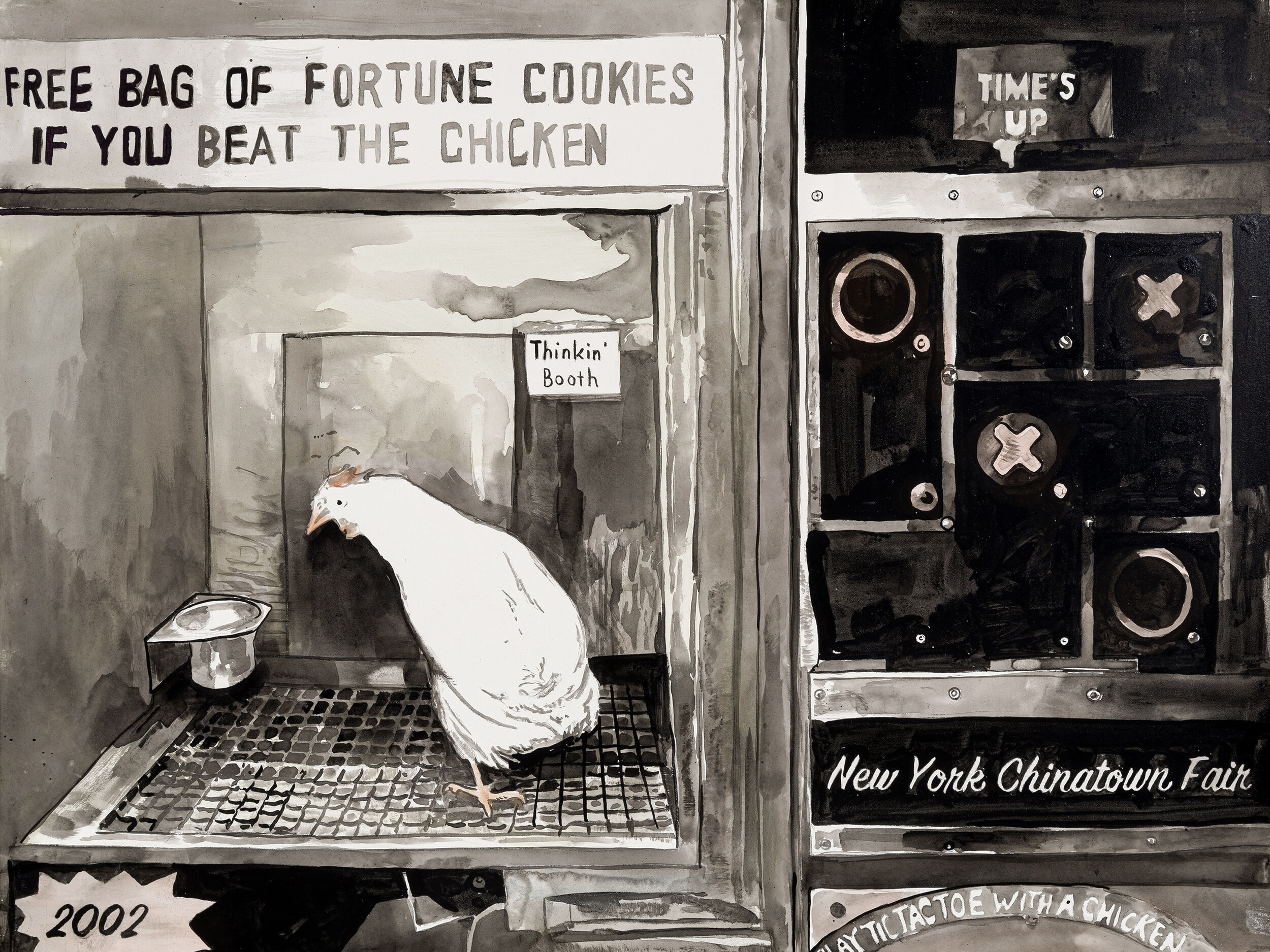

You’re standing in a dimly lit arcade or a dusty county fair booth, staring through a plexiglass window at a live hen. Her name is probably Ginger or Henrietta. She looks focused. Maybe a little bored. You drop a couple of dollars into the slot, the lights flash, and suddenly you’re locked in a high-stakes match of strategy against a creature that spends the rest of its day pecking at cracked corn. You lose. Then you lose again. Most people walk away from the tic tac toe chicken feeling a weird mix of humiliation and genuine awe. How does a bird with a brain the size of a bean outmaneuver a human adult at a game we’ve played since kindergarten?

It’s not magic. It’s also not "super-intelligence" in the way we usually think about it.

The phenomenon of the tic tac toe chicken is a fascinating intersection of behaviorist psychology, clever engineering, and a brutal mathematical reality that favors the bird every single time. If you’ve ever wondered if the game is rigged—well, it’s not rigged in the way you think, but you were never going to win anyway. Let's get into the weeds of how this actually works.

The Ghost in the Coop: How B.F. Skinner Started This

To understand why that chicken just took your five bucks, we have to go back to the mid-20th century. Specifically, we have to look at the work of B.F. Skinner, the father of operant conditioning. Skinner wasn't interested in making chickens famous; he wanted to understand how reinforcement shapes behavior. His students, Keller and Marian Breland, eventually took these academic concepts and turned them into a business called Animal Behavior Enterprises (ABE).

They were the true pioneers. They realized that you could train animals to do almost anything if you broke the task down into tiny, repeatable steps and offered the right reward.

They didn't just train chickens. They trained crows to pick up trash, dolphins to find mines, and even tried to train pigeons to guide missiles during World War II. The tic tac toe chicken was one of their most successful commercial ventures, popping up in places like Atlantic City’s Steel Pier and various roadside attractions across the United States. It was the perfect gimmick. It looked like the chicken was thinking. In reality, the chicken was just participating in a very specialized "if-then" loop.

The "Logic" of a Chicken Brain

When you make a move, you're using your prefrontal cortex to visualize future outcomes. You're thinking, "If I go in the corner, I can set up a fork." The chicken? Not so much. The bird is looking for a light.

Inside the console, there’s a computer—or in the old days, a series of mechanical relays—that calculates the optimal move in response to yours. Tic-tac-toe is what mathematicians call a "solved game." This means that if both players play perfectly, the game will always end in a draw. However, since the computer is doing the "thinking," it never makes a mistake. Once the computer decides where the "X" or "O" should go, a small light or a specific visual cue triggers inside the chicken’s coop.

The chicken has been trained through thousands of repetitions. Light goes on? Peck the light. Pecking the light releases a single grain of food. To the bird, it isn’t playing a game. It’s foraging in a very high-tech environment.

Why You Keep Losing (It's Not Just the Bird)

You’ve played this game since you were six. You know the rules. So why do so many people lose to the tic tac toe chicken?

- The Pressure Cooker: There’s a crowd watching. You’re laughing, maybe you’ve had a beer, and you’re self-conscious about losing to a farm animal. You make a "lazy" move. In tic-tac-toe, one lazy move is all it takes for a perfect opponent to crush you.

- The First-Move Advantage: In many arcade setups, the chicken (the computer) is programmed to go first. If the first player knows what they are doing, the best the second player can hope for is a tie.

- The Draw is a Loss: In most of these booths, a draw counts as a win for the house. You don't get your money back for a "Cat’s Game." Since the computer is programmed for perfect play, the only way you "win" is if the computer lets you—which it won't.

Honestly, it’s a brilliant business model. The overhead is just chicken feed and a bit of electricity.

The Controversy: Is it Cruelty or Just Work?

Not everyone finds the tic tac toe chicken charming. Over the years, animal rights activists have targeted these booths, arguing that keeping a bird in a small, dark box for hours on end is inhumane. One of the most famous cases involved a chicken at a fair in New York where protesters claimed the bird was stressed by the loud arcade noises and the flashing lights.

Advocates for the trainers, however, argue that these chickens are actually quite well-off. They aren’t being processed for meat, they are kept in climate-controlled environments, and they get to engage in "species-typical behavior"—which is pecking for food.

Whether you find it exploitative or just a quirky relic of Americana, the ethics of animal entertainment have shifted significantly since the Brelands first started their work. You don't see these booths as often as you used to. They've mostly been replaced by digital versions, though some "old school" spots like Casino Pier in Seaside Heights have kept the tradition alive for decades.

Real Expert Insight: The Math of the Game

If you want to get technical, tic-tac-toe has 362,880 possible sequences of play. That sounds like a lot, but for a simple computer, it's nothing. Even a basic microcontroller from the 1970s could hold the entire "decision tree" for the game.

When the tic tac toe chicken "plays," the computer follows a specific hierarchy:

- Win: If the bird has two in a row, play the third.

- Block: If the human has two in a row, block them.

- Fork: Create an opportunity where there are two ways to win.

- Center: Take the middle square if it's open.

Because the computer executes this flawlessly, the chicken looks like a genius. It’s a perfect example of how humans anthropomorphize animals. We see a bird "choosing" a move, when really, we’re just watching a feathered biological interface for an unbeatable algorithm.

How to Not Lose to a Chicken

If you happen to find one of these machines in the wild, you probably want to save face. You might not be able to "win" in the traditional sense, but you can definitely force a draw.

First, never let the chicken take the center if you can help it. If you go first, take a corner. This is statistically your best opening. If the chicken goes first and takes a corner, you must take the center. If you don't, you've already lost; you just don't know it yet.

Most people fail because they try to "trap" the bird. Don't try to trap the bird. The bird is a computer. Just play for the draw. A draw is the only way to leave with your dignity intact, even if you don't get the "I beat the chicken" t-shirt.

The Legacy of the Arcade Hen

The tic tac toe chicken is more than just a weird carnival trick. It’s a piece of psychological history. It represents the moment when we realized that animals could be "programmed" just as effectively as machines. It’s also a reminder of our own human fallibility. We are prone to distraction, ego, and simple mistakes—things a hen and a circuit board don't have to worry about.

The next time you see that plexiglass box, look at the bird. She isn't thinking about your strategy. She isn't mocking your poor move. She's just waiting for that light to blink so she can get her next piece of corn.

✨ Don't miss: What is Strong Against Psychic Types: What Most People Get Wrong

Next Steps for the Curious:

- Research the Breland legacy: Look up "Animal Behavior Enterprises" to see the incredible (and sometimes weird) things they taught animals to do.

- Practice "Perfect Play": Spend ten minutes learning the tic-tac-toe optimal strategy map. It’s surprisingly small and will ensure you never lose to a human (or a bird) again.

- Find a local vintage arcade: Check sites like Roadside America to see if there are any remaining live chicken games near you—they are becoming increasingly rare.