You’ve probably seen that colorful poster in a middle school hallway. It has a nice, neat vertical line of boxes—Observation, Hypothesis, Experiment, Result. It looks so clean. So easy. Honestly? It’s a bit of a lie. Real science is a messy, looping, frustrating, and exhilarating disaster of trial and error. If you’re looking for the steps for scientific method, you need to understand that it isn't a recipe for a cake; it’s more like a compass for a forest where the trails keep moving.

Science doesn't happen in a vacuum. It happens when someone notices that their bread grew weird blue mold or when a data point in a telescope feed doesn't align with where a planet "should" be. This process is the backbone of everything from the smartphone in your pocket to the life-saving vaccines developed in record time. It is a logical framework, sure, but it’s also a deeply human one.

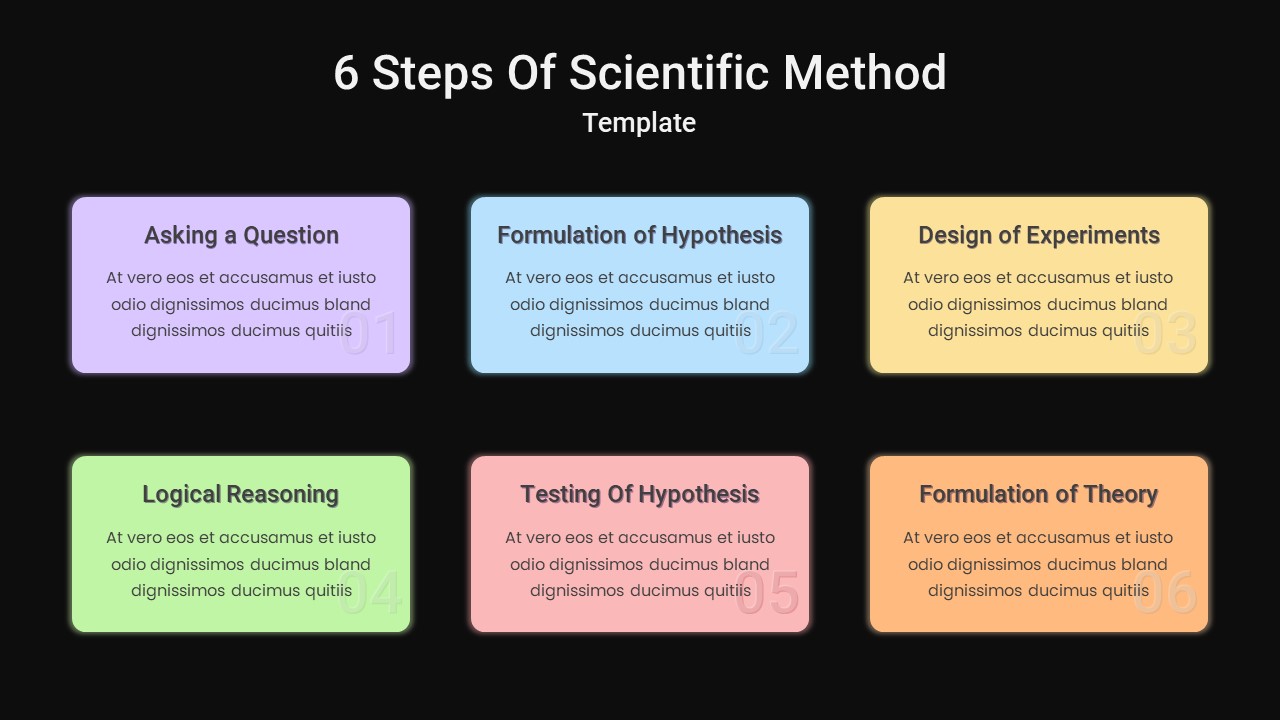

It Starts With a "Huh, That’s Weird" Moment

Everything begins with observation. This is the first of the steps for scientific method, but it’s often the most overlooked. You aren't just looking; you're seeing. Think about Alexander Fleming. He didn't sit down and say, "Today, I shall invent penicillin." He came back from vacation and saw that some staphylococci culture plates had been contaminated by a fungus, and the bacteria around the fungus were dying.

A lot of people would have just thrown the "ruined" plates away. Fleming didn't. He asked why.

That "why" is the bridge to the next phase. You take a raw observation and you sharpen it into a specific question. It can't be vague. "Why is the sky blue?" is a great start, but "Does the color of the sky change based on the concentration of particulate matter in the atmosphere?" is a scientific question. You need something you can actually bite into.

The Hypothesis: Your Best Educated Guess

A hypothesis isn't just a random stab in the dark. It’s a "provisional explanation." You are basically saying, "I bet this happens because of that."

One of the biggest misconceptions about the steps for scientific method is that a hypothesis has to be right. It doesn't. In fact, some of the most important moments in history happened because a hypothesis was spectacularly wrong. A good hypothesis must be falsifiable. This is a term coined by philosopher Karl Popper. If you can't prove it wrong, it isn't science.

💡 You might also like: Why Your Facebook Cover Pic Template Always Looks Blurry (And How to Fix It)

For example, if I say, "Invisible, undetectable ghosts make my car start," that’s not a hypothesis. There’s no way to test it. But if I say, "My car starts because the battery has at least 12.4 volts of charge," we can work with that. We can measure it. We can prove it wrong.

Testing and the Art of the Controlled Experiment

This is where the rubber meets the road. To test your idea, you need an experiment. But you can't just change everything at once. If you're trying to figure out why your sourdough bread didn't rise, and you change the flour, the oven temperature, and the water source all at the same time, you’ve learned nothing.

You need variables.

- The Independent Variable: This is the thing you change. The amount of yeast. The temperature. The dosage of a drug.

- The Dependent Variable: This is what you measure. The height of the bread. The blood pressure of the patient.

- The Control Group: This is the "normal" version. It’s your baseline. Without a control, you have no context.

In the 1950s, when Jonas Salk was testing the polio vaccine, they didn't just give it to everyone. They had a massive "double-blind" study. Some kids got the vaccine; others got a placebo. Neither the kids nor the doctors knew who got what. Why? Because humans are biased. We see what we want to see. This rigor is what makes the steps for scientific method so powerful. It protects us from our own brains.

Data Doesn’t Care About Your Feelings

Once the experiment is running, you collect data. This can be numbers—quantitative—or descriptions—qualitative. Both matter. But here is the kicker: you have to look at the data objectively.

Sometimes the data is "noisy." You might find a correlation that isn't a causation. There’s a famous, somewhat hilarious example showing that ice cream sales and shark attacks both rise at the same time. Does ice cream cause shark attacks? No. They both happen more often in the summer when it’s hot.

Analyzing data often requires math, specifically statistics. You’re looking for "statistical significance." This basically means the odds of your result happening by pure luck are very low—usually less than 5%. If your results aren't significant, you head back to the drawing board. You don't fudge the numbers. You don't ignore the outliers. You accept the reality the data gives you.

The Loop: Why Science Never Really Ends

After you analyze the data, you draw a conclusion. Your hypothesis was either supported or it wasn't. But wait. You aren't done.

Science is a community sport.

You have to share your findings. This usually happens through peer review. This is the gauntlet. You write up your methods, your data, and your results, and you send it to a journal. Then, other experts—people who are often your "rivals"—tear it apart. They look for holes in your logic. They check your math. They try to see if they can replicate your results.

If they can't replicate it, your "discovery" is just a fluke. This happened with the famous "cold fusion" announcement in 1989. Two researchers claimed they’d figured out how to create nuclear energy at room temperature. The world went nuts. But when other scientists followed the steps for scientific method to try and recreate the experiment, they failed. The original result wasn't a breakthrough; it was an error.

Real-World Nuance: It's Not Always a Lab

We often think of scientists in white coats, but these steps apply everywhere.

- In Business: A startup thinks a new feature will increase user retention (Hypothesis). They roll it out to 10% of users (Experiment). They check the metrics (Data). They decide whether to keep it (Conclusion).

- In Medicine: Doctors notice a cluster of symptoms (Observation). They suspect a specific virus (Hypothesis). They run blood tests (Experiment). They treat based on those results.

- In Daily Life: Your WiFi is out. You think it's the router (Hypothesis). You unplug it and plug it back in (Experiment). It works (Conclusion). You just used the scientific method to fix your Netflix stream.

Common Pitfalls and Misconceptions

One major issue is Confirmation Bias. We naturally look for evidence that proves we are right and ignore evidence that proves we are wrong. The scientific method is specifically designed to fight this instinct.

Another is the confusion between a Theory and a Law. In common speech, "theory" means a guess. In science, a Theory (like Germ Theory or the Theory of Evolution) is a massive framework that has been tested thousands of times and has never been proven wrong. A Law (like the Law of Gravity) describes what happens, while a Theory explains why it happens. Both are incredibly robust.

How to Apply This Right Now

If you want to think more scientifically, start with your own assumptions. Pick something you "know" to be true about your productivity, your health, or your hobbies.

First, define it clearly. "I work better in the morning."

Second, track it. For one week, do your hardest task at 8:00 AM. The next week, do it at 4:00 PM.

Third, look at the output. Did you actually get more done, or did you just feel more productive?

The data might surprise you.

🔗 Read more: Who Made the First Ever Car: Why Most People Get the Answer Wrong

The beauty of the steps for scientific method is that they don't require a PhD. They just require curiosity and the courage to be wrong. When we stop guessing and start testing, we stop being victims of our own biases and start becoming architects of our own understanding.

Check your sources. Question the "obvious" answers. Test your own limits. That is how progress actually happens. It's not about being the smartest person in the room; it's about being the person most willing to let the evidence lead the way.

Actionable Takeaways for Scientific Thinking

- Question Your Observations: Ask if what you’re seeing is a pattern or a one-time fluke.

- Isolate Variables: If you're trying to improve a process, change only one thing at a time so you know what caused the shift.

- Seek Disproof: Instead of trying to prove yourself right, try to find ways you might be wrong. It’s a much faster way to find the truth.

- Document Everything: Memory is a liar. Write down your starting point, your actions, and your results to avoid "remembering" things more favorably than they actually happened.