You’re staring at a red or green number on a news ticker. It says the Dow is up 200 points. Most people just nod and think, "Cool, the economy is doing okay today." But if you actually stop to think about it, that’s a weird way to measure reality. The Dow Jones isn't a company. You can't walk into a Dow Jones store and buy a sandwich. It’s just a math problem. Basically, it’s a shortcut.

Understanding a stock market index definition starts with realizing that the market is too big for any human brain to track individually. There are thousands of publicly traded companies. If you tried to check every single one before breakfast, you’d go insane. So, we use indexes as "samples." It’s like taking a tiny sip of a giant pot of soup to see if it needs more salt. You don't need to drink the whole gallon to get the gist.

What a stock market index definition actually looks like in practice

At its simplest, an index is a basket of stocks. But it’s a basket with a specific set of rules. Think of it like a VIP club. To get into the S&P 500, for instance, a company has to meet strict criteria regarding its size, its liquidity, and how long it has been profitable. It’s not just a random list of famous brands.

The "definition" part gets tricky because not every index is calculated the same way. You’ve got price-weighted indexes and market-cap weighted ones. This sounds like boring finance jargon, but it actually changes how your money grows if you’re invested in an index fund. In a price-weighted index like the Dow, a stock with a $200 share price has more influence than a stock with a $50 share price, even if the $50 company is actually ten times bigger in terms of total value. It's a bit of an old-school, clunky way of doing things, but because it’s been around since 1896, we still use it for historical context.

On the flip side, most modern trackers—like the S&P 500 or the Nasdaq Composite—use market capitalization. This means the bigger the company, the more it moves the needle. When Apple or Microsoft has a bad day, the whole index feels the pain. If a tiny company at the bottom of the list goes bankrupt? The index barely flinches.

The heavy hitters you see every day

Most of the time, when people talk about "the market," they are actually referring to one of three things.

💡 You might also like: Business Model Canvas Explained: Why Your Strategic Plan is Probably Too Long

The S&P 500 is the big one. It tracks 500 of the largest companies in the U.S. and covers about 80% of the total available market value. If you want to know how corporate America is doing, this is your best bet. Then you have the Nasdaq, which is heavy on tech and biotech. It’s basically the "future of the economy" index. If people are hyped about AI or chips, the Nasdaq flies. Finally, there's the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which only has 30 companies. It’s meant to represent the "blue chip" backbone of the country—think Coca-Cola, Goldman Sachs, and Disney.

Why does this matter for your actual bank account?

You can't buy an index. You can’t go to a broker and say, "I’d like one Dow Jones, please." Because an index is just a list and a calculation, it’s intangible. However, you can buy an Index Fund or an ETF (Exchange-Traded Fund) that mimics the index.

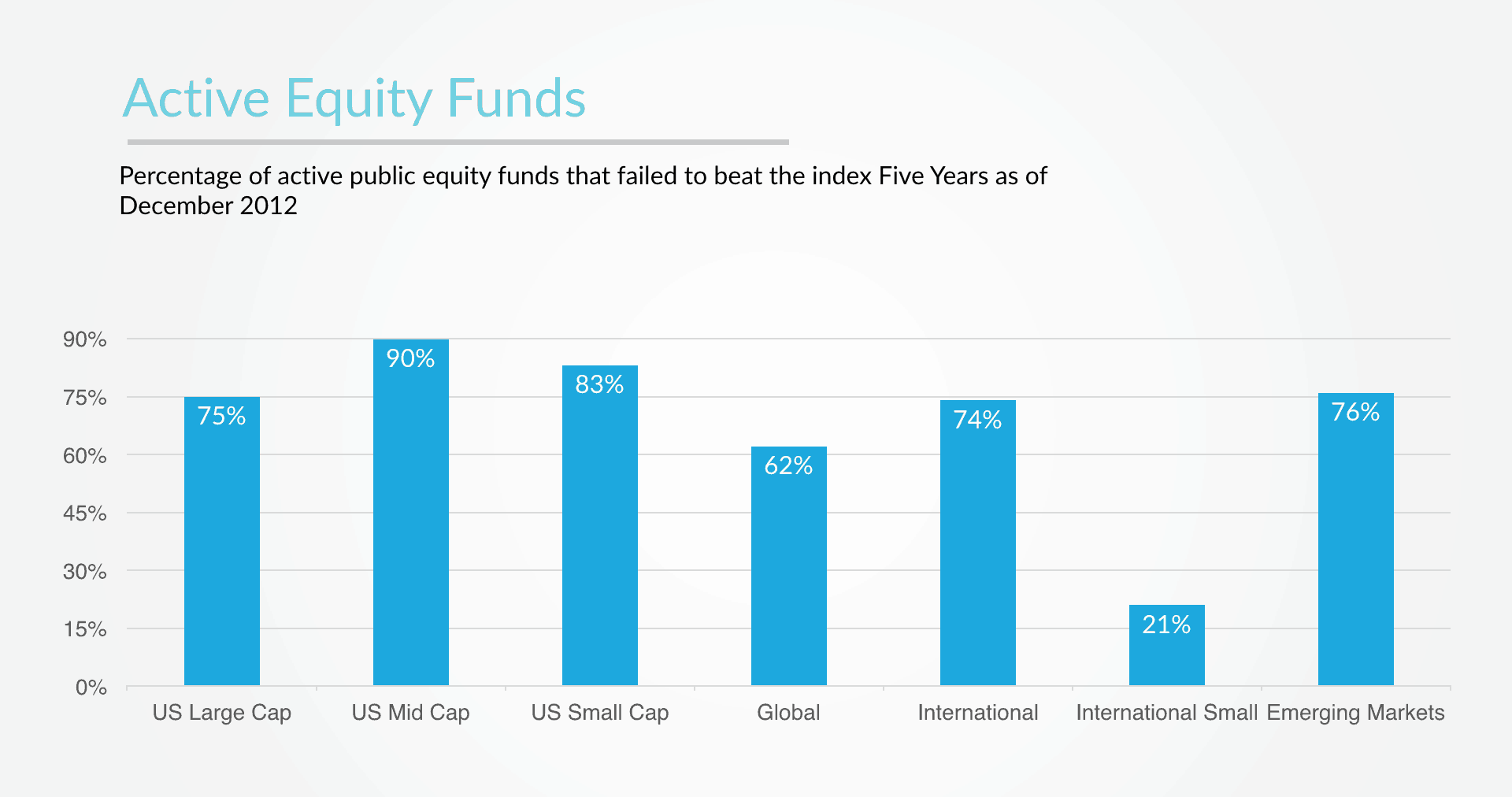

This changed everything for regular people. Before the 1970s, if you wanted a diversified portfolio, you had to buy dozens of individual stocks and pay commissions on every single trade. Then John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, popularized the idea of "passive" investing. He realized that most professional fund managers—the guys in expensive suits on Wall Street—actually failed to beat the S&P 500 over the long run.

So, why pay them a 2% fee to lose to a math formula?

By buying an index fund, you’re basically betting on the entire economy rather than one horse. If the stock market index definition is a "representative sample," then an index fund is a way to own that sample. It’s boring. It’s slow. But historically, it’s been one of the most reliable ways to build wealth.

📖 Related: Why Toys R Us is Actually Making a Massive Comeback Right Now

The dark side of indexing

Everything has a catch. Because so much money is now tied up in these indexes, it creates a "feedback loop." When everyone buys an S&P 500 fund, the fund managers have to buy more of the stocks in that index. This pushes the prices of those specific 500 companies up, regardless of whether they are actually doing a good job.

Some experts, like Michael Burry (the guy from The Big Short), have warned that this might be creating a bubble. If everyone is buying just because "it’s in the index," the link between a company’s actual profit and its stock price gets blurry. It’s something to keep in mind: when you buy an index, you’re buying the winners, but you’re also forced to buy the overvalued companies that happen to be large.

Global benchmarks and specialized niches

It isn't just a U.S. phenomenon. Every major economy has its own version.

- FTSE 100: The top 100 companies on the London Stock Exchange.

- Nikkei 225: The heavyweights in Tokyo.

- DAX: Germany’s 40 biggest players.

- MSCI World: This one is cool because it tracks thousands of stocks across 23 developed countries.

There are also sector indexes. If you think cloud computing is the next big thing, you don’t have to pick between Amazon and Google. You can look at a tech-specific index. Or a green energy index. Or even a "Vice Index" that tracks tobacco, gambling, and alcohol stocks. There is an index for basically every human whim and industrial sector.

A quick word on "Points" vs "Percentages"

One thing that confuses people is hearing "The market dropped 500 points!" That sounds terrifying. But if the index is at 40,000, a 500-point drop is only 1.25%. Back in the 1980s, a 500-point drop would have been a total economic apocalypse. Honestly, you should almost always ignore the points and look at the percentage. The percentage is the only thing that tells you the actual "weight" of the move.

👉 See also: Price of Tesla Stock Today: Why Everyone is Watching January 28

How to use this knowledge right now

If you’re trying to get your head around your own 401k or brokerage account, don't overcomplicate it. Most people get paralyzed trying to pick the "best" stock. You don't have to.

- Check your expense ratios. If you’re in an index fund, you should be paying almost nothing. If your fund is charging you more than 0.20% a year to track the S&P 500, you’re being ripped off.

- Identify your overlap. A lot of people buy an S&P 500 fund and a "Growth Fund" only to realize they own the exact same companies in both. You're not diversified; you're just doubled up on Apple.

- Think about the "Total Market." If the S&P 500 definition feels too narrow (since it's only 500 companies), look into a Total Stock Market Index. These track closer to 3,000 or 4,000 companies, including the small ones that might become the next giants.

The whole point of a stock market index definition is to provide a baseline. It’s the "average." When a hedge fund manager says they "beat the market," they mean they did better than the index. For most of us, just matching the index is more than enough to retire comfortably. It’s the one area of life where being "average" actually makes you a winner over thirty years.

Realize that the index is a living thing. It changes. Companies that fail get kicked out. New, hungry companies get added. It’s a self-cleaning oven. This is why the long-term chart of the major indexes generally goes up and to the right—it’s constantly shedding the losers and adding the winners.

Stop checking the daily fluctuations. It’s noise. Focus on the fact that an index represents the collective productivity and innovation of thousands of people working at the world's largest companies. As long as you believe that humans will keep trying to make money and solve problems, the index is a decent place to be.

Next Steps for Your Portfolio

To put this into action, start by looking at your current investment holdings. Identify which benchmark each of your funds is trying to track. If you find you are heavily weighted in a single sector—like tech—consider adding a "Total International Index" to balance out the US-centric nature of the S&P 500. Finally, verify the rebalancing schedule of your chosen index; most do this quarterly or semi-annually, which is a great time for you to also check in on your personal asset allocation to ensure it still aligns with your long-term goals.