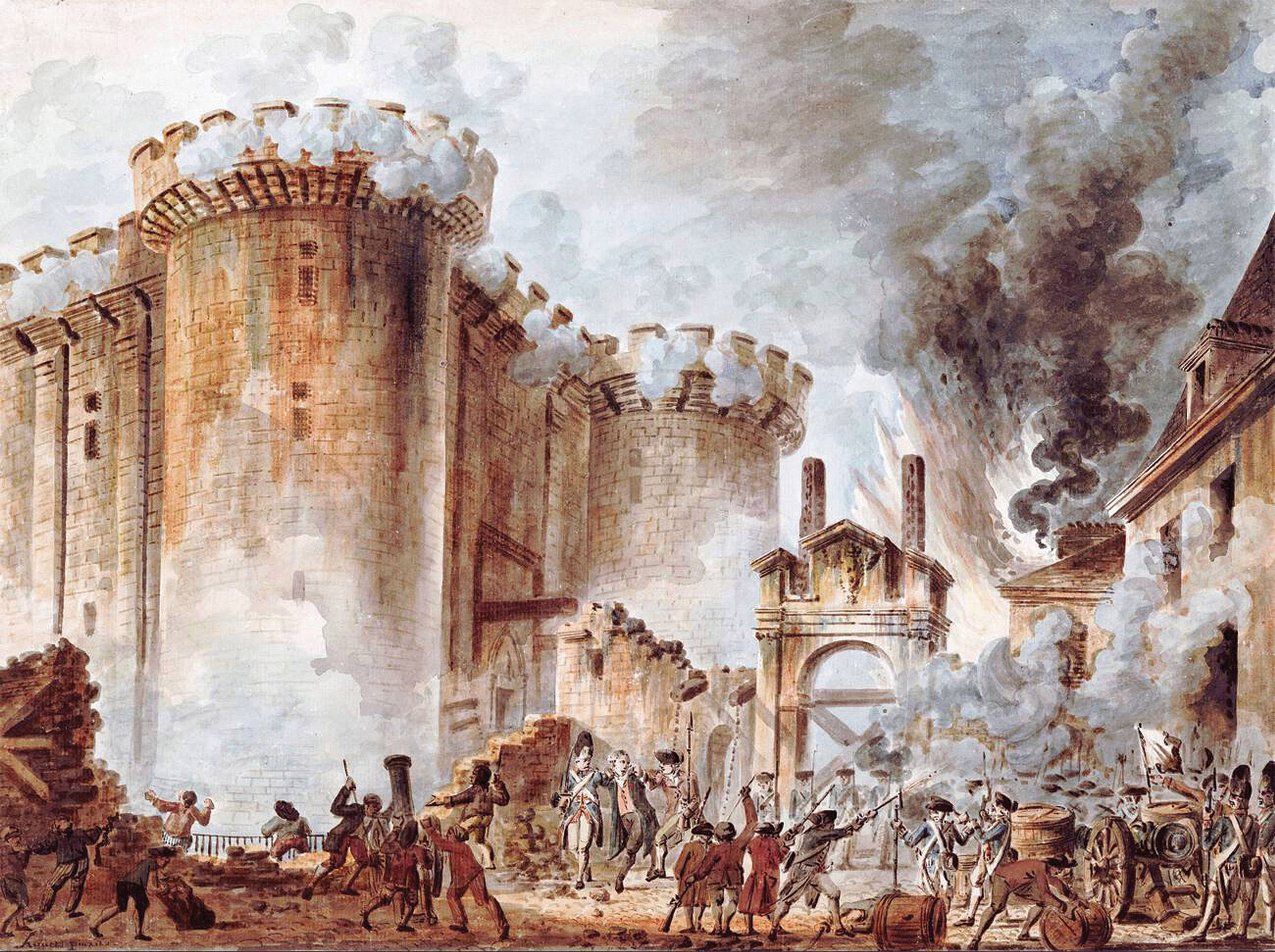

If you close your eyes and think about the Storming of the Bastille, you probably see a massive, heroic charge. Thousands of oppressed peasants swarming a dark, brooding fortress to free hundreds of political prisoners locked away by a tyrant king. It’s a great image. It looks amazing on a postage stamp.

Honestly? It didn’t really happen like that.

History is messy. On July 14, 1789, the Bastille wasn't some overcrowded dungeon. It held exactly seven prisoners. Most were there for pretty mundane reasons, like forging checks or being mentally ill. But the day matters because it was the moment the "Third Estate"—basically the 98% of people who weren't nobles or clergy—realized they had the power to break things. And they did.

Why the Bastille became a target in the first place

Paris in the summer of 1789 was a tinderbox. People were hungry. Bread prices had spiked so high that a loaf cost about a week's wages for a laborer. Think about that next time you complain about grocery bills. King Louis XVI had brought in thousands of foreign mercenary troops to surround the city because he was nervous about the new National Assembly.

The Parisians were terrified. They weren't looking for a fight; they were looking for a way to defend themselves. They had already raided the Hôtel des Invalides earlier that morning and made off with about 30,000 muskets.

One problem. No gunpowder.

The city’s supply of black powder had been moved to the Bastille for safekeeping. That’s the real reason the crowd marched to the fortress. It wasn’t a symbolic crusade against tyranny at first; it was a desperate supply run.

Negotiations gone wrong

The man in charge of the fortress was Bernard-René de Launay. He wasn't some cartoon villain. He was actually a fairly indecisive guy caught in a nightmare. He had about 114 soldiers—mostly Invalides, who were veteran soldiers with disabilities, and a small detachment of Swiss Guards.

👉 See also: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

The crowd gathered around 10:00 AM. They didn't start shooting right away. There were hours of talking. Two representatives went in to have lunch with De Launay. They wanted him to hand over the powder and withdraw the cannons pointing at the Rue Saint-Antoine. He refused to give up the powder but promised not to fire unless he was attacked.

Then things got twitchy.

Around 1:30 PM, a few people managed to climb onto a shop roof and cut the chains to the drawbridge. It crashed down, killing one person in the crowd. The mob rushed into the outer courtyard. The soldiers panicked. Somebody fired a shot. We still don't know who. Then, all hell broke loose.

The myth of the political prisoner

We grew up hearing that the Storming of the Bastille was about liberating the victims of the lettres de cachet—those infamous secret warrants that let the King jail anyone for any reason.

The reality of who was actually inside that day is almost comical:

- Four forgers (Jean La Corrège, Bernard Laroche, Jean Béchade, and Jean-Antoine Pujade).

- Two "lunatics" (one of whom was an Irishman named Tavernier who thought he was Julius Caesar).

- One "deviant" aristocrat, the Comte de Solages, whose family paid to keep him there.

The famous Marquis de Sade had actually been moved to an asylum just ten days earlier because he kept screaming through a funnel that the guards were murdering the prisoners. If he’d stayed, he might have been the "hero" of the day. Instead, the crowd found seven guys who were mostly confused about why a mob was breaking them out.

The moment the tide turned

For most of the afternoon, it was a stalemate. The mob had numbers, but the Bastille had 30-foot walls.

✨ Don't miss: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Then the French Guards (Gardes Françaises) showed up. These were professional soldiers who were supposed to keep order, but they had defected to the side of the people. They brought something the mob didn't have: heavy artillery. They dragged five cannons into position and aimed them at the main gate.

De Launay realized it was over. He threatened to blow up the entire fortress—and the neighborhood with it—by igniting the powder stores. His own men stopped him. They forced him to surrender. He lowered the drawbridge at 5:00 PM, and the crowd surged in.

It ended badly for De Launay. Despite being promised safe passage to the Town Hall, he was beaten, stabbed, and eventually decapitated with a pocket knife. His head was stuck on a pike and paraded through the streets. It was a grisly preview of the Terror that would come a few years later.

Why the King didn't care (at first)

Louis XVI was at Versailles that day. He’d spent the morning hunting. In his diary, for July 14, 1789, he wrote one word: "Rien" (Nothing).

He wasn't saying the revolution was nothing. He was recording that he hadn't caught any prey on his hunt. When the Duke of Liancourt told him about the fall of the Bastille, the King reportedly asked, "Is it a revolt?"

Liancourt’s reply became legendary: "No, Sire, it is a revolution."

The ripple effect: What happened next?

The Storming of the Bastille didn't just end the day it happened. It triggered a total collapse of royal authority. Within weeks, the "Great Fear" spread across the countryside. Peasants started burning the records of their feudal debts.

🔗 Read more: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

- The National Guard: To keep the revolution from turning into total anarchy, the Marquis de Lafayette (yes, the guy from the American Revolution) formed a middle-class militia.

- The Tricolor: They took the red and blue colors of Paris and added the white of the Bourbon monarchy. That’s where the French flag comes from.

- Demolition: A guy named Pierre-François Palloy started a business literally tearing the Bastille down stone by stone. He carved the stones into mini-Bastilles and sold them as souvenirs. He was basically the first guy to sell pieces of a "wall" before the Berlin Wall was even a concept.

Common Misconceptions to Unlearn

We need to stop thinking of this as a "storming" in the sense of a military breach. The people were let in after a surrender.

Also, the Bastille wasn't a huge, functional prison anymore. It was incredibly expensive to maintain, and the government had actually been planning to tear it down and turn it into a public park for years. The revolution just did the job a bit faster and a lot more violently.

How to explore this history today

If you go to Paris today looking for the Bastille, you won't find a castle. You'll find a massive square with a column in the middle (the July Column, which actually commemorates a different revolution in 1830).

But you can still see the ghosts of 1789.

- Place de la Bastille: Look for the paving stones that outline where the towers used to stand.

- Square Henri-Galli: You can see some of the original stone foundations that were moved here during the construction of the Metro.

- Musée Carnavalet: This is the best place to see the actual keys to the Bastille and artifacts from the era.

Actionable Insights for History Lovers

If you want to truly understand the Storming of the Bastille, don't just read the big textbook summaries.

- Read the memoirs of the "Invalides": Their perspective as the guys inside the fort gives a much more human, terrified view of the event.

- Check the bread prices: Research the grain riots of 1788-1789. You can't understand the violence without understanding the starvation.

- Watch the evolution of Bastille Day: See how it changed from a "Federation Festival" in 1790 (meant to celebrate unity) to the military parade it is today.

The Bastille was just a building. But it was a building that represented the King's power to make people disappear. Even if it was nearly empty, pulling it down was the psychological break the French people needed to imagine a world without a King.

The revolution wasn't born in a palace; it was born in a street fight over a pile of gunpowder. That’s the real story. It’s less "clean" than the paintings, but it’s a whole lot more interesting.

Next steps for deeper research:

- Examine the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which was drafted just weeks after the fall.

- Research Jean-Paul Marat and how his journalism fueled the post-Bastille fervor.

- Trace the location of the Bastille Keys—one of them was actually sent by Lafayette to George Washington and is still at Mount Vernon today.