He didn't have a name. At least, not one the Bible bothers to record. We just know him as the thief on the cross, a man dangling at the edge of history, gasping for air while the world literally went dark. Most people think they know the story: bad guy makes a last-second deal with God and gets into heaven. It’s the ultimate "get out of jail free" card, right?

Honestly, it’s a lot more complicated than a simple deathbed confession.

When you look at the accounts in Matthew, Mark, and Luke, you see a messy, violent, and deeply human moment that challenges basically everything we think about merit and religion. It’s not just a Sunday school story about being sorry. It’s a legal and theological explosion that still bothers people who like things to be "fair."

The Brutal Reality of First-Century Justice

Crucifixion wasn't for petty shoplifters. Let's be real. If you were being nailed to a piece of timber by the Romans, you weren't just a "thief" in the sense of someone who swiped a loaf of bread. The Greek word used is lestai. In that specific historical context, it usually referred to insurrectionists or violent bandits. These were men who lived outside the law, likely part of rebel groups trying to destabilize the Roman occupation.

They were "freedom fighters" to some, but brutal criminals to the state.

The thief on the cross was likely a peer of Barabbas. You’ve probably heard of him—the guy the crowd chose to release instead of Jesus. Imagine the psychological state of this man. He’s spent his life fighting, stealing, and hiding. Now, his lungs are collapsing under his own weight, and he’s hanging next to a man who is being mocked as a "King."

It’s a grisly scene.

Early on, both criminals actually joined in the mocking. Matthew 27:44 says "the rebels who were crucified with him also heaped insults on him." It wasn't an immediate conversion. It was a slow, agonizing realization. Something shifted in the atmosphere. Maybe it was the way Jesus didn't scream back. Maybe it was the "Father, forgive them" part. Whatever it was, one of them snapped out of the hatred.

The Dialogue That Changed Everything

The conversation recorded in Luke 23 is where the heavy lifting happens. One criminal is basically saying, "If you're so great, save yourself and us!" He wanted a physical rescue. He wanted his old life back.

👉 See also: Finding the University of Arizona Address: It Is Not as Simple as You Think

But the other guy—the one we call the "penitent thief"—shuts him down.

"Don’t you fear God?" he asks. He acknowledges his own guilt. He admits they are getting what their deeds deserve. That’s a massive moment. It’s rare for a person in their final moments of agony to stop blaming the system and own their mess. Then he turns his head—which would have been excruciatingly painful to do—and says, "Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom."

No "Our Father." No baptism. No long list of good deeds to balance the scales.

Jesus' response is the part that still makes traditionalists twitch. He doesn't tell the man he needs to do penance. He doesn't ask him to recite a creed. He just says, "Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise."

Why This Upsets the Religious Apple Cart

Religion is usually built on a "do this, get that" structure. If you work hard, you get the promotion. If you follow the rules, you get the reward. The thief on the cross destroys that logic entirely. He had zero time left to do anything good. He couldn't go back and return what he stole. He couldn't help the poor. He couldn't even get down to be baptized.

He was stuck.

This is what theologians call "Sola Fide" or faith alone, and it’s been a point of massive debate for centuries. Saint Augustine and later Martin Luther looked at this specific interaction as the ultimate proof that grace isn't something you earn. It’s something you accept when you have nothing left to offer.

Some people find this incredibly comforting. Others find it offensive.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe With Boiled Eggs That Actually Makes Breakfast Interesting Again

Think about it. If a person who has lived a life of violence and theft can be welcomed into "paradise" simply by asking, what does that say about the "good" people who spent their lives trying to be perfect? It suggests that the entry requirement isn't morality—it's humility. It’s a hard pill to swallow if you’ve spent forty years volunteering at a soup kitchen and think that's what earns you a spot in the afterlife.

The "Paradise" Problem

Let's get nerdy for a second. The word "paradise" (paradeisos) is actually an old Persian word for a walled garden. It’s where the King would walk with his friends. When Jesus uses this word, he’s not just talking about a cloud in the sky. He’s talking about intimacy and restoration.

There’s also a huge debate about the word "today."

Greek grammar is famously tricky with comma placement. Did Jesus mean "I’m telling you today, you will be with me..." or "Today you will be with me..."? Most scholars, including N.T. Wright, argue that Jesus was promising immediate companionship in the intermediate state after death. It’s a radical thought because it bypasses the idea of a long, drawn-out waiting room for the "not-quite-good-enough."

Historical Misconceptions and Later Legends

Because the Bible is so sparse on the details, humans did what humans do: they made stuff up. In later apocryphal writings, like the Gospel of Nicodemus, the thieves are given names: Dismas and Gestas.

Dismas (the "good" one) became a folk hero in some circles. There are legends that the two thieves actually met the Holy Family years earlier when they were fleeing to Egypt. The story goes that Dismas protected Mary and the baby Jesus from other bandits, and that's why he was "saved" later on.

It’s a nice story. It’s also almost certainly fake.

The Bible keeps him anonymous for a reason. By keeping him nameless and meritless, he becomes a placeholder for anyone. If he had a backstory of being a "secretly good guy," the whole point of grace would be watered down. He has to be a genuine "thief" for the story to work.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

The Psychological Impact of the Final Choice

Working in hospice or end-of-life care, people often talk about "the clarity of the end." The thief on the cross represents that moment where the ego finally dies before the body does.

One thief stayed bitter. He stayed trapped in his anger at the world, at Rome, and at the man hanging next to him. The other let go.

It's a study in human agency. Even when your hands and feet are nailed down, you still have the freedom to choose your perspective. You still have the freedom to acknowledge truth.

Actionable Insights from a 2,000-Year-Old Execution

So, what do you actually do with this? Whether you're religious or just interested in the historical and psychological weight of the narrative, there are a few takeaways that aren't just fluff.

1. It’s never actually too late to pivot.

The thief's story is the ultimate argument against the "I've messed up too much" mindset. If a violent insurrectionist can find peace in his final sixty minutes, your mistakes from last year or even this morning aren't the end of your story.

2. Focus on "Remember Me" over "Fix Me."

The thief didn't ask Jesus to take away the pain or even to save his life. He asked to be remembered. In our lives, we often obsess over fixing every circumstance. Sometimes, the real shift happens when we look for connection and meaning within the pain rather than just looking for an exit.

3. Stop the "Scales" Mentality.

If you spend your life weighing your good deeds against your bad ones, you'll always be anxious. The story of the thief on the cross suggests that the "scales" aren't how the universe actually works. Grace, by definition, is unfair. Acceptance is better than perfection.

4. Watch how people treat those who can do nothing for them.

The most telling part of the story is Jesus' attention. He was in the middle of his own trauma, yet he took the time to comfort a criminal who had zero to offer him in return. That’s a benchmark for leadership and character. How do you treat the "thieves" in your life—the people who can't help you, can't pay you back, and have nothing to offer?

The thief on the cross remains one of the most provocative figures in Western literature and theology because he is the ultimate "outlier." He didn't follow the program. He didn't finish the course. He just showed up at the very end and was told that was enough. It’s a scandalous idea, and honestly, that’s probably why we’re still talking about it two millennia later.

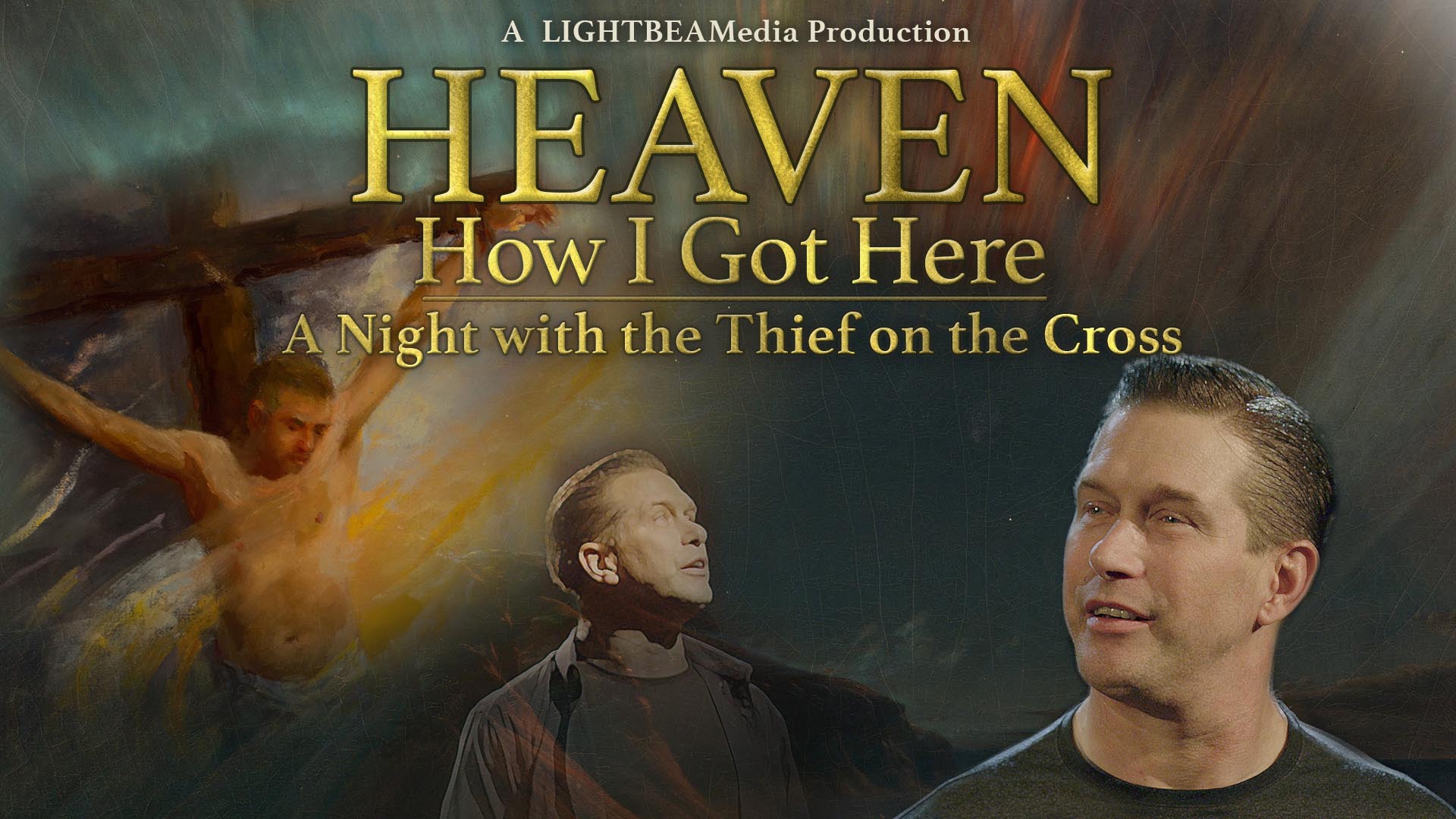

To explore this further, you can look into the historical context of Roman crucifixion in the works of Josephus or read the theological breakdown of the "intermediate state" in N.T. Wright’s The Resurrection of the Son of God. If you want to see how this story influenced art, look at Titian’s or Rubens’ depictions of the scene—they often capture the raw, gritty contrast between the two men better than any text can.