You probably think of your small intestine as a smooth, slippery tube. Honestly, it’s anything but. If you could shrink down—Magic School Bus style—and take a walk through your own digestive tract, you’d find yourself trekking through a dense, velvety forest of millions of tiny, finger-like projections. This is the structure of a villus, and without it, you'd basically starve to death no matter how much pizza you ate.

It’s about surface area.

If the inside of your gut was a flat pipe, you wouldn’t have enough room to soak up the nutrients from your lunch. By folding the lining into millions of these little villi (that's the plural of villus), your body expands its internal real estate to the size of a tennis court. It’s a massive engineering feat packed into a space the size of a garden hose.

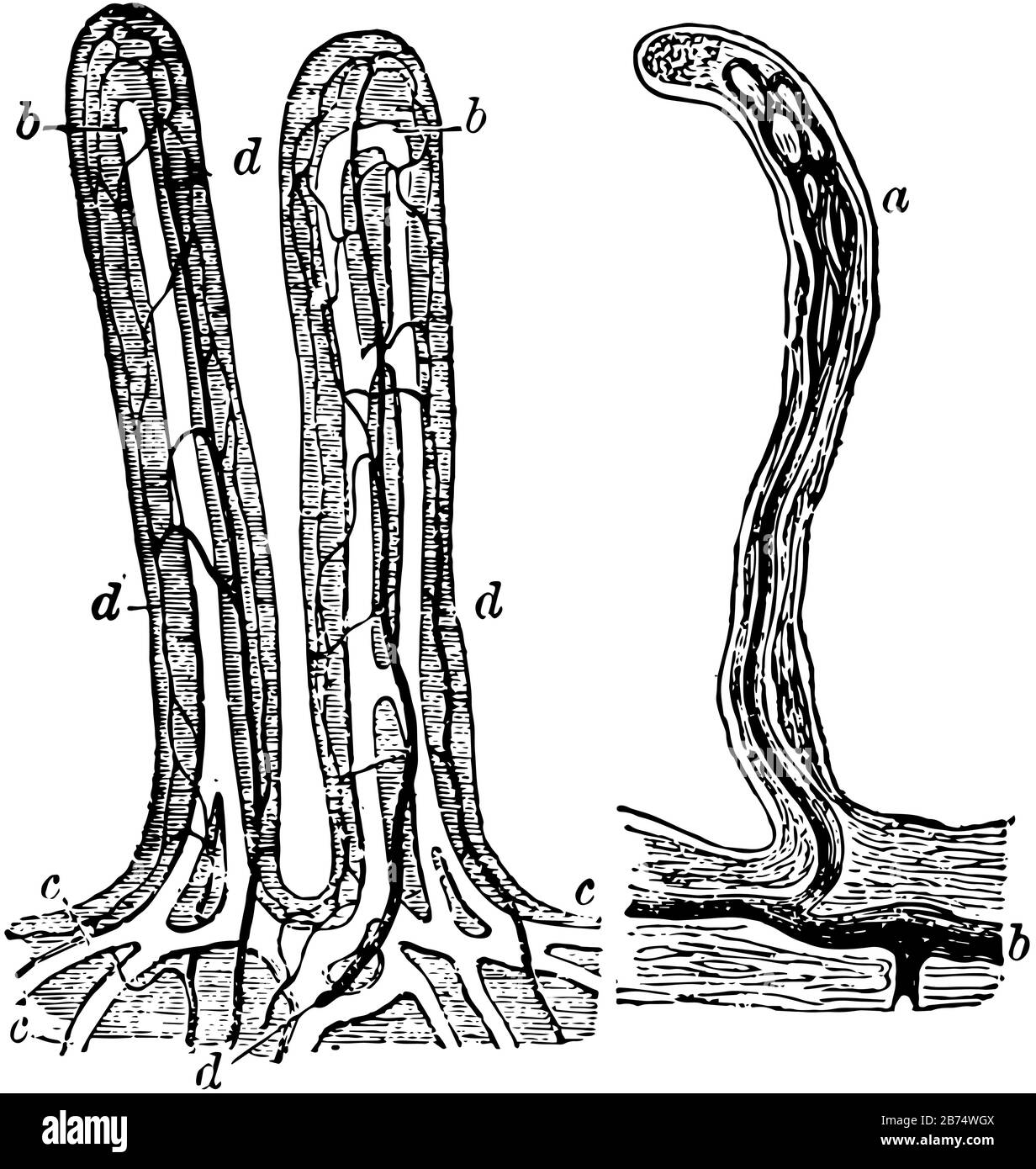

What a Single Villus Actually Looks Like Up Close

A single villus is tiny. We’re talking about 0.5 to 1.6 millimeters in length. They are so small that you can just barely see them with the naked eye if you look at a piece of intestinal tissue under water; they look like a fine fuzz. But don't let the size fool you. Each one is a high-tech processing plant.

The outer layer is the "skin" of the villus, known as the epithelium. This isn't just a static wall. It is made of a single layer of columnar epithelial cells. These cells are the gatekeepers. They decide what gets into your bloodstream and what stays out. Most of these are enterocytes, which are the workhorses of absorption.

Interspersed among them are goblet cells. These are shaped like little wine glasses—hence the name—and their entire job is to pump out mucus. This mucus keeps the "forest" lubricated so food (now called chyme) can slide through without tearing the delicate tissue.

Inside that outer shell, things get even more complex. Each villus has a core of loose connective tissue called the lamina propria. Think of this as the infrastructure. It houses the "plumbing" and the "wiring." You've got a loop of capillary beds (tiny blood vessels) and a single, dead-end lymphatic vessel right in the middle called a lacteal.

The Secret of the Brush Border

If you think the structure of a villus is complicated, wait until you look at the individual cells on its surface. Each of those epithelial cells has its own tiny, hair-like projections called microvilli. This is what scientists call the "brush border."

✨ Don't miss: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s like a fractal. A fold has a villus, and a villus has a microvillus.

The microvilli aren't just for show. They are packed with enzymes like lactase and sucrase. If you’ve ever felt bloated after drinking milk, it’s because the lactase enzymes on your brush border aren't doing their job of breaking down lactose. This microscopic layer is where the final stage of digestion happens. It’s the literal interface between the outside world (your food) and your internal biology.

Why the Blood Supply Matters

Inside the villus, the arrangement of blood vessels is very specific. Arterioles bring oxygenated blood in, and venules carry nutrient-rich blood out. This blood doesn't just go anywhere; it’s funneled straight to the liver via the hepatic portal vein.

The liver acts like a customs office. It checks everything the villi absorbed, filters out toxins, and decides how to distribute the glucose and amino acids to the rest of the body.

But what about fats?

Fats are too big and clunky to fit into the tiny capillaries. This is where the lacteal comes in. That central lymphatic vessel sucks up the fatty acids and carries them through the lymphatic system, eventually dumping them into the bloodstream near the heart. It’s a bypass system that ensures your body can process lipids without clogging the micro-circulatory works.

When the Structure Breaks Down: Celiac and Beyond

You can't talk about the structure of a villus without talking about what happens when it disappears. In people with Celiac disease, an autoimmune reaction to gluten causes the immune system to attack these tiny fingers.

🔗 Read more: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

The villi don't just get "damaged"—they flatten out.

This is called villous atrophy. Imagine a shag carpet being mowed down until it's as flat as a hardwood floor. Suddenly, that tennis-court-sized surface area shrinks to the size of a coffee table. This is why people with untreated Celiac suffer from malnutrition and weight loss. It doesn't matter if they eat a 4,000-calorie diet; they simply don't have the "fingers" left to grab the nutrients as they pass by.

Other things can mess with the structure too.

- Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO): Bacteria can hang out in the "valleys" between villi (called the Crypts of Lieberkühn) and interfere with enzyme production.

- Giardiasis: This parasite literally sits on top of the villi like a suction cup, blocking the absorption of fats.

- Tropical Sprue: A condition that causes the villi to swell and flatten, often seen in specific geographical regions.

The Crypts of Lieberkühn: The Fountain of Youth

Down at the base of the villi are deep pits called the Crypts of Lieberkühn. This is where the magic of regeneration happens. The cells on the tips of your villi are constantly being worn off by the passage of food. In fact, you replace your entire intestinal lining every three to five days.

Deep in these crypts are stem cells. These cells divide rapidly, pushing new cells upward like an escalator. As they move up the villus, they mature and specialize. By the time they reach the tip, they are fully functional enterocytes ready to absorb nutrients. Eventually, they get sloughed off into the gut and are replaced by the next wave. It is one of the fastest-growing tissues in the human body.

Beside the stem cells, the crypts contain Paneth cells. These are the "security guards." They secrete antimicrobial peptides and lysozymes that keep the bacterial population in check. Without them, the bacteria in your gut would quickly overwhelm the delicate epithelial barrier.

Mapping the Surface Area

Let’s look at the sheer scale here.

The human small intestine is roughly 6 to 7 meters long.

The circular folds (plicae circulares) increase the surface area by a factor of 3.

The villi increase it by another factor of 10.

The microvilli increase it by another factor of 20.

💡 You might also like: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

Mathematically, this means your gut has about 600 times more surface area than it would if it were just a flat-walled tube. That’s roughly 250 square meters. It is a biological masterpiece of spatial optimization.

Actionable Steps for Gut Health

Understanding the structure of a villus isn't just for biology exams; it has real-world implications for how you feel every day. If these tiny fingers are inflamed or "clogged" with mucus from poor diet, you won't feel your best.

Prioritize Glutamine

L-glutamine is an amino acid that serves as the primary fuel for those rapidly dividing enterocytes in the villi. Foods like bone broth, grass-fed beef, and cottage cheese provide the raw materials your gut needs to rebuild that lining every few days.

Manage Stress for Blood Flow

Because each villus relies on a delicate loop of capillaries, blood flow is everything. When you are in "fight or flight" mode, your body shunts blood away from the digestive tract to your muscles. Eating while stressed literally starves your villi of the oxygen they need to transport nutrients. Try a few deep breaths before your first bite to flip the switch to "rest and digest."

Fiber: The Gentle Sweep

Insoluble fiber acts like a gentle broom that keeps the "valleys" (the crypts) between the villi clear of debris. Without enough fiber, the mucus can become too thick, and the bacterial balance can shift, leading to the inflammation that flattens the villi over time.

Watch the Alcohol

Ethanol is a direct irritant to the epithelial layer. Heavy drinking can actually cause "micro-tears" at the tips of the villi, leading to what people commonly call "leaky gut" or increased intestinal permeability. Keeping alcohol consumption moderate protects the integrity of that single-cell-thick barrier.

The villus is a bridge. It’s the point where the food you eat officially becomes you. Keeping that bridge in good repair is arguably the most important thing you can do for your long-term energy and health.