Texas history is usually taught as a series of heroic last stands and rugged frontiersmen in coonskin caps. You’ve probably heard of the Alamo. You know about Davy Crockett. But the Texas Revolution was a lot messier—and frankly, more fascinating—than the "good guys vs. bad guys" narrative we got in fourth grade. It wasn't just a simple border dispute. It was a chaotic, multi-ethnic explosion fueled by clashing constitutions, land speculation, and a dictator who honestly thought he was the "Napoleon of the West."

History is loud. It’s also complicated.

To understand why a bunch of American settlers and Mexican Tejanos decided to pick up rifles against the Mexican government, you have to look at the mess that was Mexico in the 1830s. Mexico had only recently won its own independence from Spain. It was a young, fragile nation trying to find its feet. To fill up its northern territory—the area we now call Texas—the government invited Americans to move in. They offered cheap land. There was a catch, though: you had to become a Mexican citizen and, at least on paper, be Catholic.

👉 See also: Supermax Prison Colorado Inmates: The Reality of Life Inside ADX Florence

Thousands of people took the deal. They were called Empresarios, led by guys like Stephen F. Austin. But by 1835, the vibe had shifted. Antonio López de Santa Anna, the President of Mexico, decided he didn’t like the federalist system that gave states power. He scrapped the Constitution of 1824. He basically declared himself the law. That was the spark.

The Constitutional Crisis Nobody Talks About

We often think the Texas Revolution started because Americans wanted to steal land. While land was definitely a factor, the initial fight wasn't actually for independence. It was a civil war. Many people in Texas, including the native Mexican residents known as Tejanos, were fighting to restore the 1824 Constitution. They wanted their rights back from a centralist government in Mexico City that felt a thousand miles away.

Imagine living in a place where the rules change overnight. One day you have a local legislature; the next, Santa Anna sends an army to tell you that your local government is dissolved. It's jarring. This is why people like Juan Seguín, a proud Tejano, fought alongside Jim Bowie and William B. Travis. They weren't fighting for the United States yet. They were fighting for Texas as a free Mexican state.

Of course, things escalated. Fast.

The first shots didn't happen at a fortress or a palace. They happened over a small bronze cannon in a town called Gonzales. The Mexican military wanted it back. The settlers told them to "Come and Take It." They even made a flag with a little drawing of the cannon on it. It’s arguably the most successful branding campaign in military history. From that moment on, there was no going back. Blood was in the water.

The Alamo: A Strategic Disaster Turned Myth

Let’s be real about the Alamo. Militarily, it was a mistake. Sam Houston, the commander of the Texian army, told Jim Bowie to blow the place up and leave. He didn't want his men trapped in an old mission that was never designed to hold off a professional army. But Bowie and Travis stayed.

For 13 days in early 1836, about 180 to 250 men held out against thousands of Mexican troops. It was brutal. It was cold. And honestly, it was a slaughter. When the walls finally fell on March 6, almost every defender was killed. Santa Anna thought this would terrify the rest of Texas into submission.

He was wrong.

The Alamo became a rallying cry. It turned a disorganized rebellion into a focused crusade. But while the Alamo gets all the movies, the Goliad Massacre was arguably more impactful. At Goliad, over 300 Texian prisoners were executed under Santa Anna’s orders after they had already surrendered. If the Alamo was a tragedy, Goliad was a war crime. It convinced the settlers that they weren't just fighting for politics anymore; they were fighting for their lives.

The Runaway Scrape and the 18-Minute Battle

While Santa Anna was marching east, the rest of Texas was in a blind panic. This period is known as the Runaway Scrape. Thousands of families abandoned their homes, burning what they couldn't carry, fleeing toward the Louisiana border. It was a mess. Roads were muddy. Disease was everywhere. Sam Houston’s army was also retreating, and his own men were starting to think he was a coward.

Houston wasn't a coward; he was a student of history. He knew he couldn't beat Santa Anna in a conventional European-style battle. He needed the Mexican army to get tired, stretched thin, and overconfident.

He got exactly what he wanted at San Jacinto.

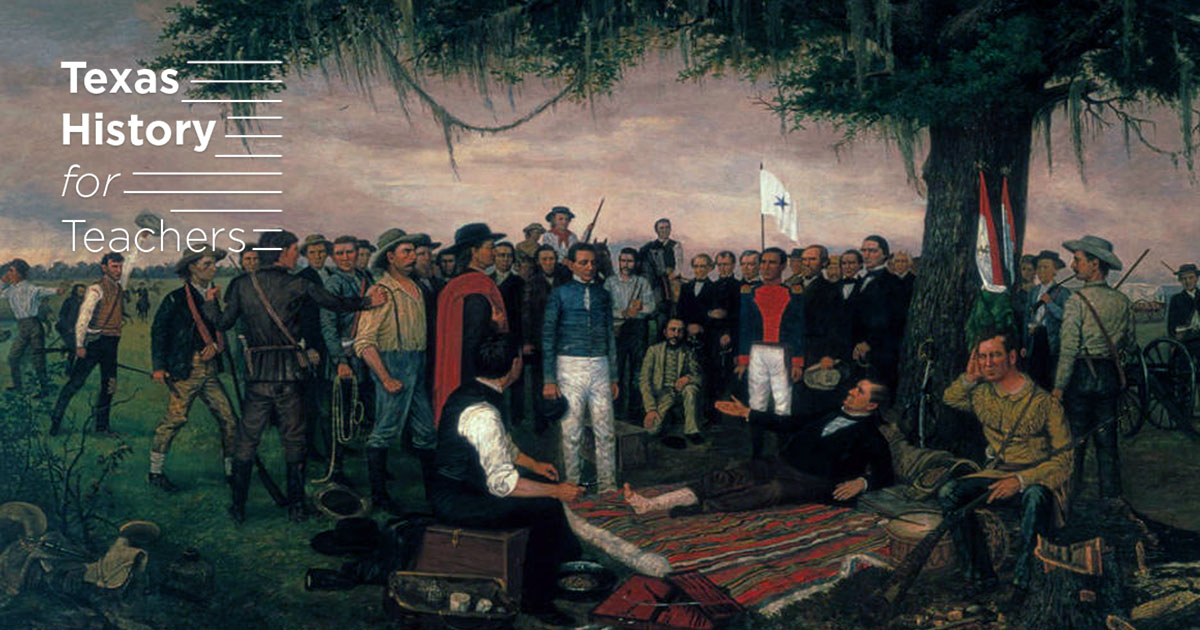

On April 21, 1836, Santa Anna’s army settled down for a siesta near the San Jacinto River. They didn't put out enough scouts. They thought Houston was cornered. In the middle of the afternoon, the Texian army—screaming "Remember the Alamo!" and "Remember Goliad!"—charged across the open field.

The battle lasted 18 minutes.

Eighteen minutes. That’s shorter than a sitcom episode. By the time it was over, hundreds of Mexican soldiers were dead or captured. Santa Anna himself escaped the initial carnage by hiding in the tall grass, but he was caught the next day wearing a common soldier's uniform. He was only found out because his own men started saluting him and calling him "El Presidente" when he was brought into camp.

The Slavery Question and the Complicated Legacy

You can't talk about the Texas Revolution without talking about slavery. It’s the elephant in the room that many older history books try to ignore. Mexico had moved to abolish slavery, while many of the American settlers in Texas were from the South and brought enslaved people with them.

The desire to protect the institution of slavery was absolutely a motivating factor for many of the white settlers. If Texas stayed under Mexican rule, their "property" was at risk. Does this mean the whole revolution was just about slavery? No. But does it mean the revolution was purely about "liberty"? Also no. It’s a Venn diagram of motivations. You had people fighting for land, people fighting for constitutional rights, people fighting for the right to own other humans, and people just caught in the crossfire.

Even after the victory at San Jacinto, Texas wasn't a state. It was a republic. For nine years, the Republic of Texas was its own country. It had its own currency (which was basically worthless), its own navy (which was tiny), and a whole lot of debt. Most people in Texas wanted to join the U.S. immediately, but Washington was hesitant. Adding Texas meant adding a massive slave state, which would upset the delicate balance of power in the American government.

Why the Revolution Still Matters Today

The Texas Revolution fundamentally changed the map of North America. Without it, the Mexican-American War probably doesn't happen. Without that war, the U.S. doesn't get California, Arizona, New Mexico, or Nevada. The entire geopolitical landscape of the world would look different today if a few hundred guys hadn't charged a camp at San Jacinto.

It also left Texas with a unique identity. It’s the only state that was its own recognized nation before joining the Union (sorry, Vermont and Hawaii, but the scale was different). That "independent streak" you hear about in Texas politics today? It started in the mud and blood of 1836.

But we need to remember the people who got squeezed out. The Tejanos who fought for independence often found themselves treated as second-class citizens in the new Republic. Native American tribes like the Comanche and Cherokee saw their land rights evaporate as the new government expanded. History is a series of trade-offs.

Real-World Takeaways and Next Steps

If you want to truly understand this era beyond the myths, here is how you should approach it:

- Visit the San Jacinto Battleground: Most people go to the Alamo, but San Jacinto is where the war was actually won. The monument there is taller than the Washington Monument (Texas had to one-up everyone, obviously).

- Read the Primary Sources: Check out the Memoirs of Juan Seguín. It provides a heartbreaking perspective of a man who fought for Texas but felt like a stranger in his own land afterward.

- Look at the 1824 Constitution: Compare it to the 1836 Texas Constitution. You’ll see exactly what the settlers were trying to keep and what they were trying to change.

- Acknowledge the Nuance: Understand that Stephen F. Austin was a moderate who spent months in a Mexican prison trying to avoid war before he finally gave in.

- Trace the Geography: If you're in Texas, follow the path of the "Runaway Scrape." It puts the sheer scale of the terror and the landscape into perspective.

The Texas Revolution wasn't a clean, choreographed event. It was a gritty, high-stakes gamble that almost failed a dozen times. Knowing the flaws and the darker parts of the story doesn't make the history less interesting; it makes it more human.

You should look into the "Archives War" next if you want to see how chaotic the Republic years actually were. It involves a boarding house owner firing a cannon at government officials in Austin. Seriously.