You’ve probably seen it. That weird, slightly unsettling room where the fireplace looks like a nose and the curtains are golden hair. It's the Salvador Dalí Mae West face—a piece of art so iconic it basically defined the Surrealist movement’s obsession with celebrity culture before Andy Warhol was even a teenager. But honestly? Most people look at it and just see a funky room. They miss the chaotic, obsessive, and surprisingly technical story behind why a Spanish painter decided to turn a Hollywood sex symbol into a piece of furniture.

It wasn't just a whim. Dalí was obsessed. He didn't just want to paint Mae West; he wanted to inhabit her.

Why Salvador Dalí Chose Mae West (And Why It Wasn't Just About the Hair)

In the mid-1930s, Mae West was the most scandalous woman in the world. She was the queen of the double entendre, a woman who wrote her own plays and landed in jail for "corrupting the morals of youth." To the Surrealists, she was a walking, talking dream. She represented a raw, unfiltered sexual power that bypassed the "boring" logic of the era. Dalí, who lived for provocation, saw her as the ultimate canvas.

He didn't start with a giant room. He started with a small gouache on a newspaper scrap.

The original 1934 work, titled Face of Mae West Which May Be Used as a Surrealist Apartment, is actually quite tiny. It's a collage. He took a photo of West and began sketching over it, reimagining her features as architectural elements. The eyes became framed pictures of Paris. The nose? A fireplace with logs for nostrils. And then there were the lips. Those famous, pouty lips became a sofa. It was a joke that turned into a masterpiece.

The Paranoiac-Critical Method in Action

Dalí had this thing he called the "paranoiac-critical method." Sounds fancy, right? Basically, it’s the ability to look at one thing and see two. It’s like when you look at a cloud and see a dog, but Dalí did it with everything. In the case of the Salvador Dalí Mae West portrait, he was training the viewer to see a face and a living space simultaneously. He wanted to break your brain.

💡 You might also like: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

He wasn't interested in a "nice" portrait. He wanted to show how our desires—specifically our obsession with fame—distort how we see reality. When we look at a celebrity, we don't see a human. We see a commodity. We see a "room" we want to live in. It’s deeply cynical if you think about it long enough, which most people don't because they're too busy taking selfies in the reproduction rooms.

From Paper to Reality: The Mae West Lips Sofa

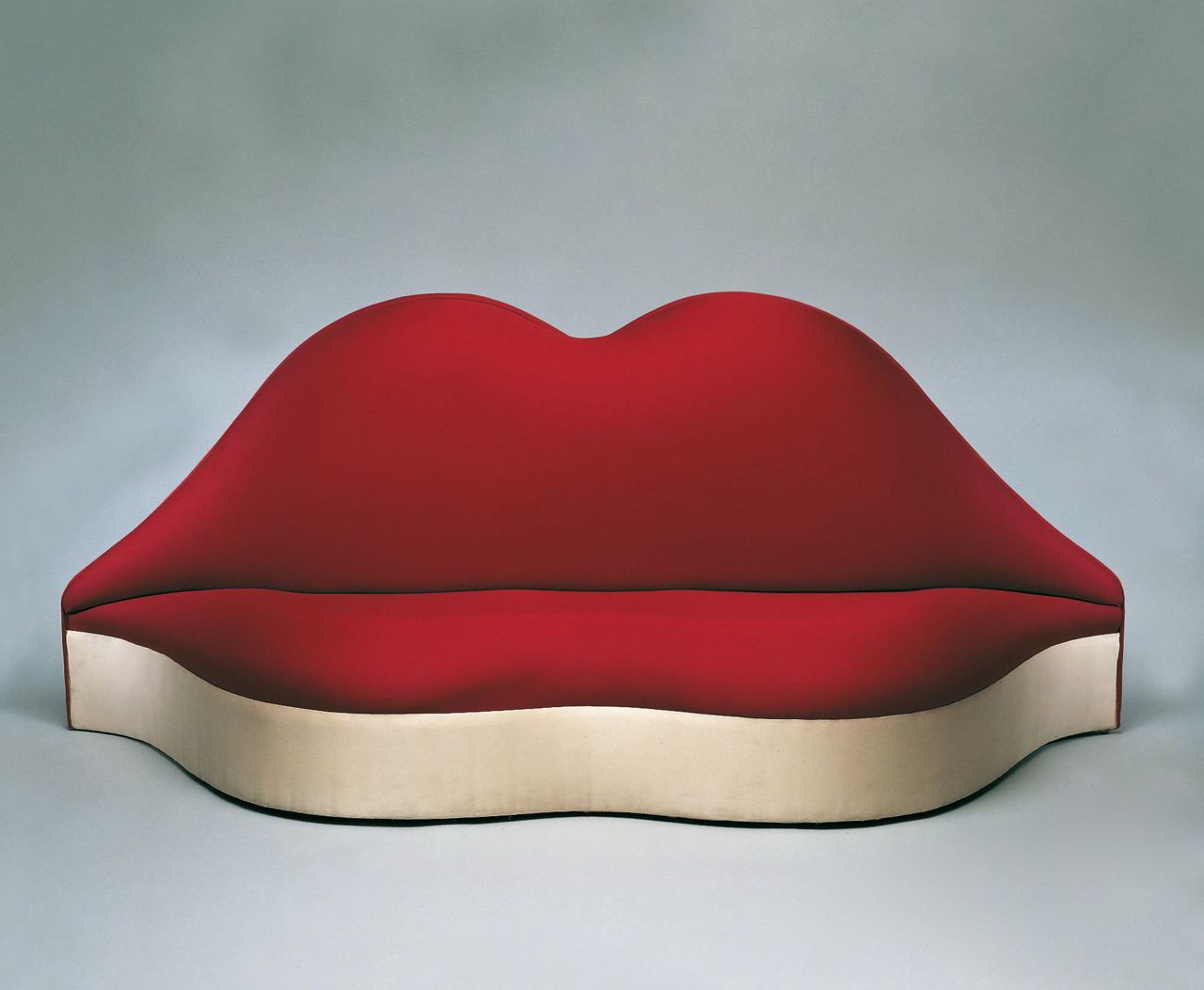

If you’ve ever walked into a high-end furniture store and seen a bright red sofa shaped like lips, you’re looking at a descendant of Dalí’s imagination. But the original sofa wasn't just "red."

Edward James, a wealthy British eccentric and Dalí’s patron, saw the drawing and said, "Let's actually build this." James was the kind of guy who had enough money to make fever dreams a reality. In 1937, they produced five versions of the sofa.

One was pink. One was red. But the most famous one? It was upholstered in a specific shade of "Shocking Pink" inspired by the perfume of Elsa Schiaparelli. This wasn't some soft, plush velvet meant for napping. It was a statement. Sitting on it was meant to be uncomfortable, a literal realization of sitting on a movie star’s mouth.

Dalí was very specific about the materials. He didn't want it to look like a normal couch. He wanted it to look like a mouth that might snap shut at any moment.

📖 Related: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

The Figueres Installation: Stepping Inside a Face

The most famous version of this work isn't the drawing or the sofa alone. It's the full-scale installation at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain. If you go there today, you have to climb a small set of stairs and look through a magnifying lens mounted between the legs of a giant camel (don't ask, it's Dalí) to see the face align perfectly.

From the floor, it looks like a pile of random furniture.

- A pair of fireplaces.

- Two grainy black-and-white photos of the Seine.

- A giant blonde wig made of actual yak hair (which apparently had to be treated for moths constantly).

- The red sofa.

But from that one specific vantage point? It’s her. It's Mae West. It’s a 3D optical illusion that forces you to acknowledge that your perspective is the only thing holding reality together.

The Technical Struggle

Creating that room wasn't easy. Oscar Tusquets, the architect who helped Dalí realize the vision in the 1970s, talked about how difficult it was to get the proportions right. If the "nose" was too far forward, the face fell apart. If the "lips" were too high, she looked deformed. It’s a masterclass in anamorphosis—the art of distorted projection.

Interestingly, Mae West herself reportedly wasn't that impressed. She was a woman of the theater and understood artifice, but she was also a business mogul who cared about her brand. Having her face turned into a room with a yak-hair wig probably wasn't the kind of PR she was used to.

👉 See also: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

Common Misconceptions About the Work

People often think Dalí and West were best friends. They weren't. Honestly, there’s very little evidence they spent significant time together at all. Dalí used her as an icon, a symbol, an archetype. To him, she was a "found object" of pop culture.

Another big mistake? Thinking the sofa was mass-produced during his lifetime. It wasn't. The original five were bespoke pieces for Edward James’s homes. It was only much later, in the 2000s, that the Dalí Foundation authorized the production of the "Dalilips" sofa using modern polyethylene rotation molding. The version you can buy today is plastic; the original was wood and wool. Huge difference in vibe.

Why This Still Matters in 2026

We live in an age of "Instagrammable" museums and immersive experiences. Every city has a "Van Gogh Experience" where they project stars on the walls. But the Salvador Dalí Mae West room was the original immersive art. Long before VR headsets and AI-generated filters, Dalí figured out that people didn't just want to look at art—they wanted to be inside it.

It also highlights our modern obsession with "filters." West was one of the first celebrities to meticulously curate her image. Dalí just took that curation to its logical, surreal extreme. He turned her into architecture. Today, we do the same thing when we turn ourselves into digital avatars. We are all building "rooms" out of our faces on social media.

How to Experience Dalí’s Mae West Today

If you actually want to see this stuff and not just look at low-res jpegs, you've got a few options. Each offers a completely different "vibe" of the work.

- The Dalí Theatre-Museum (Figueres, Spain): This is the holy grail. You get the full 3D room, the yak-hair wig, and the camel-lens experience. It’s crowded, it’s chaotic, and it’s exactly how Dalí wanted it.

- The Victoria and Albert Museum (London): They often house one of the original 1937 sofas. Seeing the actual fabric and the craftsmanship tells you a lot more about the 1930s surrealist movement than any textbook can.

- The Art Institute of Chicago: They hold the original 1934-35 gouache on newspaper. It’s tiny. Seeing it in person makes you realize how a massive architectural idea can start from a single, bored afternoon with a pair of scissors.

Actionable Takeaways for Art Lovers

- Look for the Anamorphosis: Next time you’re at a gallery, don't just stand in front of a piece. Move side-to-side. Dalí’s work is built on the idea that the "correct" view is often hidden at an angle.

- Study the Patrons: If you want to understand why weird art exists, look at the money. Researching Edward James provides a clearer picture of why the Mae West sofa exists than researching Dalí alone ever could.

- Trace the Influence: Look at modern furniture design. From the "Bocca" sofa of the 1970s to current Memphis Milano revivals, the DNA of the Mae West portrait is everywhere in contemporary interior design.

- Try the Method: Try the paranoiac-critical method yourself. Take a celebrity photo from a magazine and try to "see" a landscape or a room within their features. It’s a classic exercise for breaking through creative blocks.

The Salvador Dalí Mae West collaboration—even if it was a one-sided collaboration—remains the gold standard for how art can cannibalize celebrity culture and turn it into something permanent. It’s weird, it’s tacky, and it’s brilliant. Just don't expect the sofa to be comfortable. Art isn't supposed to be comfortable. It's supposed to be a room you can't stop thinking about.