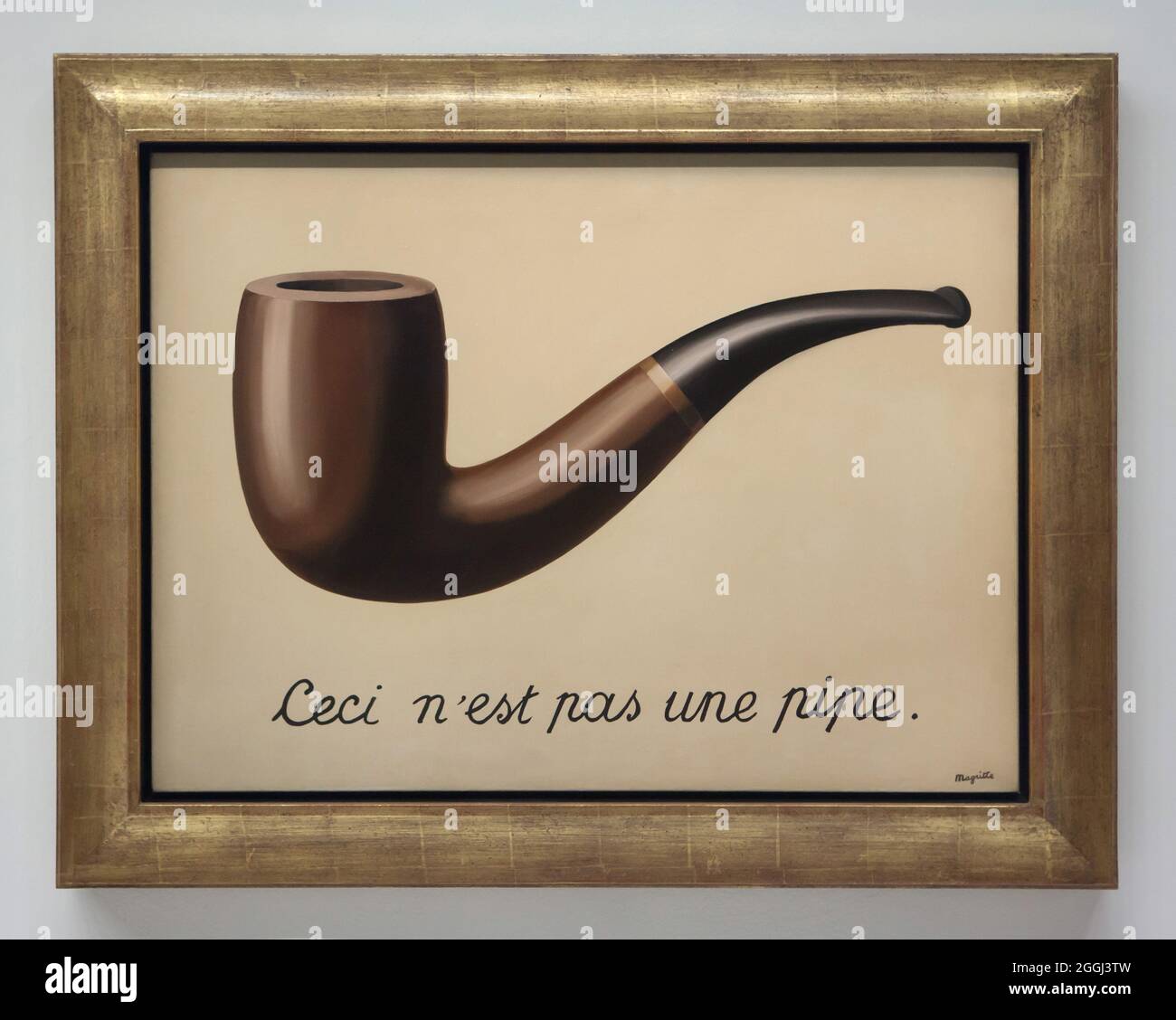

It is a pipe. Except, honestly, it isn't.

When René Magritte painted a realistic, almost commercial-looking tobacco pipe and then meticulously lettered the words "Ceci n’est pas une pipe" underneath it, he wasn't trying to be a jerk. He wasn't even being particularly difficult. He was stating a cold, hard fact that most of us forget the second we open our eyes in the morning.

The painting is actually titled The Treachery of Images (La Trahison des images), created in 1929. It’s arguably the most famous prank in art history, but the punchline is a bit more serious than a simple "gotcha." If you think about it for more than two seconds, you realize Magritte was right. If he had written "This is a pipe," he would have been lying.

Why? Because you can’t stuff tobacco into a canvas. You can’t light a two-dimensional representation of wood and Bakelite. It’s paint. It’s oil on cloth. It’s a representation.

The Problem With Our Brains

Our brains are lazy. Evolutionarily, this makes sense. If you see a drawing of a lion, your brain should probably register "lion" pretty fast, even if it's just ink on paper. But Magritte wanted to disrupt that shortcut. He was part of the Surrealist movement, a group of artists and thinkers like Salvador Dalí and André Breton who were obsessed with the subconscious and the weird gaps between reality and perception.

Magritte was different from Dalí, though. He didn't paint melting clocks or nightmare landscapes. He painted very ordinary things—bowler hats, green apples, clouds, and pipes—and then broke them by adding text or placing them in impossible contexts.

He once famously defended the painting by saying, "The famous pipe. How people reproached me for it! And yet, could you stuff my pipe? No, it's just a representation, is it not? So if I had written on my picture 'This is a pipe', I'd have been lying!"

Why Ceci n’est pas une pipe Still Breaks the Internet

Even now, nearly a century later, this image shows up on t-shirts, memes, and luxury advertisements. It’s the ultimate "meta" statement. In an era of deepfakes, CGI, and Instagram filters, Magritte’s warning about the treachery of images is actually more relevant than it was in the 1920s.

📖 Related: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

We live in a world of screens. When you look at a photo of a burger on your phone, you aren't looking at a burger. You’re looking at glowing pixels. When you see a "perfect" life on social media, you aren’t seeing a life; you’re seeing a curated, cropped, and filtered representation of one. Magritte was the original whistleblower on the fact that the map is not the territory.

Michel Foucault and the Philosophy of the Pipe

If you want to get really deep into the weeds, the French philosopher Michel Foucault wrote an entire book about this one painting. It's titled, naturally, This Is Not a Pipe.

Foucault argued that Magritte was breaking the ancient bond between "naming" and "seeing." Usually, when we see an object and a label, we assume they are the same thing. Magritte creates a "non-place" where the drawing and the words are actually in conflict.

- There is the thing itself (the actual physical pipe Magritte used as a model).

- There is the drawing of the pipe (the image).

- There is the text (the word "pipe").

Magritte separates all three. He shows us that language and art are just layers we peel over reality, and often, those layers don't actually touch the truth of the object. It’s kind of a mind-trip. It makes you realize that everything we communicate is a bit of a translation error.

The Humor Behind the Canvas

People often forget that Magritte was kind of a funny guy. He lived a very quiet, middle-class life in Brussels. He didn't have a giant studio; he often painted in the corner of his dining room. He wore a suit. He looked like a bank clerk.

This mundane lifestyle fed into his art. By taking the most boring, standard-issue objects and pointing out their inherent "falseness," he made the everyday feel strange. It’s a bit like a stand-up comedian pointing out something obvious that you’ve never noticed before. "What's the deal with pipes?" he might as well be saying.

But the humor has a sharp edge. It forces us to acknowledge that we are constantly being deceived by our own eyes.

👉 See also: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

How This Influenced Everything From Pop Art to Memes

Without Magritte, we might not have had Andy Warhol’s soup cans. Pop Art took the idea of "the image as an object" and ran with it. When Warhol painted Campbell’s soup, he was doing a variation of what Magritte did—taking a commercial, recognizable symbol and stripping away its utility until only the "image" remained.

In the digital age, Ceci n’est pas une pipe has become the grandfather of the meme. A meme is just an image with text that changes its meaning. Magritte did that first. He took a recognizable icon and used text to subvert it entirely.

Common Misconceptions About the Painting

A lot of people think the painting is just about "art being fake." That’s a bit too simple. It’s actually about the failure of language.

The word "pipe" is just a sound we’ve all agreed means a specific smoking tool. The letters P-I-P-E have no "pipeness" in them. If we all decided tomorrow that a pipe was called a "glorp," then the painting would have to say Ceci n’est pas une glorp. Magritte is poking fun at the fact that we rely on these arbitrary labels to understand our world.

Another mistake? People think he was the only one doing this. While he was the most famous, the Surrealists were all playing with the "image/word" divide. However, Magritte’s execution was the cleanest. It looks like a page from a primary school textbook, which makes the "lie" feel even more jarring.

What You Can Learn From a 100-Year-Old Pipe

So, what do you actually do with this information? Is it just fun trivia for a cocktail party? Maybe. But there’s a practical side to understanding the treachery of images.

We are bombarded with visual information. Advertisers use the "pipeness" of images to sell us things. They show us a refreshing-looking soda, and our brains react as if we are actually tasting it. Magritte’s work is a mental circuit breaker. It teaches us to pause and ask: "What am I actually looking at? Am I looking at reality, or a very convincing version of it?"

✨ Don't miss: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

This applies to everything:

- News headlines that use "loaded" language to frame a photo.

- AI-generated images that look indistinguishable from reality.

- The way we present ourselves online versus who we actually are.

Basically, Magritte was the first person to tell us "don't believe everything you see on the internet," decades before the internet existed.

Taking the Magritte Approach to Life

If you want to apply this "Surrealist Skepticism" to your own life, start by looking at objects not as what they do, but as what they are.

Next time you're looking at a photo on your phone, remind yourself: Ceci n'est pas un smartphone. It’s a reflection. It’s data. It’s light.

When you start to decouple the label from the object, the world gets a lot more interesting. You stop taking things for granted. You start to see the "treachery" everywhere—and in that treachery, there is a lot of room for creativity and new ways of thinking.

Actionable Steps for Modern Image Literacy

Don't just look—analyze. Here is how to apply the Magritte mindset today.

- Check the Frame: When looking at any "truth-telling" image, ask what was cropped out. Magritte chose to isolate the pipe to make his point. What is being isolated in the photos you see today?

- Question the Labels: Words change how we perceive images. Try looking at an image first without reading the caption. Does the meaning change once you read the text? That’s the "Treachery" in action.

- Study the Medium: Magritte used oil paint to mimic a commercial illustration. Today, we use filters to mimic film or "authenticity." Recognize the tool being used to manipulate your perception.

- Visit the Original: If you’re ever in Los Angeles, go to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Seeing the physical painting in person—the actual texture of the paint—is the final meta-joke. Because even then, it’s still not a pipe.

Magritte didn't want to confuse us for the sake of confusion. He wanted us to wake up. He wanted us to realize that the world we "see" is often just a collection of symbols and signs that we've stopped questioning. Once you start questioning the pipe, you start questioning everything else. And that’s exactly where art is supposed to take you.

Next Steps for the Curious

To truly grasp the impact of this work, look into the "Linguistic Turn" in 20th-century philosophy. This movement explored how language doesn't just describe our world, it actually constructs it. Magritte’s painting is the visual mascot for this entire field of study. You might also want to look up Magritte's other "word-paintings," like The Key of Dreams, where he pairs images with intentionally "wrong" labels—like a horse labeled "The Door." It’s a great way to further break your brain’s reliance on easy shortcuts.