It’s 1789. Paris is sweating. Not just from the July heat, but from a bone-deep, jittery panic that makes people do crazy things. For weeks, rumors had been rippling through the city like a virus: King Louis XVI was supposedly massing troops outside the city to crush the newly formed National Assembly. People were hungry, the price of bread was astronomical, and honestly, everyone was just fed up with the absolute monarchy. When the King fired Jacques Necker—a finance minister the commoners actually liked—the city finally snapped.

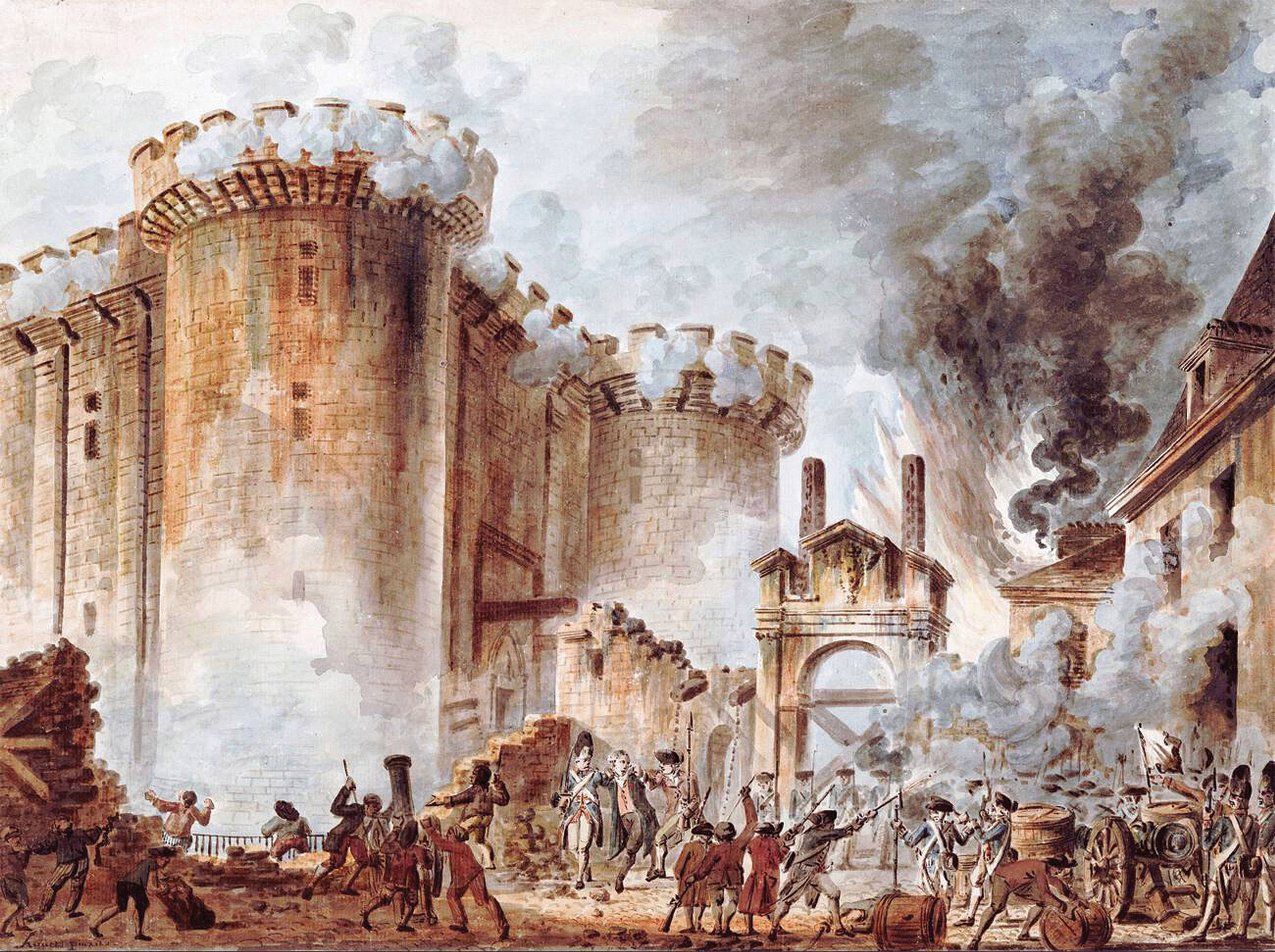

The storming of the Bastille wasn't some grand, pre-planned military operation. It was a chaotic, desperate scramble for gunpowder. You’ve probably seen the paintings of a glorious, coordinated charge, but the reality was much messier, much bloodier, and way more accidental than the history books usually let on.

Most people think the crowd wanted to free a massive hoard of political prisoners. They didn't. They wanted the gunpowder stored inside the fortress’s thick medieval walls to fuel the muskets they’d just stolen from the Hôtel des Invalides. It was about survival and leverage, not just symbolism.

The Myth of the Great Liberation

Let’s be real: the Bastille was kind of a joke as a prison by 1789. It was an aging fortress that the government was already considering tearing down because it was too expensive to maintain. On the morning of July 14, there were exactly seven prisoners inside.

Seven.

Hardly a bastion of mass oppression at that specific moment. Among them were four forgers, two mentally ill men, and one "deviant" aristocrat who had been locked up at his family’s request. The legendary Marquis de Sade had actually been transferred out just days earlier after screaming through a makeshift megaphone that the guards were massacring the prisoners. He lied, but it worked to rile up the neighborhood.

The crowd didn't show up to "break the chains" of thousands. They showed up because they had 30,000 muskets and zero bullets. The Bastille held 250 barrels of gunpowder. That’s the math that changed the world.

👉 See also: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

The governor of the Bastille, Bernard-René de Launay, was in a tough spot. He wasn't a monster; he was a bureaucrat. He actually invited the leaders of the mob in for lunch to talk things over. While they were eating, the crowd outside grew impatient. They thought the negotiators were being held hostage. Some guys climbed onto the roof of a nearby shop, jumped onto the wall, and lowered the drawbridge.

Then, everything went sideways.

Why the Storming of the Bastille Became a Turning Point

When the drawbridge dropped, the crowd rushed in. The soldiers inside—mostly "Invalides," who were veteran soldiers with disabilities—panicked and opened fire. It was a bloodbath. About 100 people died in the chaos.

Eventually, a group of defecting French Guard soldiers arrived with cannons. These weren't amateurs; they were trained military men who had decided they’d rather side with the people than the King. They aimed the cannons at the main gate. De Launay realized his 114 men couldn't win a prolonged siege, especially since they didn't have enough food or water for more than a couple of days. He surrendered.

But surrender didn't mean safety.

The crowd was furious about the 100 people who had been shot. Despite promises of safe passage, De Launay was dragged toward the Hôtel de Ville. He was beaten, stabbed, and eventually killed. His head was put on a pike. This became a gruesome trend of the French Revolution. It was the first time the people of Paris realized that if they acted as a mob, they had more power than the King’s army.

✨ Don't miss: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

The King’s Diary: A Famous Misunderstanding

There is a famous story that Louis XVI wrote "Rien" (Nothing) in his diary for July 14, 1789. People love to point this out as proof that he was out of touch. "The world is ending and he thinks nothing happened!"

That’s a bit unfair.

The diary was primarily a hunting log. "Rien" meant he didn't bag any deer or boars that day. However, it does show that the court at Versailles, which was several miles away, had no clue the city had effectively fallen to a populist insurrection until much later that night. When the Duke of Liancourt told Louis what happened, the King reportedly asked, "Is it a revolt?"

Liancourt replied: "No, Sire, it is a revolution."

The Psychological Impact on Europe

You have to understand how terrifying this was for every other monarch in Europe. The storming of the Bastille was a signal that the old world order was crumbling. If the French—the most powerful and populous nation in Western Europe—could do this, anyone could.

The fortress itself didn't last long. A construction entrepreneur named Pierre-François Palloy started tearing it down almost immediately. He didn't wait for permission. He turned it into a business. He sold "Bastille stones" carved into miniature replicas of the prison. He sent them to every department in France. It was brilliant marketing. He turned a pile of rubble into a permanent symbol of liberty.

🔗 Read more: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

Was it actually a military victory?

Strictly speaking, no. It was a tactical mess. If the King’s commanders at the Champ de Mars had actually ordered their thousands of troops to march into the city, they probably could have retaken the Bastille. But they didn't. They didn't trust their own soldiers to fire on the Parisian people. The military stayed put, and that inaction gave the Revolution the oxygen it needed to survive its first week.

Historians like Simon Schama have pointed out that the violence of that day set a dark precedent. It proved that "the people" could dictate policy through the threat of the pike. This led directly to the more radical phases of the Revolution, like the Reign of Terror.

What You Can Learn from July 14

The storming of the Bastille teaches us that symbols are often more powerful than reality. The prison wasn't a major threat, but it looked like one. Its destruction felt like the destruction of the King’s will.

When you look at this event today, think about the power of the "unintended consequence." The mob didn't set out to start a decade of war and the rise of Napoleon. They just wanted to make sure they could defend themselves against a perceived threat. Small actions, driven by fear and hunger, have a way of cascading into global shifts.

To really grasp the weight of this event, you should look into the "Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen," which was drafted shortly after. It’s the intellectual heart of what began that day.

Practical Next Steps for Further Discovery

- Visit the Site: If you go to Paris today, don't look for the building. It’s gone. Go to the Place de la Bastille and look for the "Colonne de Juillet," but also find the paved outline of the original fortress on the ground near the Metro entrance.

- Primary Sources: Read the letters of Gouverneur Morris, an American in Paris at the time. His eyewitness accounts are far more grounded and cynical than the romanticized versions written decades later.

- Contextual Reading: Pick up The French Revolution: A History by Thomas Carlyle if you want the drama, or Citizens by Simon Schama if you want the gritty, uncomfortable truth about the violence.

- The Necker Connection: Look up why Jacques Necker’s dismissal was the "red flag" for the third estate. It explains why the middle class and the poor finally joined forces.

Understanding the French Revolution isn't just about dates. It's about recognizing when a society’s "social contract" has been shredded so badly that people would rather face cannons than continue living under the old rules.