Perspective is a funny thing. You might think you’re being a hero, a savior, or just a really good friend, while the person on the receiving end thinks you’re a total nightmare. Honestly, that’s the entire heartbeat of The Tale of Two Beasts by Fiona Roberton. It’s a picture book, sure. But if you think it’s just for kids, you’re kinda missing the point. It’s a masterclass in empathy and the messy reality of how two people can experience the exact same event in completely different ways.

Most stories give you one narrator. We follow them, we trust them, and we assume they’re right. Roberton flips the script.

She gives us a "Part One" and a "Part Two." It’s a simple structural choice that feels revolutionary when you’re reading it to a child—or even when you’re looking at it as an adult. One side sees a rescue; the other sees a kidnapping. It’s brilliant.

What Actually Happens in The Tale of Two Beasts?

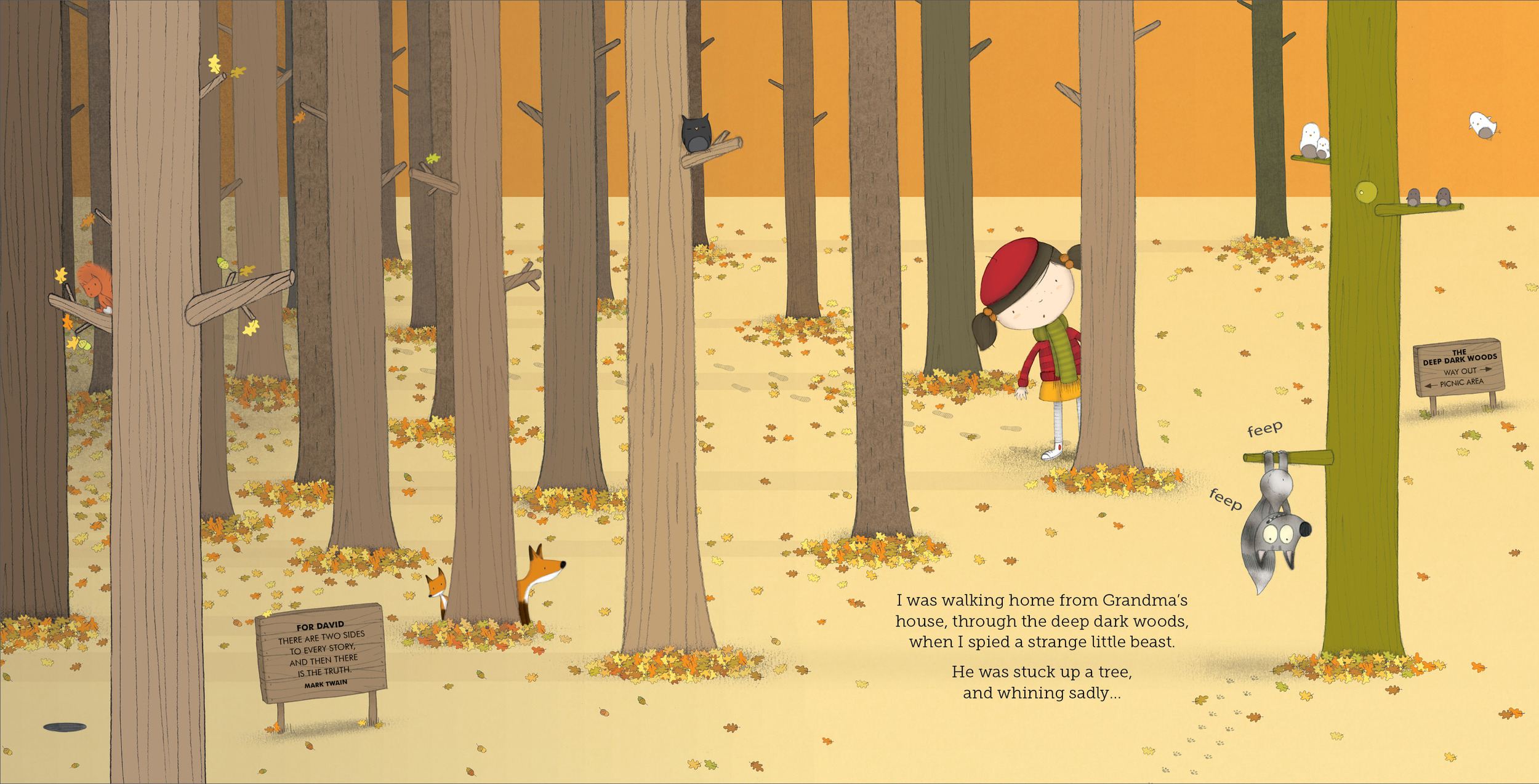

The plot is deceptively straightforward. A little girl is walking through the Deep Dark Woods when she finds a "strange beast" stuck in a tree. She decides it needs her help. She takes it home, dresses it up, feeds it, and shows it off. To her, this is a rescue mission. She's the protagonist. She's the "good guy."

Then the book resets.

In the second half, we see the story from the beast's point of view. Suddenly, the "Deep Dark Woods" is just "Home." The "rescue" is a terrifying abduction by a "terrible beast" (the girl). The fancy sweater she put on him is a stifling, itchy cage. The "delicious" food is unrecognizable. It’s the same sequence of events, but the emotional color palette shifts from warm and fuzzy to cold and chaotic.

The Girl’s Version: The "Little Beast"

The girl sees herself as a benevolent caregiver. She finds a small, green, squirrel-like creature and assumes it’s lost and lonely. She wraps it in a scarf. She brings it to her house. She names it. This is a classic human impulse—we see something "wild" and we want to domesticate it because we think our version of comfort is universal.

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

She’s not being mean. That’s the nuance. She’s being "kind," but it’s an unasked-for kindness. It’s a projection of her own needs onto another living being.

The Beast’s Version: The "Terrible Beast"

When the beast takes over the narration, the tone shifts. The girl is huge. Her house is loud. The hat she makes him wear is embarrassing. He’s not a pet; he’s a captive. He spends the entire time looking for an exit. When he finally escapes back to his woods, he realizes something unexpected: even though the girl was annoying, she was... kinda nice?

This is where Roberton's writing shines. It doesn't end with a "one person is right and one is wrong" moral. It ends with a bridge. The beast returns to the girl, not because he wants to be a pet, but because they’ve found a middle ground. They play on his terms, in his woods.

Why This Book Ranks So High for Educators and Parents

You’ll see The Tale of Two Beasts on almost every primary school reading list across the UK and many parts of the US. Why? Because it’s the perfect "anchor text" for teaching Inference and Point of View.

In the world of literacy education, teachers use this book to explain "The Reliable Narrator." Kids are naturally egocentric; they see the world through their own eyes. Roberton forces them to step outside that. She uses visual cues—the girl’s bright yellow coat versus the beast’s green fur—to anchor the identity of the characters even as their roles shift from "hero" to "villain" depending on who's talking.

The illustrations are minimalist but incredibly expressive. Look at the beast’s eyes when the girl is "rescuing" him. He’s bug-eyed with fear. The girl, however, is smiling. This disconnect between the text (which says they are having fun) and the art (which shows the beast is miserable) is a sophisticated storytelling technique called "counterpoint."

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

Common Misconceptions About the Story

A lot of people think the beast is just being ungrateful. I've heard parents say, "She gave him a home, why is he complaining?"

That misses the subtext.

The book is actually a subtle critique of colonialism or at least the "savior complex." It asks: who defines what a "good life" looks like? To the girl, a good life is indoors with hats and snacks. To the beast, it’s hanging upside down in a damp forest. Neither is inherently better, but imposing one on the other is a form of "beastliness."

- Fact: Fiona Roberton is both the author and illustrator.

- Fact: The book was published by Hodder Children's Books in 2014.

- Fact: It won the Hamptons Children's Literature Award and was shortlisted for the Stockport Children's Book Award.

The "beast" isn't actually a monster. He looks like a cross between a squirrel, a cat, and a lizard. This ambiguity is intentional. If he looked like a dog, we’d assume he belonged in a house. Because he’s a "beast," he belongs to the wild.

The Art of the Ending (Spoilers, Kinda)

The ending is what keeps people coming back. The beast escapes. He’s free. He’s happy. But then he looks at the scarf the girl gave him. It’s a piece of her. He realizes that while her "rescue" was a disaster, her intent was connection.

So he goes back.

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

But he doesn't go back to live in her house. They meet in the middle. This is the "Third Way." It’s not your way, and it’s not my way. It’s our way. It’s a surprisingly deep resolution for a book with less than 500 words.

Applying the Lesson of Two Beasts to Real Life

If you’re a manager, a partner, or a friend, the "Two Beasts" trap is everywhere. You think you’re helping a coworker by taking over their project. You’re the "Good Girl." They think you’re micromanaging and stealing their autonomy. They see you as the "Terrible Beast."

How do you fix it? You do what the characters do at the end of the book. You stop talking and start observing.

- Acknowledge the Gap: Your "helpful" might be someone else's "hurtful."

- Swap the Scarf: Try to see the "itchy hat" in your own behavior.

- Find the Deep Dark Woods: Meet people where they are comfortable, not just where you are comfortable.

The beauty of The Tale of Two Beasts is that it doesn't lecture. It just shows. It shows that two truths can exist at the same time. The girl is kind AND the girl is a kidnapper. The beast is a victim AND the beast is a friend.

Next time you’re in a disagreement, ask yourself: which part of the book am I in right now? Am I in Part One, where I’m the hero of my own story? Or am I brave enough to read Part Two and see how I might be the beast in someone else’s?

Actionable Steps for Parents and Readers

If you're reading this with a child, don't just finish the book and put it away. Try these specific tweaks to the reading experience to get the most out of it:

- The Cover Flip: Before starting Part Two, ask: "How do you think the squirrel feels?" Then see if their answer changes by the end.

- The Hidden Details: Look at the background characters. There are birds and other forest creatures watching the "kidnapping." Their expressions often mirror the beast’s, not the girl's.

- The Rewriting Exercise: Pick a different event—like a birthday party or a trip to the dentist—and try to tell it from two opposite perspectives. It’s harder than it looks.

Fiona Roberton created something lasting here because she didn't talk down to her audience. She acknowledged that life is a matter of where you stand. And honestly? We could all use a little more of that "Part Two" thinking.

To truly master the themes of this story, start by observing your next minor conflict through the lens of the "other beast." Notice the specific moment where your "kindness" might feel like an "itchy hat" to someone else. Adjusting your approach based on their environment—the "Deep Dark Woods"—rather than your own "house" is the fastest way to build a genuine connection. This isn't just about a picture book; it's about the fundamental mechanics of human empathy. Once you see the "terrible beast" in yourself, you can finally start being a real friend.