, and announce their vote out loud in front of a gallery filled with screaming, bloodthirsty spectators. Talk about peer pressure.

There were four main questions put to the Convention:

- Is Louis guilty? (Almost everyone said yes).

- Should there be a national referendum to decide his fate? (This was a Girondin tactic to save him; it failed).

- What should the punishment be?

- Should there be a stay of execution?

The vote for death was incredibly close. Some records say it passed by a single vote, though the official count was 387 to 334 (with some nuances regarding conditional votes). Even Louis's own cousin, Philippe Égalité, voted for his death. When Louis heard that, he was reportedly more hurt by his cousin's betrayal than by the sentence itself.

January 21, 1793: The End of an Era

Execution day was cold. Louis woke up at 5:00 AM, heard Mass, and then was driven through the foggy streets of Paris in a carriage. He wasn't allowed to use the traditional royal coach. He showed a surprising amount of dignity.

At the Place de la Révolution (now the Place de la Concorde), he tried to speak to the crowd. He said, "I die innocent of all the crimes imputed to me..." but the Santerre (the commander of the National Guard) ordered a drum roll to drown out his voice.

💡 You might also like: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

The blade fell at 10:22 AM.

The trial of Louis XVI wasn't just about one man. It was the moment the "Old Regime" died. Once you kill a king, there’s no going back. It signaled the start of the Reign of Terror, where the revolution began devouring its own.

What This Means for History Buffs Today

If you're looking into this for a project or just because you’re a history nerd, don't just look at the verdict. Look at the political factions. The Girondins (the moderates) and the Montagnards (the radicals) weren't just arguing about Louis; they were fighting for the soul of France.

Common Misconceptions:

- Louis was a bumbling idiot: Not really. He was highly educated and spoke several languages. He was just indecisive and stuck in a system that was failing.

- The trial was a legal process: It was a political act. It followed the form of a trial, but the outcome was largely predetermined.

- Everyone hated him: Not true. Large parts of rural France remained loyal to the King and the Church, leading to brutal civil wars like the uprising in the Vendée.

How to Dive Deeper into the Revolutionary Period

If you want to understand the trial of Louis XVI better, you should look into the primary sources. Reading the actual transcripts of the Convention debates shows how terrified these men were. They weren't just building a new world; they were running for their lives.

- Visit the Archives Nationales: If you're ever in Paris, they hold the original documents from the Iron Chest.

- Read "The Twelve Who Ruled" by R.R. Palmer: It gives the best context for the Committee of Public Safety and why the King had to die in their eyes.

- Analyze the 1791 Constitution: Contrast the legal protections Louis was supposed to have with how the trial actually played out.

- Compare the trial to Charles I: Look at the English Civil War. The parallels are eerie, and the French revolutionaries were consciously trying to avoid (or mimic) the English example.

The trial remains a polarizing moment. Was it a necessary step toward democracy, or a judicial murder that paved the way for a dictator like Napoleon? Most historians agree it was a bit of both. It proved that in times of extreme crisis, the law often bows to the will of the loudest voices in the room.

Understanding this event helps make sense of every revolution that followed. It’s the ultimate case study in what happens when the social contract is completely torn up and rewritten in blood.