You know that feeling when you're just... stuck? Not the kind of stuck where you're waiting for a bus, but the deep, existential kind where the walls of your apartment start feeling like they're leaning in a little too close? That’s exactly what the song Counting Flowers on the Wall captures. It’s a masterpiece of the "I’m fine, totally fine" genre of music. Written by Lew DeWitt and performed by the Statler Brothers in 1965, it managed to turn a nervous breakdown into a catchy, chart-topping hit.

It's a weird song. Let’s be real. It’s got this upbeat, almost bouncy rhythm that makes you want to tap your foot, but if you actually listen to the words, it’s a portrait of a man who has completely checked out of reality. He’s not just bored; he’s losing his mind. And yet, it became a massive crossover success, hitting number four on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart and even cracking the top five on the Billboard Hot 100. It proved that you didn't have to be a traditional "country" fan to appreciate a good song about social isolation and watching Captain Kangaroo.

The Statler Brothers and the Birth of a Counter-Culture Country Hit

When the Statler Brothers first recorded Counting Flowers on the Wall, they weren't exactly the superstars they’d eventually become. They were basically the backing vocal group for Johnny Cash. They were touring with the Man in Black, soaking up that outlaw energy, but they had a sound that was rooted deeply in Southern Gospel harmony. It’s that contrast—the clean, four-part harmony singing about a guy who hasn’t left his house in weeks—that gives the track its bite.

Lew DeWitt, the group's tenor, was the one who penned it. He didn't write it as a joke. He wrote it while he was sitting in a hotel room, feeling the crushing weight of life on the road. The song is essentially a giant "get lost" to an ex or a former friend who keeps checking in out of pity. You can hear the sarcasm dripping off the lyrics. "Don't give me that 'how you been' look," he says. He’s reclaiming his right to be miserable on his own terms.

Interestingly, the Statler Brothers weren't even brothers. They were just four guys from Virginia—DeWitt, Don Reid, Harold Reid, and Phil Balsley—who named themselves after a brand of facial tissues they saw in a hotel room. That kind of mundane, everyday origin story fits the vibe of the song perfectly. They weren't singing about grand tragedies or epic romances. They were singing about the small, suffocating details of a lonely life.

Analyzing the Lyrics: Captain Kangaroo and Solitary Refinement

The lyrics are where the magic happens. Honestly, they’re some of the most relatable lines in pop history.

"I've been kicking tires and lighting fires, setting fires to my bridges..."

That’s a hell of an opening line. It’s someone who has burnt their social life to the ground and is now just wandering around the ashes. But then it gets into the specifics of his "busy" schedule. He’s playing solitaire with a deck of fifty-one cards. He’s smoking cigarettes and watching Captain Kangaroo.

✨ Don't miss: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

For the younger crowd, Captain Kangaroo was a staple of children's television that ran for decades. The image of a grown man sitting in a dark room, mesmerized by a kids' show, is both hilarious and devastatingly sad. It’s a vivid depiction of regression. When the world becomes too much to handle, you go back to what’s safe, even if it’s a guy in a red coat talking to a puppet named Mr. Moose.

The chorus is the kicker:

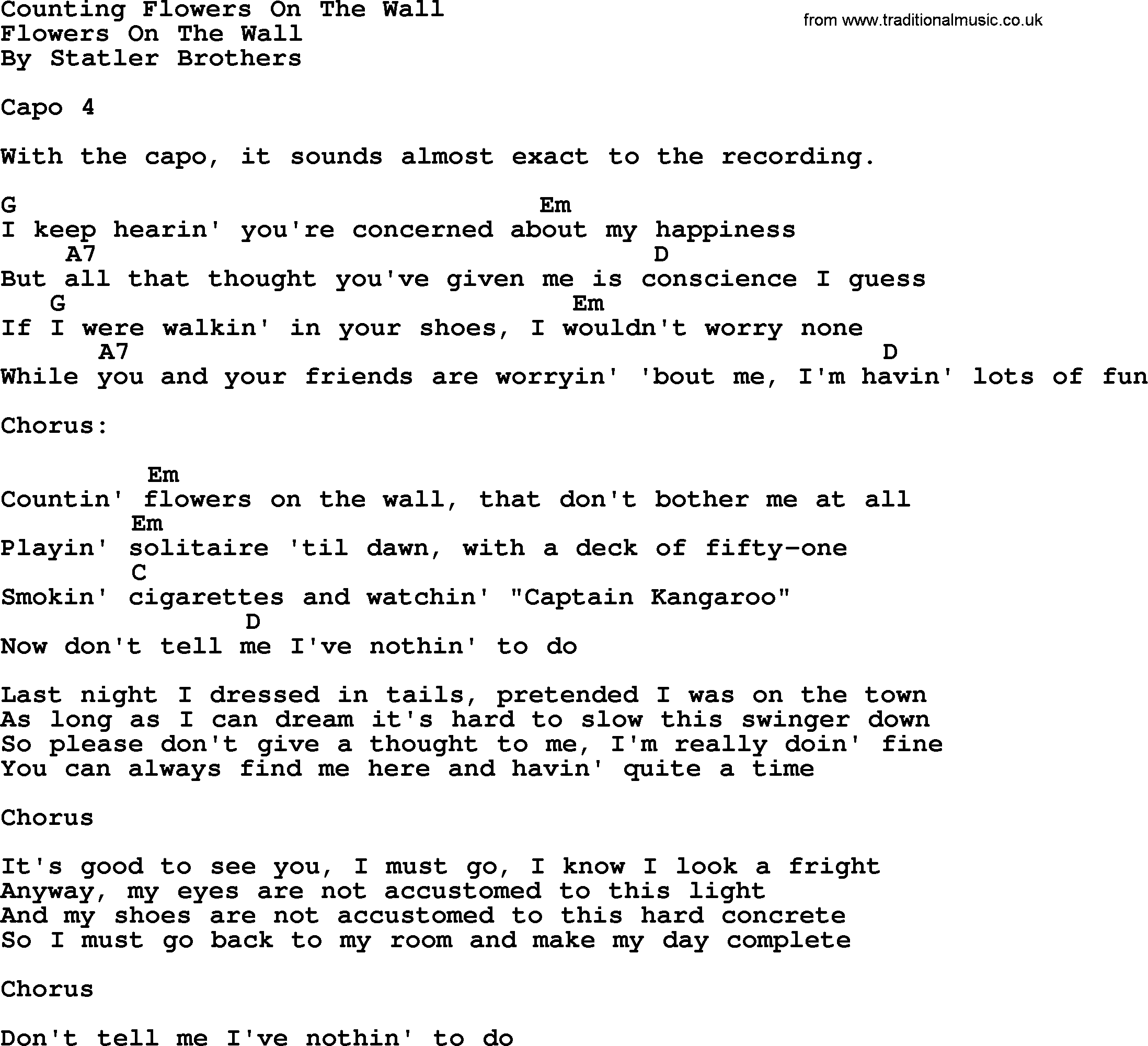

"Counting flowers on the wall, that don't bother me at all. Playing solitaire 'til dawn with a deck of fifty-one. Smoking cigarettes and watching Captain Kangaroo. Now don't tell me I've nothing to do."

He’s defensive. He’s insisting that his meaningless activities are actually a full-time job. It’s a classic defense mechanism. If you convince yourself that you’re "choosing" to be alone, it hurts a little less than admitting you have nowhere else to go.

Why the Song Resonated Across Genres

A big reason Counting Flowers on the Wall worked so well is that it bridged the gap between the Nashville sound and the emerging folk-rock scene of the mid-sixties. While most country songs of the era were about cheating hearts or drinking away sorrows in a bar, this was about the interior life of the mind. It felt modern. It felt like something the Beatles or the Kinks might have written if they grew up in the Shenandoah Valley.

It also didn't hurt that the production was tight. The rhythmic "chug" of the guitar and the bright, soaring harmonies made it radio-friendly. People could sing along to a song about mental stagnation while driving their kids to school. That’s the ultimate irony of the mid-60s pop industry.

The Tarantino Effect: Pulp Fiction and the Second Life

If you ask someone under the age of 50 where they know this song from, they won't say the Statler Brothers. They’ll say Pulp Fiction.

🔗 Read more: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

In 1994, Quentin Tarantino—a guy who treats soundtracks like a lead character—placed the song in one of the film's most iconic scenes. Bruce Willis’s character, Butch, is driving away after reclaiming his father’s gold watch. He’s survived a gauntlet of violence, he’s escaped a certain death, and he’s feeling on top of the world. He starts singing along to Counting Flowers on the Wall on the radio.

He’s literally singing "that don't bother me at all" right before he accidentally runs into Marsellus Wallace, the mob boss he’s trying to hide from.

Tarantino’s use of the song was brilliant because it played with the song's inherent irony. In the song, the narrator is lying to himself about being okay. In the movie, Butch is genuinely happy, but the song foreshadows the fact that his "peace" is about to be shattered. This needle-drop sent the song back into the cultural zeitgeist, introducing a whole new generation to the Statler Brothers' brand of "country-politan" angst.

Impact and Legacy in Country Music

The Statler Brothers went on to have a massive career, winning three Grammy Awards and numerous CMA awards, but they never quite recaptured the lightning-in-a-bottle weirdness of their first big hit. They eventually shifted toward more nostalgic, humorous, and spiritual content, becoming staples of the Hee Haw era.

But Counting Flowers on the Wall remains their definitive statement. It paved the way for "outlier" country hits. It showed that country music could be neurotic. You can see its DNA in the work of artists like Roger Miller, who mastered the art of the quirky, slightly-off-center hit with songs like "King of the Road."

It’s also been covered by everyone from Nancy Sinatra to Eric Heatherly. Heatherly actually took a rockabilly version of the song to the country top ten in 2000, proving the melody and the sentiment are evergreen.

The Realism of Lew DeWitt's Writing

It’s worth noting that Lew DeWitt’s life had its own share of struggle. He suffered from Crohn’s disease, which eventually forced him to retire from the group in the early 80s. When you know that the man who wrote a song about being confined to a room was someone who frequently dealt with chronic illness, the lyrics take on a much heavier weight. It wasn't just a clever metaphor for a breakup; it was about the reality of being stuck when you desperately want to be moving.

💡 You might also like: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

What Most People Get Wrong About the Meaning

People often think this is a "sad" song. I’d argue it’s actually a "spite" song.

The narrator isn't asking for help. He isn't crying. He’s being incredibly smug about his isolation. He’s telling the people from his past that his "boring" life is actually better than whatever fake social drama they’re involved in. There’s a power in that. It’s the ultimate "you can't fire me, I quit" of social relationships.

When he says, "It’s good to see you, I must go," he’s not being polite. He’s ending the conversation because he genuinely prefers the company of his fifty-one cards and the "flowers" (likely the pattern on the wallpaper) over the person standing in front of him. It’s an anthem for the antisocial.

Actionable Insights for Music Lovers and Songwriters

If you’re a fan of the track or a songwriter looking to capture that same energy, there are a few things you can learn from how this song was built.

- Lean into Specificity: The song doesn't just say "I watch TV." It says "I watch Captain Kangaroo." Specificity creates a world. It gives the listener something to latch onto.

- Juxtapose Tone and Content: If you have a dark or depressing lyric, try putting it over an upbeat melody. The tension between the two creates a much more interesting emotional experience than a sad song that sounds sad.

- The Power of the Non-Sequitur: "Kicking tires and lighting fires" doesn't necessarily have a literal meaning in the context of the story, but it sounds right. It captures a restless, destructive energy.

- Respect the "Broken" Element: The "deck of fifty-one cards" is the most important detail in the song. It tells us everything we need to know—that things aren't quite right, and the narrator has stopped caring about fixing them.

Next time you find yourself stuck at home, staring at the walls and feeling like you’ve run out of things to do, put this track on. It won't necessarily make you feel better, but it’ll remind you that people have been "counting flowers on the wall" for over sixty years, and there’s a certain kind of dignity in just leaning into the weirdness of it all.

To dig deeper into the Statler Brothers' discography, look for their 1975 album The Best of the Statler Brothers, which features their most essential vocal harmonies. You can also find Lew DeWitt’s solo work, which carries much of that same dry wit that made their early hits so compelling. For a modern perspective on the "isolation" genre, compare this track to the lyrics of mid-2000s indie rock; you'll be surprised how much they owe to this 1965 country classic.