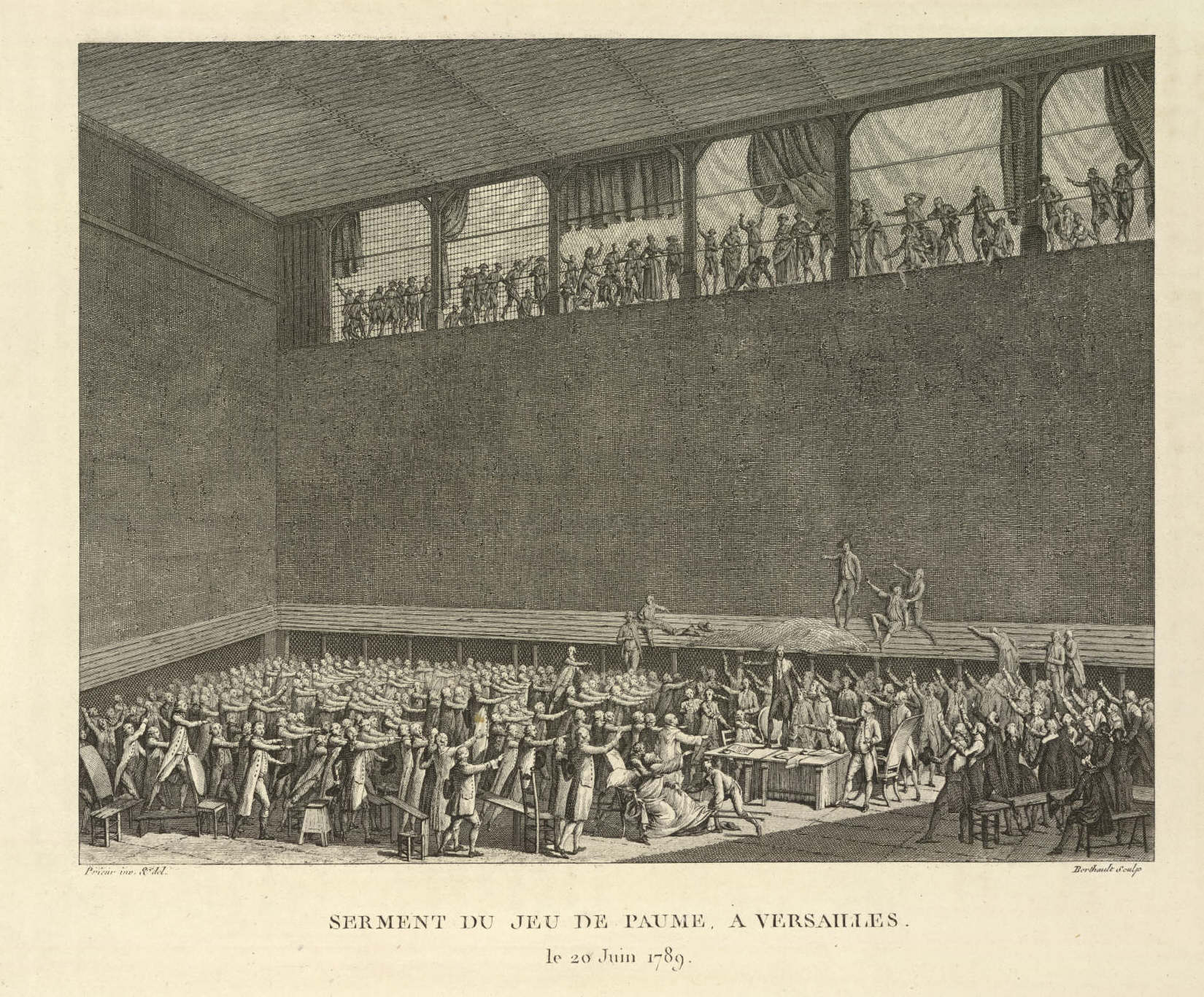

History books usually make it sound like the French Revolution was just a bunch of angry people storming the Bastille, but honestly? It really started inside a drafty, echoing indoor sports arena. The Tennis Court Oath wasn't just some polite legal disagreement. It was a full-blown act of treason. If you were standing in that room on June 20, 1789, you weren't just watching a meeting; you were watching a group of men gamble their lives against the most powerful monarchy in Europe.

They were locked out.

That’s the part people forget. King Louis XVI hadn't planned on a revolution starting that Saturday. He just wanted to stop the Third Estate—the commoners—from meeting and making demands. He claimed the Salle des États, their usual hall at Versailles, was closed for "repairs." It was a clumsy, passive-aggressive move. It backfired spectacularly.

Why the Third Estate Went Rogue

To understand why the Tennis Court Oath matters, you have to realize how rigged the system was. France was broke. Decades of wars and a terrible harvest had left people starving, but the nobility and the clergy (the First and Second Estates) didn't want to pay taxes. They wanted the poor to cover the bill.

When the Estates-General met in May 1789, the voting was stuck. Each estate got one vote. This meant the nobles and the church could always outvote the commoners 2-to-1, even though the commoners represented 98% of the population. It was a joke.

Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, a clergyman who actually sided with the commoners, wrote a pamphlet titled What is the Third Estate? His answer? Everything. He argued they didn't need the other two groups to govern. This was the intellectual spark. On June 17, they renamed themselves the National Assembly. They were the state now.

That Famous Rainy Morning

When the deputies showed up on June 20 and found the doors locked and guarded by soldiers, they didn't go home. It was raining. They needed cover. A deputy named Guillotin—yes, that Guillotin, though he hadn't invented the execution machine yet—suggested they move to a nearby indoor tennis court.

💡 You might also like: Wisconsin Judicial Elections 2025: Why This Race Broke Every Record

The Jeu de Paume.

It wasn't a tennis court like we think of today with green grass or hard clay. It was a high-walled, rectangular room for "real tennis," a game played by hitting a ball against the walls. It was loud. It was cramped. There were no chairs. Most of the 576 deputies had to stand for hours.

Jean-Sylvain Bailly, the man who would later become the Mayor of Paris, stood on a makeshift table. He was the one who read the oath. It basically said they wouldn't leave, and they wouldn't stop meeting, until they had written a formal constitution for France.

Only one guy refused to sign. Joseph Martin-Dauch. He thought they were moving too fast. He almost got mobbed by the others, but Bailly protected him, showing that even in a revolution, there was a desperate attempt to keep some semblance of order.

Jacques-Louis David and the Power of Propaganda

If you've ever seen the famous painting of the Tennis Court Oath, you’re looking at a bit of a lie. Jacques-Louis David, the "it" artist of the era, started a massive canvas to commemorate the event.

He painted it to look like a holy moment. There's wind blowing through the curtains like the breath of God. You see a monk, a priest, and a Protestant pastor hugging in the foreground to show "national unity." In reality, those groups were still biting each other's heads off.

📖 Related: Casey Ramirez: The Small Town Benefactor Who Smuggled 400 Pounds of Cocaine

David never actually finished the painting. Why? Because the Revolution moved too fast. By the time he was halfway done, many of the "heroes" in the painting had been branded traitors and sent to the guillotine. Politics shifted like sand. Painting a static "heroic" moment was impossible when today's patriot was tomorrow's headless body.

The King Flinches

What happened next is kinda wild. Louis XVI finally realized he couldn't just lock doors to stop a movement. He ordered the other two estates to join the National Assembly a week later. But he was also secretly moving thousands of troops into Paris.

He was playing both sides.

The Tennis Court Oath was the moment the deputies realized they had the moral high ground. They had defied the King and he hadn't arrested them immediately. That's a huge psychological win. It proved the "Divine Right of Kings" was a crumbling concept. If the King’s will could be ignored by a bunch of lawyers in a sports gym, was he really chosen by God?

The Legacy of the Oath

We see echoes of this moment in every modern democracy. The idea that a government's legitimacy comes from the people, not the person wearing the crown, solidified in that room. It led directly to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

But it wasn't all sunshine and "liberté."

👉 See also: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

The oath also set a precedent for radicalization. Once you've committed treason—which is what the oath was—you can't really go back. You’re all-in. This "all-or-nothing" mentality eventually spiraled into the Reign of Terror. Robespierre, who was one of the guys standing in that tennis court, would eventually oversee the execution of thousands of his fellow citizens.

What You Can Learn from the Jeu de Paume

History isn't just dates; it's about how people react under pressure. The Tennis Court Oath shows that when systems refuse to bend, they break.

If you're looking for the "so what" of this whole event, here it is:

- Symbolism matters more than settings. A gym can be a palace if the right words are spoken in it.

- The "middle ground" disappears quickly. Once the National Assembly declared themselves the sole power, the King was essentially a figurehead or an enemy. There was no third option.

- Bureaucracy is a terrible weapon. Locking a door to stop a revolution is like trying to stop a flood with a Post-it note.

How to Visit the Site Today

If you find yourself in Versailles, don't just spend all your time in the Hall of Mirrors. The Salle du Jeu de Paume is tucked away on a side street (Rue du Jeu de Paume). It’s been restored and functions as a museum.

You can stand on the same floor where the deputies stood. It’s surprisingly small. Seeing the scale of the room makes the event feel much more human. It wasn't a grand stage; it was a desperate, sweaty, loud room full of men who were terrified but determined.

Next Steps for History Buffs:

Check out the primary source documents from the Estates-General. Specifically, look for the "Cahiers de Doléances"—the lists of grievances written by ordinary French people in 1789. They give you a gritty, non-romanticized look at what people actually wanted: bread, fair taxes, and an end to the crushing weight of the nobility. Then, compare the text of the Tennis Court Oath to the opening of the U.S. Constitution; the parallels in the language of "The People" are unmistakable.

The French Revolution didn't start with a bang or a guillotine blade. It started with a promise made in a sports hall. Without that oath, the Bastille might have just stayed a boring prison, and Louis XVI might have died in his bed. Instead, a rainy Saturday changed the map of the world forever.