It was a Monday. August 21, 2017. Millions of people across the United States stopped what they were doing and looked up—hopefully with those goofy cardboard glasses on. For the first time in nearly a century, a total solar eclipse sliced across the entire country, from the Pacific to the Atlantic. People called it the "Great American Eclipse," and honestly, the hype was actually justified. This wasn’t just some grainy science textbook diagram coming to life; it was a massive, cross-country event that turned day into night for a few eerie minutes.

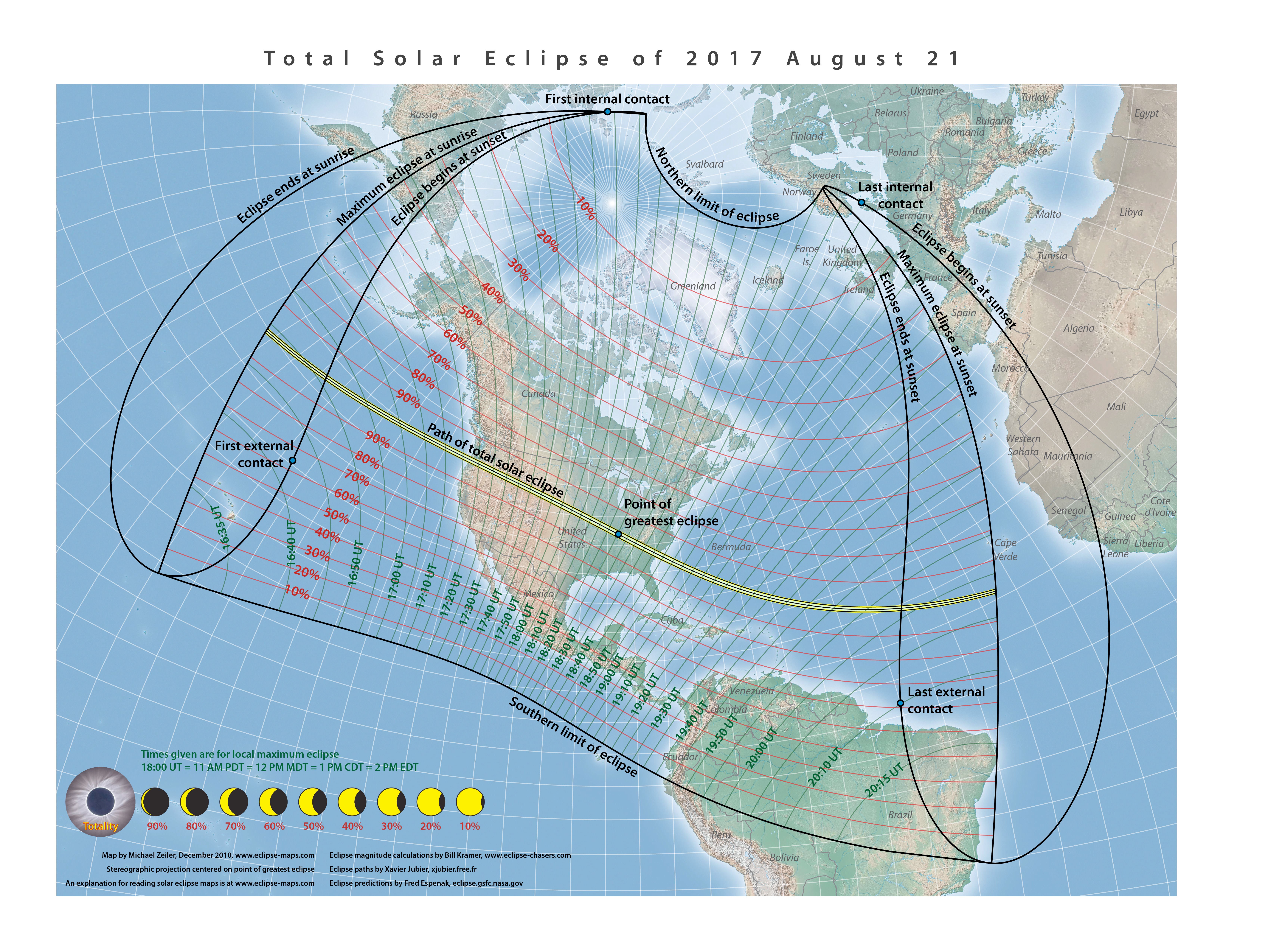

The total eclipse 2017 path was a narrow ribbon of shadow, about 70 miles wide, that touched 14 states. If you were outside that path, you saw a partial eclipse. Cool, sure, but it wasn't the "big one." Inside the path of totality? That’s where the magic happened. The temperature dropped. Crickets started chirping because they thought it was dusk. The sun’s corona—that ghostly, wispy outer atmosphere—became visible to the naked eye. It was visceral.

👉 See also: Davison Michigan Weather Radar: Why Your App Might Be Lying to You

Mapping the Shadow: Where the Total Eclipse 2017 Path Actually Went

The shadow first hit land at Government Point, Oregon, at 10:15 a.m. local time. From there, it raced southeast. It didn't linger. The moon’s shadow moves at supersonic speeds, so if you were standing in one spot, you only had a couple of minutes of total darkness at most.

It’s wild to think about the geography. The path cut through Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. A tiny sliver of Montana and Iowa also got in on the action. Cities like Salem, Nashville, and Charleston were basically ground zero for eclipse tourism.

Small towns that usually have a population of a few hundred suddenly found themselves hosting tens of thousands of people. Take Madras, Oregon, for example. It’s a quiet spot, but because it had some of the best weather prospects for a clear sky, it became a temporary metropolis. Traffic jams lasted for nine hours on two-lane highways. People were camping in fields, parked on shoulders, just waiting for those two minutes of darkness.

The Sweet Spot in Southern Illinois

If you wanted the absolute maximum duration of totality, you had to head to a spot just south of Carbondale, Illinois. Specifically, a place near Giant City State Park. There, the sun was blocked for 2 minutes and 41.6 seconds.

NASA and various universities set up huge observation camps there. It’s actually a bit of a celestial coincidence, but Carbondale was also in the path of the 2024 eclipse. Talk about luck. Most places have to wait hundreds of years between total eclipses, but this little corner of Illinois got two in less than a decade.

What People Got Wrong About the Path

A lot of people thought that being "close" to the path was good enough. It wasn't.

There’s a massive difference between a 99% partial eclipse and 100% totality. At 99%, the sky gets a bit dim, like a cloudy day, but the sun is still incredibly bright. You still need glasses. You don't see the corona. You don't see the stars. You miss the "diamond ring" effect. Honestly, the total eclipse 2017 path was an all-or-nothing deal. If you were even five miles outside that line, you missed the main event.

I remember talking to people who stayed in Portland or St. Louis thinking they'd see it all. They didn't. They saw a weird shadow, but they didn't get the life-changing experience of the sun disappearing.

👉 See also: New Jersey Weather Yesterday: Why the Arctic Shift Caught Us Off Guard

The Logistics Nightmare

Traffic was the real story for anyone who didn't stay put. The Federal Highway Administration actually called it one of the largest planned "special events" in history. But was it really planned?

In Wyoming, the population essentially doubled for a weekend. The I-25 corridor became a parking lot. It turns out that our infrastructure isn't really built for several million people to decide to drive to the same 70-mile-wide strip of land all at once. If you were trying to chase the shadow by car, you probably ended up staring at a bumper instead of the sky.

Science Under the Shadow

It wasn't just for tourists. This was a massive win for the scientific community.

Researchers used the total eclipse 2017 path to study the sun's corona in ways that satellites just can't. When the moon blocks the main disk of the sun, we can see the lower corona, which is usually washed out by the sun's glare.

- Citizen Science: The "Eclipse Mega-movie" project stitched together thousands of photos from regular people along the path to create a continuous view of the eclipse as it crossed the country.

- Animal Behavior: Zoos along the path, like the Riverbanks Zoo in South Carolina, recorded animals doing weird things. Giraffes started galloping. Galápagos tortoises started mating. Birds just went silent.

- Atmospheric Pressure: The sudden cooling caused "eclipse waves" in the atmosphere, similar to the wake of a boat.

Dr. Thomas Zurbuchen, who was the associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate at the time, pointed out that this was a unique opportunity to see the Earth-Sun-Moon system as one cohesive unit. We weren't just looking at the sun; we were feeling the Earth react to its absence.

The Weather Gamble

You can calculate the path of an eclipse down to the millisecond years in advance, but you can't predict the clouds.

On the morning of August 21, the Southeast was a nervous wreck. South Carolina is notorious for afternoon thunderstorms in August. Meanwhile, the high deserts of Oregon and Idaho were almost guaranteed to be clear.

In the end, most of the country got lucky. There were some clouds in Missouri and parts of the coast, but for the most part, the total eclipse 2017 path lived up to the hype. It was a rare moment of collective focus. In an era where everyone is looking at different screens, everyone was looking at the same sky.

Why the 2017 Path Matters Now

Looking back, 2017 was a trial run for the 2024 eclipse. It taught us how to handle the crowds and how to educate the public about eye safety. Remember the "fake" eclipse glasses scandal? Amazon had to recall thousands of pairs that weren't actually ISO-certified. That 2017 experience made us a lot smarter for future events.

It also sparked a new generation of "umbraphiles"—eclipse chasers. People who saw totality for the first time in 2017 realized that pictures don't do it justice. The way the light turns silver, the way the wind picks up, the 360-degree sunset on the horizon... you can't capture that on an iPhone.

Actionable Steps for Future Eclipses

If you missed the 2017 path and the 2024 path, you're going to have to wait or travel. Total solar eclipses happen roughly every 18 months somewhere on Earth, but they usually happen over the ocean or remote areas.

- Check the Saros Cycle: Eclipses come in families. If you want to see the "sequel" to the 2017 eclipse, look for its Saros series siblings.

- Verify Your Gear: Never use glasses from 2017 for a future eclipse. The filters can degrade, and your eyesight isn't worth the risk. Buy new, ISO 12312-2 certified viewers from a reputable vendor like American Paper Optics or Rainbow Symphony.

- Book Two Years Out: If an eclipse path is hitting a popular destination (like Spain in 2026), hotels will be gone before you even think to look.

- Get to the Centerline: Don't settle for the edge of the path. The duration of totality drops off significantly as you move toward the boundaries. Stay as close to the center of the path as possible.

- Stop Taking Photos: This is the best advice anyone can give. If you only have two minutes of totality, don't spend it fiddling with your camera settings. Look at it. Feel it. The professional photographers will have better pictures anyway.

The 2017 path was a reminder that we live on a rock spinning through space. It's easy to forget that until the sun disappears in the middle of a Tuesday.