Imagine arriving in Washington, D.C., on a chilly March afternoon, expecting a dignified parade, only to find yourself shoved, spat on, and essentially trapped in a sea of angry men. That was the reality for thousands of women on March 3, 1913. This wasn't just a walk down the street. The suffrage march of 1913—officially the Woman Suffrage Procession—was a calculated, risky, and frankly chaotic gamble that changed American politics forever.

It happened the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Alice Paul, the mastermind behind the whole thing, knew exactly what she was doing. She wanted to hijack the news cycle. She did. When Wilson arrived at the train station, he reportedly asked where everyone was. The answer? They were all over on Pennsylvania Avenue watching the women.

Why the Suffrage March of 1913 Almost Didn't Happen

Alice Paul and Lucy Burns were the "radicals" of the movement. They were tired of the slow, polite lobbying favored by the older generation of suffragists like Carrie Chapman Catt. They wanted a federal amendment, not a state-by-state slog. To get it, they needed a spectacle.

But getting permits wasn't easy. The D.C. police chief, Richard Sylvester, was less than helpful. He basically told them he couldn't guarantee their safety, which turned out to be a massive understatement. The organizers had to raise their own funds, recruit marchers from across the country, and design elaborate floats. They even had a lawyer, Inez Milholland, lead the parade on a white horse. It was theater. Pure, unadulterated political theater.

People forget how much internal drama there was, too. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was terrified Paul’s "British-style" tactics would backfire. They thought it was too aggressive. Too unladylike.

The Inez Milholland Effect

Inez Milholland is often the face of this march in history books. She wore a crown and a long white cape. She looked like a Greek goddess. Honestly, it was a brilliant PR move. It made the movement look powerful and ethereal rather than "shrill," which was the common insult of the day. But behind that image was a woman who was deathly ill; she actually died a few years later during a speaking tour, her last words reportedly being, "Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?"

The Ugly Reality of the Parade Route

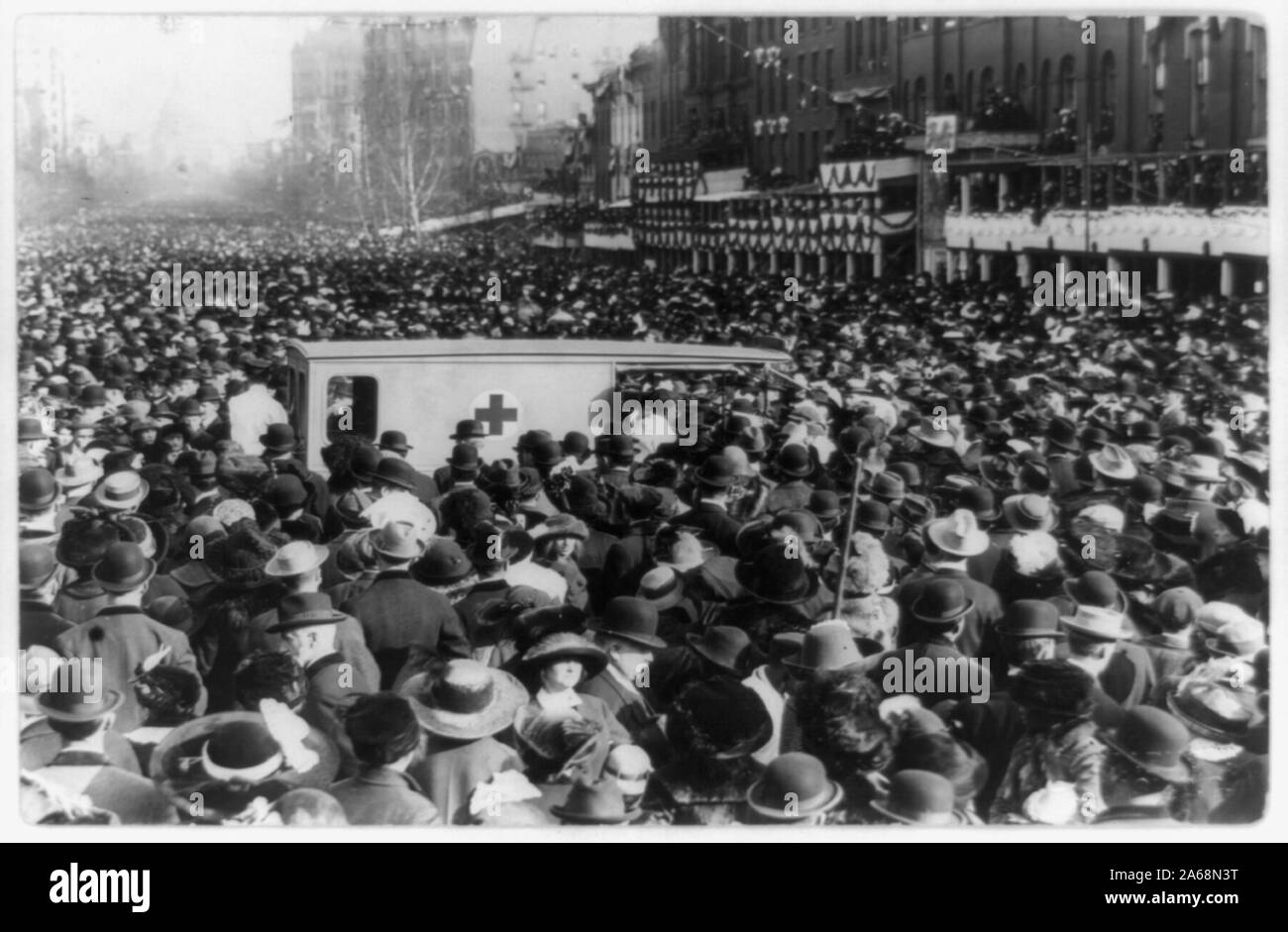

Everything started out fine. There were bands, floats, and banners. There were sections for female doctors, lawyers, and grocery clerks. It was a visual representation of women’s contribution to society. But as they moved toward the Treasury Building, the crowds—mostly men in town for the inauguration—began to close in.

🔗 Read more: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

The police did almost nothing.

Eyewitnesses later testified that officers were standing on the sidelines, laughing and telling the women they should go home to their kitchens. Marchers were tripped. They had burning cigars thrown at them. One woman, Genevieve Stone, later told a Senate hearing that she was "insulted in the most vile manner."

It was a riot.

By the time the cavalry was called in from Fort Myer to clear the way, over 100 people had been hospitalized. But here’s the kicker: the violence was the best thing that could have happened for the cause. The next day, the headlines weren't about Wilson. They were about the "suffrage outrages" in Washington.

The Racial Tension Nobody Likes to Talk About

We have to be real here. The suffrage march of 1913 was not a beacon of intersectionality. Alice Paul, in her attempt to keep Southern white suffragists on her side, tried to segregate the parade. She suggested that Black women should march at the back.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the legendary anti-lynching crusader and journalist, flatly refused.

💡 You might also like: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

She waited on the sidelines until the Illinois delegation passed by, and then she simply stepped into her spot with the white marchers. It was a quiet, badass act of defiance. Delta Sigma Theta, a newly formed sorority from Howard University, also marched. They were the only Black college organization there. They faced double the hostility—racism from the crowd and exclusion from the organizers.

The movement's history is messy. It’s important to acknowledge that the "victory" of suffrage was, for a long time, a victory mostly for white women. Black women in the South wouldn't see real voting protections until 1965.

The Political Fallout

Because of the chaos, the Senate held hearings. The police chief lost his job. But more importantly, the suffrage march of 1913 breathed new life into the 19th Amendment. It forced Woodrow Wilson to actually address the issue, even though he spent years trying to dodge it.

Alice Paul used the momentum to form the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, which later became the National Woman's Party. These were the women who eventually picketed the White House, went on hunger strikes, and were force-fed in prison. The 1913 march was the "gateway drug" to that more intense activism.

Key Figures You Should Know

- Alice Paul: The strategist. Think of her as the campaign manager who never sleeps.

- Lucy Burns: Paul’s right hand. She spent more time in jail than any other American suffragist.

- Mary Church Terrell: A founder of the NACW who marched with the Howard students.

- Helen Keller: Yes, that Helen Keller. she was supposed to speak but was too exhausted by the crowd's behavior.

Why Does This Still Matter in 2026?

You might think 1913 is ancient history. It’s not. The tactics used in that march—occupying public space, using visual branding, leveraging media outrage—are the blueprint for every major protest movement we see today.

Also, it's a reminder that rights aren't "given." They are taken. The women in 1913 weren't asking for a favor. They were demanding a right that had been denied for nearly a century. They dealt with physical assault and public shaming because they knew the status quo was unsustainable.

📖 Related: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

What We Get Wrong About the March

People often think this was a "nice" parade. It wasn't. It was a street fight. They also think it led directly to the vote. In reality, it took seven more years of grueling work, arrests, and a World War before the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920.

How to Apply These Lessons Today

If you're looking to understand modern political movements or even just how to organize a local community group, the 1913 march is a masterclass.

First, visuals matter. The white dresses and gold banners weren't just for show; they created a cohesive brand that looked great in the black-and-white newspapers of the time.

Second, location is everything. Marching in your hometown is great, but marching where the power is—Pennsylvania Avenue—changes the stakes.

Third, be prepared for the backlash. The organizers of the 1913 march knew there would be opposition, but they didn't let the fear of a riot stop the event. They used the opposition's bad behavior to win the "moral high ground" in the court of public opinion.

Real-World Steps to Take

- Visit the Belmont-Paul Women's Equality National Monument in D.C. if you're ever in the area. It was the headquarters for the National Woman's Party and houses the actual banners used in protests.

- Read the primary sources. Check out the Library of Congress digital archives. Looking at the original photos of the crowd closing in on the marchers gives you a visceral sense of the danger they were in.

- Research your local suffragists. Every state had its own battle. The national story is great, but the local chapters were the ones doing the door-to-door work that actually convinced congressmen to vote "yes."

- Support voting rights organizations. The fight started in 1913 hasn't actually ended. Issues like gerrymandering and voter ID laws are the modern frontiers of the same struggle.

The suffrage march of 1913 wasn't a "moment in time" so much as it was a massive crack in the dam. Once that happened, it was only a matter of time before the whole system of male-only voting collapsed. It was messy, it was brave, and it was deeply flawed. But it was undeniably effective.

Whether you're a history buff or just someone interested in how change actually happens, looking back at that chaotic day in D.C. tells you everything you need to know about the power of showing up.