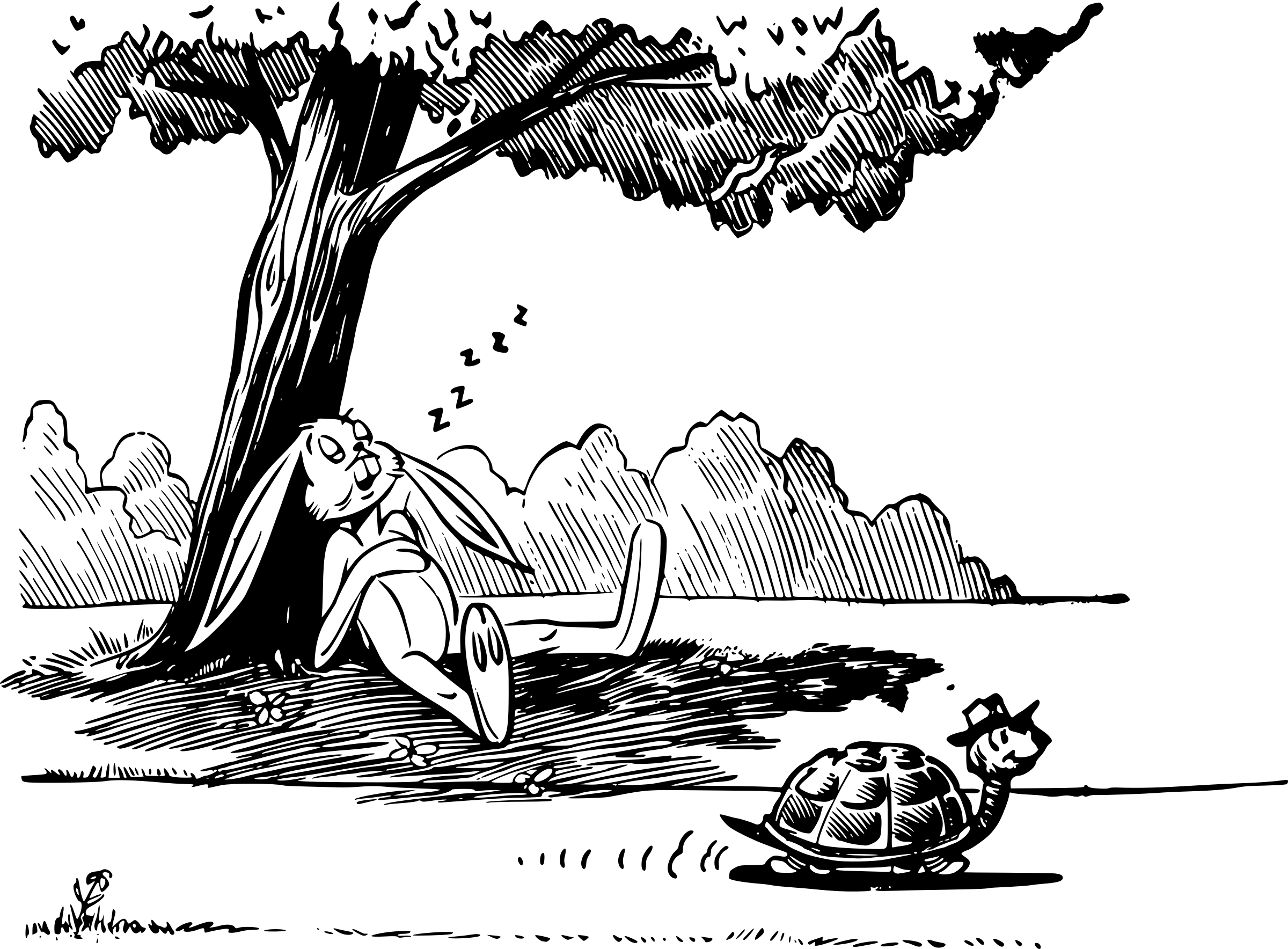

You know the drill. A rabbit—technically a hare—gets cocky, takes a nap, and loses a race to a turtle who barely moves faster than a glacier. It's the ultimate underdog story. Honestly, though, if you look at the The Tortoise and the Hare through a modern lens, it's kind of a weirdly aggressive fable. We’ve been told since kindergarten that "slow and steady wins the race," but let’s be real: in a world of fiber-optic internet and overnight shipping, nobody actually wants to be the tortoise. We want the hare’s speed without the hare’s ego.

It’s one of Aesop’s Fables. People argue about when exactly these stories were written, but we’re looking at roughly 620 to 564 BCE. That is a massive amount of time for a story about a reptile and a lagomorph to stay relevant. Why does it stick? Probably because we all know a "hare"—that person who is naturally gifted but lazy as hell. And we’ve all felt like the tortoise, just grinding away while nobody notices.

What Actually Happened in the Original Fable?

Most people remember the cartoon versions. You might picture the hare in a track suit or the tortoise with a cane. But the Greek original is pretty sparse. There’s no complex dialogue. There are no cheering crowds of forest animals in the earliest versions. It’s basically a short, sharp shock to the system meant to illustrate Aponia—the Greek concept of laziness or lack of effort.

The hare wasn't just fast; he was mocking. That’s the detail people miss. It wasn't just a race; it was a character assassination. The tortoise didn't win because he was "better." He won because the hare literally forgot he was in a competition.

✨ Don't miss: Holiday Party Snacks: What Most People Get Wrong About Feeding a Crowd

Think about that.

The hare’s failure wasn't a lack of ability. It was a total collapse of focus. In some variations of the story, particularly those collected by Babrius or Phaedrus later on, the stakes change slightly, but the core remains: arrogance is a massive blind spot. If you’re looking for a historical deep dive, you’ll find that "The Tortoise and the Hare" wasn't even the only "slow vs fast" story Aesop told. He had a whole thing for animal metaphors. But this one became the gold standard for meritocracy.

The Problem with "Slow and Steady"

Here is the thing. "Slow and steady" is actually terrible advice in a lot of situations. If you’re running out of a burning building, you don't want to be slow and steady. If you're a startup trying to beat a giant corporation to market, "slow" usually means you go bankrupt.

We’ve turned The Tortoise and the Hare into a mantra for consistency, which is good. But we’ve also used it to excuse a lack of urgency.

Modern psychology has a different take on this. Look at the work of researchers like Anders Ericsson, who studied "deliberate practice." The tortoise wasn't just moving slow; he was moving persistently. There’s a huge difference. If the tortoise had stopped to eat a leaf, he’d have lost. The win came from the lack of pauses, not the speed of the gait.

Sometimes the hare is actually right. If the hare hadn't napped, he would have won by a mile. He would have been home, showered, and having dinner before the tortoise hit the halfway mark. The lesson isn't "don't be fast." The lesson is "don't stop until you're actually done." We focus so much on the turtle's pace that we forget the hare's mistake was psychological, not physical.

Why Brains Love This Story

There’s a reason this specific fable is indexed so highly in our collective consciousness. It hits on "Loss Aversion" and "Overconfidence Bias."

- Overconfidence Bias: The hare assumes his past performance guarantees future results.

- The Underdog Effect: Humans are hardwired to root for the entity with the lower probability of winning. It releases more dopamine when the "wrong" person wins.

When you read The Tortoise and the Hare to a kid, you’re teaching them about the reliability of character over the flashiness of talent. It’s a comforting thought. We want to believe that hard work beats talent when talent doesn't work hard. It makes the world feel fair. But as we know from real life, the world isn't always fair. Sometimes the hare doesn't nap. Sometimes the hare is both fast and disciplined. That’s the person who really wins, but they don't make for a very comforting bedtime story.

The Biological Reality (Just for Fun)

Hares can hit speeds of 45 miles per hour. A desert tortoise? Maybe 0.2 miles per hour. To put that in perspective, if the race was just one mile long, the hare would finish in about 80 seconds. The tortoise would take five hours. For the hare to lose, he doesn't just need a "quick nap." He needs a full-blown hibernation.

👉 See also: The Real Reason Everyone Still Ends Up at Brownstone Bar & Restaurant Brooklyn NY 11201

He basically has to forget the race exists for 4 hours and 58 minutes.

This highlights how extreme the metaphor is. The fable isn't about a close race. It's about a total, catastrophic failure of will.

Business Lessons from a 2,500-Year-Old Turtle

If you’re in a leadership role, you see this dynamic constantly. You have the "Rockstars" (Hares) and the "Grinders" (Tortoises).

Managers often make the mistake of over-relying on the Hares. They’re the ones who pull off the "miracles" at the last minute. They stay up all night to finish a presentation that they ignored for two weeks. It looks impressive. It’s flashy. But it’s also high-risk. If that Hare gets a cold, or gets bored, or decides they don't care anymore, the project dies.

The Tortoises are the ones who have the draft done three days early. They aren't "innovative" in the flashy sense, but they are reliable.

A healthy organization needs both, but the fable warns us that reliability is the actual foundation of success. Look at companies like Toyota. Their whole philosophy of Kaizen (continuous improvement) is basically The Tortoise and the Hare applied to car manufacturing. Small, incremental gains that eventually lead to total market dominance. It’s not sexy. It doesn't make for a high-octane movie trailer. But it works.

Cultural Variations of the Race

Interestingly, Aesop isn't the only one who thought of this. There are versions of this story in African folklore involving a turtle and a different fast animal, sometimes a deer or a bird. In some of these versions, the turtle actually cheats!

👉 See also: Kool-Aid Pickles Explained: Why This Weird Southern Snack Actually Works

In one West African version, the turtle lines up his family members along the race track. Every time the faster animal asks, "Are you there yet?" a different turtle (who looks exactly like the first one) sticks his head out of the grass and says, "Yep, I'm ahead of you!"

That’s a completely different lesson. That’s not about persistence; it’s about "working smarter, not harder." It’s about using your resources and outthinking a superior physical opponent. It’s cynical, sure, but it’s also arguably more realistic than the idea that you can outrun a rabbit by walking slowly.

The Modern Rebuttal: The "Fast and Steady" Model

In the 21st century, the dichotomy of The Tortoise and the Hare is starting to break down. We have a third option now: The Robot.

Automation is fast and steady. It doesn't nap like the hare, and it doesn't tire like the tortoise. This changes the moral of the story for the modern worker. If your only value is "being steady," a machine can do that better than you. If your only value is "being fast," a machine can do that better too.

The real "win" now comes from direction. The tortoise knew where the finish line was. The hare knew where it was too, but he didn't respect it. In an age of infinite distractions—TikTok, emails, the 24-hour news cycle—we are all hares surrounded by a thousand beds. The "finish line" is harder to see than ever.

How to Apply the Lesson Without Being a Boring Turtle

You don't have to be slow to win. You just have to be consistent. If you want to actually use the logic of the fable in your life, stop focusing on the "slow" part. Focus on the "steady" part.

- Define your "Nap" triggers. What makes you check out of the race? Is it social media? Is it burnout? Is it a "win" that makes you feel like you can slack off? Identify the things that make you feel like the hare mid-race.

- Audit your pace. If you are moving so slowly that you’ll never reach the goal in your lifetime, you aren't being the tortoise; you’re just stalling. You need enough speed to make the goal relevant.

- Respect the competition. The hare’s biggest sin was thinking the tortoise didn't matter. Never assume your lead is unshakeable.

- Value the "boring" work. The tortoise’s journey was incredibly boring. Step after step. No sprints. No highlights. Most of success is just doing the boring stuff when you'd rather be doing literally anything else.

The story of The Tortoise and the Hare isn't really about a race at all. It's about the internal struggle between our ego and our discipline. The hare is our desire for instant gratification and the belief that we are "special" enough to skip the work. The tortoise is the part of us that accepts reality—the reality that distance requires time and effort, no matter how talented we are.

Next time you feel like you're "way ahead" and can afford to slack off, just remember the hare. He had a 4-hour and 58-minute lead and he still managed to blow it. Don't be that guy. Finish the race, then take your nap. It tastes better that way anyway.

Actionable Steps for Growth:

- Pick one project you've been "napping" on because you think you're "good enough" to finish it later.

- Set a timer for 20 minutes of "Tortoise Time"—pure, slow, undistracted progress.

- Delete one distraction from your phone that acts as your "grassy knoll" where you lose focus.

- Track your consistency for seven days; don't worry about the "speed" of your results, just the fact that you showed up every single day.

Consistency trumps intensity every single time.

The end.