New York City in the seventies was a different beast. It was louder, dirtier, and—if you believe the movies—a lot more dangerous. Among the sea of crime dramas from that era, one story stands out for its sheer, claustrophobic tension. I’m talking about The Taking of Pelham 123. Whether you’re a fan of the original 1973 novel by John Godey, the iconic 1974 film, or even the high-octane Tony Scott remake from 2009, there’s something about a hijacked subway train that taps into a very specific kind of urban anxiety.

It’s the nightmare scenario for any commuter. You’re underground. You’re in a steel tube. You have nowhere to go.

What makes The Taking of Pelham 123 so effective isn't just the heist itself. It’s the logistics. It’s the clash between the cold, calculating hijackers and the weary, cynical employees of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). This isn't a story about superheroes. It’s a story about guys in thick glasses, guys with bad ties, and a city that is perpetually five minutes away from a nervous breakdown.

The Original 1974 Masterpiece: Realism Over Flash

If you haven't seen the 1974 version directed by Joseph Sargent, you’re missing out on arguably the best thriller of that decade. Walter Matthau plays Zachary Garber, an MTA lieutenant who looks like he just woke up from a nap and desperately needs a coffee. He’s the opposite of a modern action hero. He’s rumpled. He’s sarcastic.

The plot is deceptively simple: four men, using the pseudonyms Mr. Blue, Mr. Green, Mr. Grey, and and Mr. Brown, board a downtown 6 train. They uncouple the lead car, hold the passengers hostage, and demand $1 million. If the money isn't delivered in exactly one hour, they start killing people. One by one.

The tension in this version comes from the dialogue. It's snappy. It feels authentic to New York. When the hijackers call the Transit Authority Command Center, the workers don't react with cinematic horror; they react with annoyance because this is messing up the schedule. That's the most "New York" thing ever recorded on film.

Robert Shaw plays Mr. Blue with a terrifying, British stillness. He’s a mercenary who doesn't care about the city or the people in it. The contrast between his icy precision and Matthau’s frantic, blue-collar navigation of city bureaucracy is where the magic happens. Honestly, the movie works because it feels like it could actually happen. Or, at least, it felt that way in 1974 when the city was broke and the subways were covered in graffiti.

👉 See also: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

Comparing the 1974 and 2009 Versions

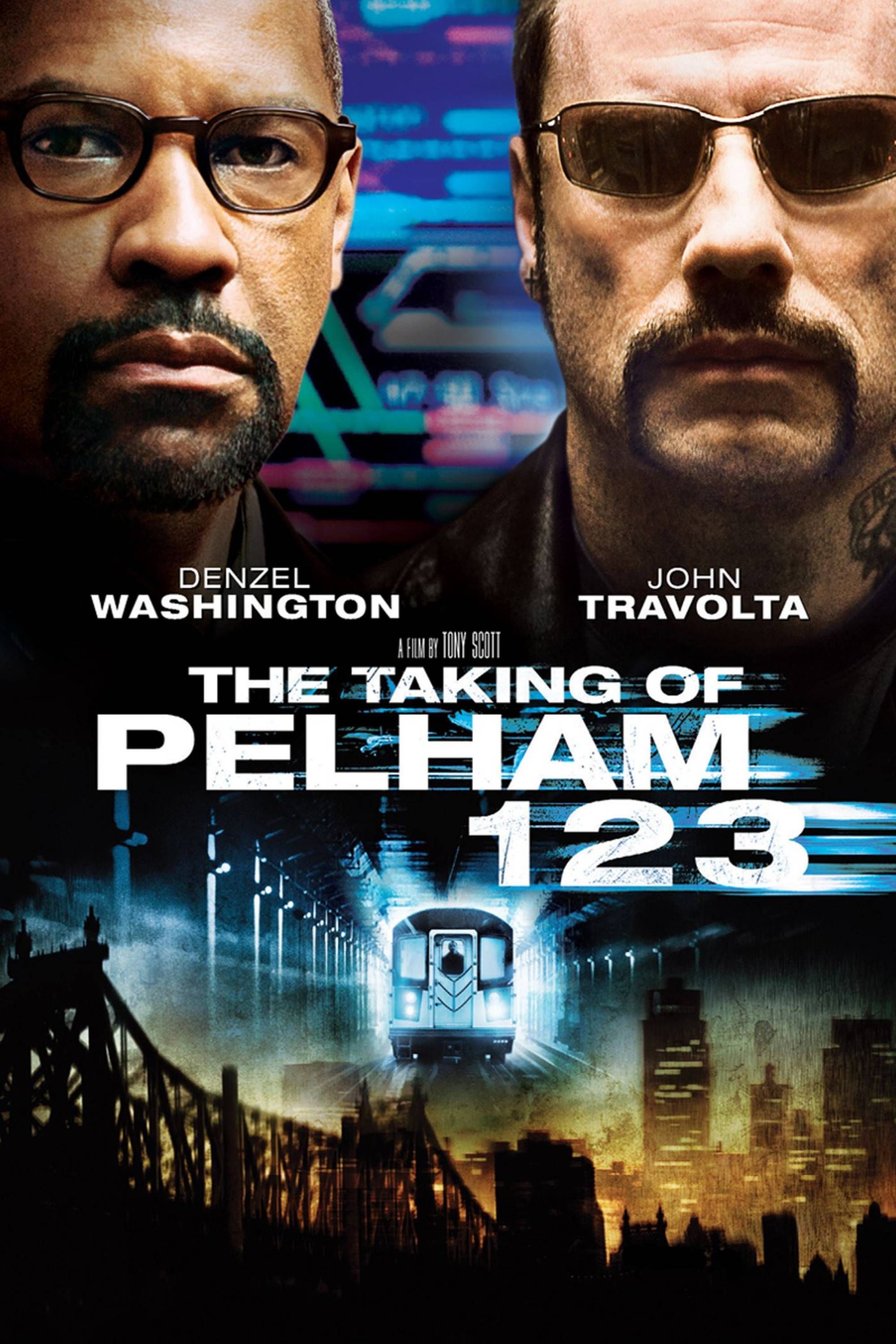

Fast forward to 2009. Tony Scott, the master of the "shaky cam" and high-saturation visuals, decided to bring The Taking of Pelham 123 into the 21st century. This time, we have Denzel Washington as Walter Garber (now a disgraced dispatcher) and John Travolta as Ryder, the lead hijacker.

The stakes changed. In 1974, they wanted a million dollars. In 2009, with inflation and the scale of modern greed, the demand jumped to $10 million. But the biggest shift wasn't the money; it was the vibe.

The 2009 version is loud. It’s sweaty. Travolta’s Ryder is a manic, profanity-spewing villain who feels like he’s constantly on the verge of an explosion. Denzel, as always, is incredible, bringing a grounded, soulful weight to a man who just wants to survive the day. However, many purists argue that the remake loses the "city-as-a-character" feel that made the original so special.

In the original, the city's incompetence is a plot point. The police car crashes. The Mayor is sick in bed, more worried about his approval ratings than the hostages. In the remake, it feels more like a personal battle between two men. Both are valid, but if you want the "real" Taking of Pelham 123 experience, the 70s version wins every time.

The Logistics of a Subway Hijacking

How do you even stop a subway train? This is the technical hurdle that the story handles so well. You can't just drive it away like a getaway car. You're on tracks. There are signals. There are power grids.

The hijackers in the story utilize the "dead man's feature," a safety mechanism designed to stop the train if the motorman becomes incapacitated. By manipulating these technical quirks of the New York City Transit system, the criminals create a stalemate. They know the system better than the police do.

✨ Don't miss: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

Interestingly, after the book and movie became popular, there were genuine concerns within the MTA that someone might try to copy the crime. The "Pelham" of the title refers to the Pelham Bay Park station in the Bronx, where the 6 train originates. The "123" is the time the train departed: 1:23 PM. It’s a mundane detail that becomes a symbol of terror.

Why We Are Still Obsessed With This Story

Urban legends and heist films usually rely on the "big score"—robbing a vault or a casino. The Taking of Pelham 123 is different because it’s so intimate. We’ve all been on a crowded train. We’ve all looked at the person sitting across from us and wondered who they are.

The story strips away the anonymity of the city. For those sixty minutes, the conductor, the motorman, the socialite, and the homeless man are all the same. They are just leverage.

Moreover, the ending of the 1974 film is legendary. No spoilers here, but it involves a sneeze. A simple, human, uncontrollable sneeze. It’s one of the most satisfying payoffs in cinema history because it doesn't involve a massive explosion or a shootout. It involves a detail.

The Cultural Legacy: From Tarantino to Beastie Boys

You can see the fingerprints of this story everywhere. Quentin Tarantino famously used the "color names" for his thieves in Reservoir Dogs (Mr. White, Mr. Orange, etc.), which was a direct homage to the hijackers in Pelham.

The Beastie Boys even sampled dialogue from the film. It has become a shorthand for a specific kind of tough, gritty, New York cool. It’s about the "front" people put up in the city and what happens when that front is shattered by a crisis.

🔗 Read more: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Survival Lessons from the Pelham Scenario

While you’re (hopefully) never going to be on a hijacked subway car, the story offers some surprisingly practical insights into human behavior under pressure.

- Communication is everything. In both versions, the negotiator's ability to keep the lead hijacker talking is the only thing preventing a massacre.

- Bureaucracy can be a weapon. The slow movement of the city's red tape actually works in the favor of the authorities at several points, buying them time.

- The "Grey" Areas. Not every villain is a monster, and not every hero is a saint. Garber in the 2009 version has a murky past involving a bribe. This makes the stakes feel more "real" than a standard good-vs-evil trope.

What to Watch or Read First

If you’re new to this world, here is the recommended order of operations:

- Read the 1973 novel by John Godey. It goes into much more detail about the lives of the hostages. You get their backstories, which makes the tension almost unbearable.

- Watch the 1974 film. It’s the gold standard. The score by David Shire is a jazz-fusion masterpiece that perfectly captures the frantic energy of NYC.

- Check out the 2009 remake. Watch it for the performances of Denzel Washington and James Gandolfini (who plays the Mayor). It’s a fun, fast-paced action flick even if it lacks the grit of the original.

There was also a 1998 made-for-TV movie starring Edward James Olmos. It’s... fine. But it doesn't have the budget or the style of the other two, so it's mostly for completists.

Essential Takeaways for Fans of the Genre

If you want to understand the mechanics of urban thrillers, look at how The Taking of Pelham 123 uses the environment. The screeching brakes, the dark tunnels, and the flickering lights aren't just background—they are the plot.

The next time you’re standing on a subway platform and you see the lights of the 6 train approaching, you’ll probably think about it. You’ll think about Mr. Blue. You’ll think about the $1 million. And you’ll definitely check to see if anyone is wearing a suspicious hat and glasses.

To dive deeper into this specific sub-genre of "New York in the 70s" cinema, your next logical steps should be looking into The French Connection (1971) or Serpico (1973). These films share the same DNA: a city on the edge, captured with a raw, unfiltered lens. If you’re a writer or a filmmaker, study the 1974 Pelham script—it’s a masterclass in how to manage a large ensemble cast in a single, confined location without ever losing the momentum of the story.