You've probably seen the clickbait. A sleek, silver train blurring through a transparent tube while dolphins swim overhead. It’s a staple of "future tech" YouTube channels and speculative magazines that have been promising us a tunnel from New York to London for the better part of a century. It sounds like science fiction. Honestly, it mostly is. But the physics behind why we don't have a 3,500-mile hole under the Atlantic are actually more fascinating than the fantasy itself.

We can land rovers on Mars. We can split the atom. Yet, we still spend seven hours cramped in a pressurized metal tube at 35,000 feet just to get from JFK to Heathrow. Why? Because the Atlantic Ocean is a nightmare for engineers.

The 3,000-Mile Engineering Headache

To build a tunnel from New York to London, you aren't just digging a hole. You're fighting the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This is a massive underwater mountain range where tectonic plates are literally pulling apart. If you tried to lay a traditional tunnel on the seabed, the earth would eventually just snap it like a twig.

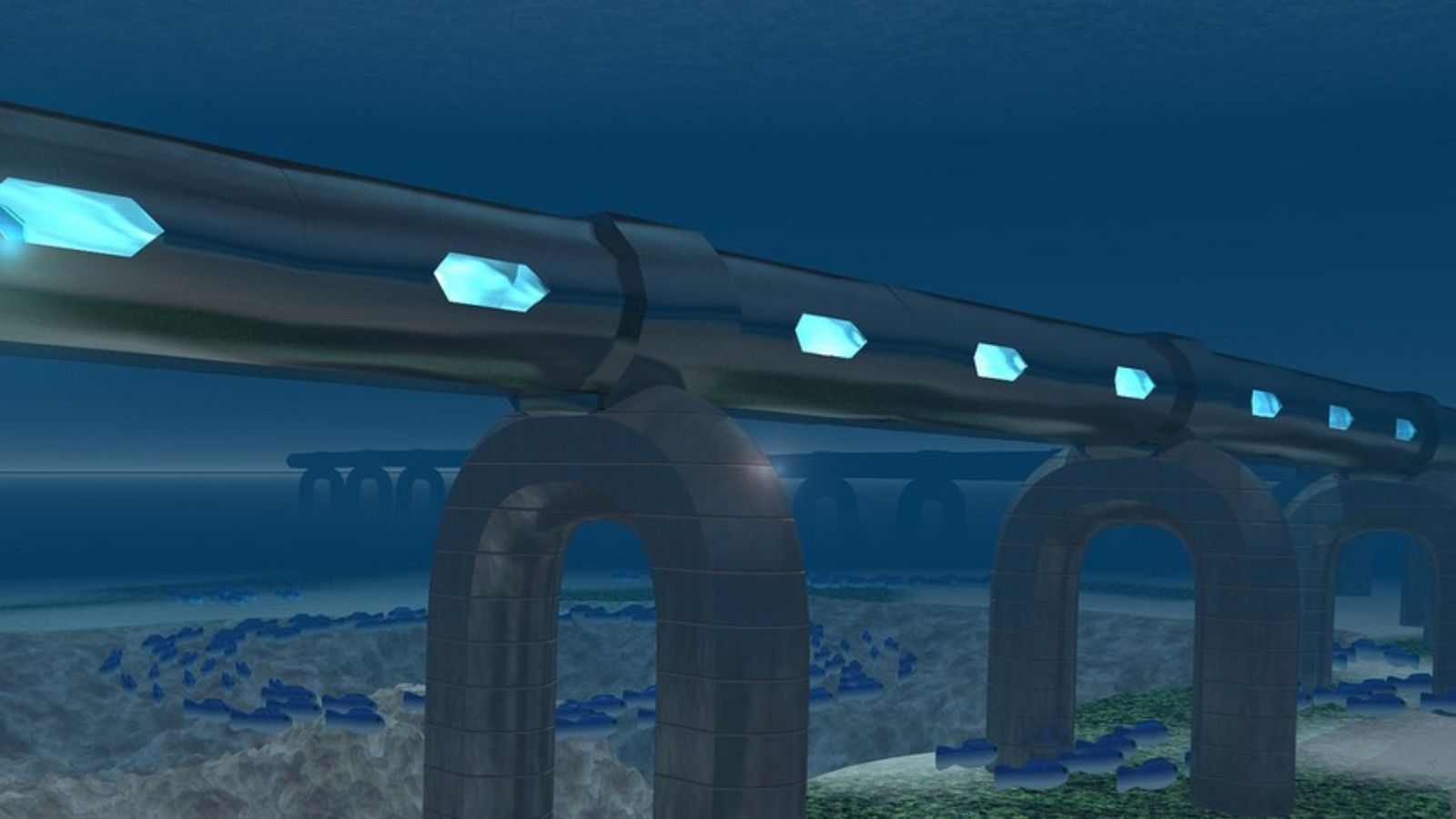

Robert Salter, a lead engineer at the RAND Corporation back in the 1970s, was one of the first to take this seriously. He didn't suggest a tunnel through the rock. He proposed something called the VHST (Very High Speed Transit) system. His idea? A vacuum-sealed tube floating about 150 feet below the surface of the ocean. It would be tethered to the floor with massive cables. By sucking all the air out of the tube—creating a vacuum—a maglev train could theoretically hit speeds of 5,000 mph.

Think about that. You could finish a cup of coffee in Manhattan and be in Central London before the caffeine even hits your bloodstream. Roughly 54 minutes.

But the scale is staggering. The English Channel Tunnel—the "Chunnel"—is only 31 miles long. It cost about £9 billion and took six years to build. A transatlantic version would be 100 times longer. It would require millions of tons of steel and concrete, and a logistics chain that doesn't currently exist on this planet.

Why We Can't Just "Hyperloop" It

Elon Musk brought the "vacuum tube" idea back into the mainstream with the Hyperloop, but the ocean adds a layer of "nope" that most people ignore.

👉 See also: Lateral Area Formula Cylinder: Why You’re Probably Overcomplicating It

The pressure at the bottom of the Atlantic is immense. At average depths of 12,000 feet, the water pressure is about 5,800 pounds per square inch. If a tiny crack formed in a tunnel from New York to London, the incoming water wouldn't just leak; it would cut through steel like a laser.

Then there's the air. Or the lack of it.

To maintain a vacuum over 3,000 miles is a feat of pumps and seals that we haven't mastered on a scale larger than a few kilometers at test tracks like those in Nevada. If the vacuum fails, the air resistance at supersonic speeds creates enough heat to melt the train. You’d basically be riding inside a giant friction cooker.

The Cost is Absolutely Ridiculous

Let’s talk money. Because that’s where these dreams usually go to die.

Estimates for a tunnel from New York to London start at around $12 trillion. To put that in perspective, the entire GDP of the United Kingdom is roughly $3 trillion. You would need the world's largest economies to pool their resources for decades to build a single transit line.

From a business standpoint, it’s a hard sell. Airlines are flexible. If demand for New York to London drops, they fly the planes to Tokyo or Dubai. A tunnel is fixed. If the economy shifts or a new technology emerges, you’re left with the world’s most expensive, water-filled pipe.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

What the Experts Say

Dr. Frank Davidson, who was a coordinator for the English Channel Tunnel project, once noted that the technology to build a transatlantic link technically exists. We know how to build floating bridges. We know how to build maglevs. We know how to tunnel.

The missing piece isn't the "how," it's the "why."

SpaceX’s Starship is currently being developed with "Earth-to-Earth" travel in mind. The goal is to use suborbital rockets to transport people from NYC to London in about 30 minutes. It’s loud, it’s violent, and it’s basically sitting on a controlled explosion, but compared to building a 3,000-mile underwater vacuum, it’s remarkably cheap.

When you compare the two, the tunnel starts to look like a Victorian solution to a 21st-century problem. We are a species that likes to go over things, not under them, especially when "under" involves the crushing weight of the Atlantic.

The Real Risks Nobody Talks About

Security is the elephant in the room. A tunnel is a singular, vulnerable point of failure.

A single intentional disruption at the midpoint of the Atlantic would be a global catastrophe. Rescue operations at those depths and distances from shore are virtually impossible. In a plane, you have life vests and a chance at a water landing. In a vacuum tube under the sea? There is no Plan B.

🔗 Read more: robinhood swe intern interview process: What Most People Get Wrong

Also, consider the ecological impact. Dragging tethers and tubes across the ocean floor would disrupt deep-sea ecosystems we barely understand. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is home to hydrothermal vents and life forms that exist nowhere else. Turning their home into a construction site is a hard "no" from every environmental agency on earth.

Moving Forward: Real World Steps

Since a tunnel from New York to London isn't happening in our lifetime, where should you actually put your focus if you're interested in the future of travel?

Keep an eye on Boom Supersonic. They are currently working on the "Overture," a supersonic jet designed to run on 100% sustainable aviation fuel. It aims to cut the New York to London flight time down to about 3 hours and 30 minutes. It's not a 54-minute train ride, but it’s a project that has actual funding, real prototypes, and a clear path to FAA certification.

If you are fascinated by the engineering of the deep, look into the fixed link projects currently happening in Europe and Asia. The Fehmarnbelt Tunnel between Denmark and Germany is a great example of an "immersed tunnel" that pushes the boundaries of what we can do under the waves.

The dream of the transatlantic tunnel is a beautiful monument to human ambition. It reminds us that we are always looking for a way to make the world smaller. But for now, the Atlantic remains too wide, too deep, and far too expensive to conquer with a shovel.

Actionable Insights for the Future-Minded:

- Follow Aerospace, Not Civil Engineering: If you want faster transatlantic travel, watch the development of the SABRE engine by Reaction Engines. This "synergetic air-breathing rocket engine" is more likely to bridge the gap than any tunnel.

- Study High-Speed Rail (HSR) Constraints: Understand that the primary barriers to projects like this are often political and environmental rather than just mechanical.

- Monitor Suborbital Testing: Watch the progress of Starship's reentry heat shields. If they can master rapid, reusable suborbital hops, the "tunnel" concept will likely be relegated to history books forever.

The Atlantic isn't just an ocean; it's a physical barrier that demands respect. We might bridge it one day, but it won't be with a train. It will be with something that flies.