When Francisco Franco finally died in his bed in 1975, most of Spain held its breath. People were terrified. You had a country that had been frozen in a nationalist, Catholic-authoritarian ice box for nearly forty years, and suddenly, the plug was pulled. Everyone expected another civil war. Instead, they got what historians now call "The Spanish transition to democracy," a period so weirdly successful and simultaneously frustrating that political scientists still use it as a textbook case for how to flip a dictatorship without burning the whole house down.

It wasn't a clean break. Honestly, it was a mess of backroom deals and terrifying close calls.

If you go to Madrid today, you’ll see a modern, vibrant European capital. But the ghosts of the Transición are everywhere. You can see them in the way people argue about the "Pact of Forgetting" or the "Law of Memory." It wasn't just about switching from a dictator to a king and a parliament. It was a high-stakes gamble involving a young King Juan Carlos I, a slick politician named Adolfo Suárez, and a whole lot of communist and socialist leaders who decided to play nice for the sake of the country.

They were basically winging it.

The Myth of the Smooth Handover

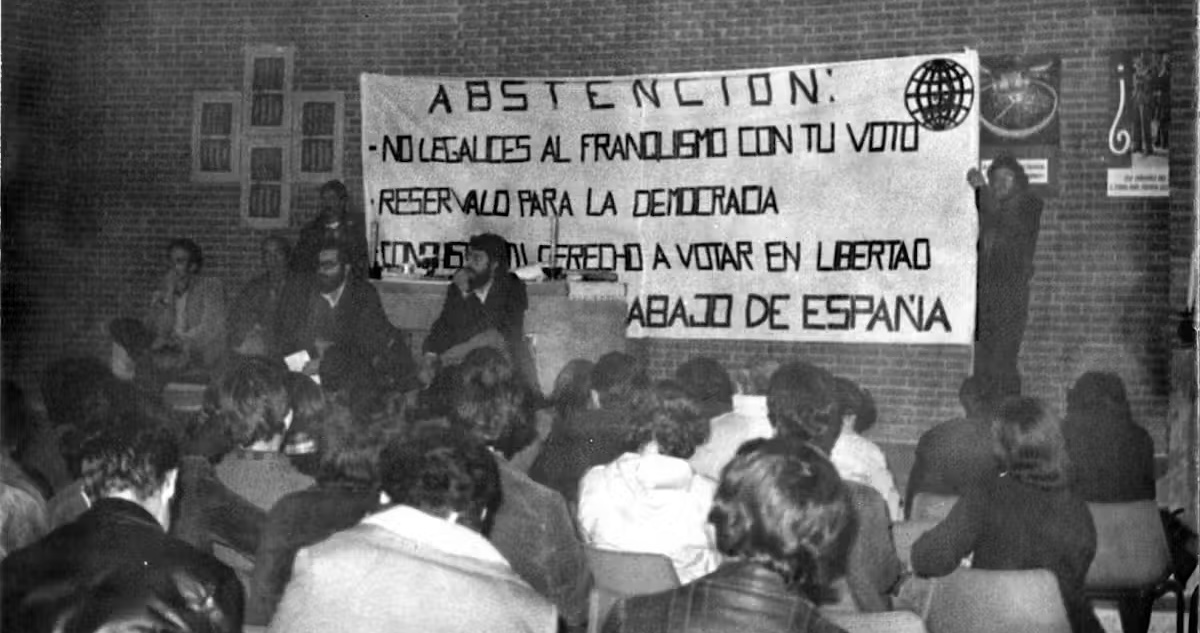

We usually hear that the Spanish transition to democracy was this elegant, peaceful handoff. That’s a lie. Well, a half-truth. It was actually incredibly violent. Between 1975 and 1982, hundreds of people died in political violence. You had the ETA (Basque separatists) blowing up cars, far-right death squads like the Guerrilleros de Cristo Rey attacking leftist bookstores, and police who still used the brutal tactics of the old regime.

People forget the 1977 Massacre of Atocha. Far-right gunmen walked into a labor lawyer's office and just started shooting. Five people died. That was the moment things could have easily spiraled into a second civil war. But something strange happened. Instead of rioting, the Communist Party—which was still technically illegal at the time—organized a massive, silent funeral. Thousands of people lined the streets in total silence. It was a flex. It showed the government that the left was disciplined and ready for democracy, not chaos.

👉 See also: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

Adolfo Suárez: The Man Nobody Expected

Adolfo Suárez was a bit of a "suit." He was a product of the Francoist system, a guy who had climbed the ranks of the Movimiento Nacional. When the King picked him to lead the reform, the liberals were horrified. They thought he was a puppet. But Suárez had this weird, intuitive sense of how to dismantle a system from the inside.

He didn't just tear down the old laws; he used the old laws to commit "legal suicide" for the dictatorship. He convinced the Francoist parliament to vote themselves out of existence. Imagine asking a group of powerful people to fire themselves for the good of the country. He pulled it off.

The Pact of Forgetting: A Necessary Evil?

This is where the Spanish transition to democracy gets controversial. In 1977, the government passed the Amnesty Law. Basically, it said: "Everything that happened during the Civil War and the dictatorship is wiped clean." No trials for torturers. No digging up mass graves. No revenge.

For a long time, the world praised this. They called it the "Pact of Forgetting" (Pacto del Olvido). It allowed Spain to move forward without the weight of 500,000 ghosts dragging them back into the 1930s. But today? Many Spaniards are angry about it. They feel like the victims were never given justice while the perpetrators lived out their lives on fat state pensions.

You see this tension in the work of historians like Paul Preston or Santos Juliá. They’ve spent decades debating whether you can truly have a democracy built on a foundation of silence. Spain is currently still dealing with this. The 2007 Law of Historical Memory and the more recent 2022 Democratic Memory Law are essentially attempts to fix the "holes" left by the original transition.

✨ Don't miss: When is the Next Hurricane Coming 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

That One Night in February 1981

If you want to understand the fragility of this era, you have to look at 23-F. On February 23, 1981, a guy named Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Tejero walked into the Congress of Deputies with a pistol and a tri-cornered hat. He held the entire government hostage on live TV.

It was a coup. Pure and simple.

The military was tired of the "liberal chaos." They wanted the old days back. For several hours, nobody knew if the tanks in Valencia were going to roll into Madrid. The whole thing collapsed because King Juan Carlos I went on television in his full military uniform and told the army to go home. He staked his entire crown on democracy. It was the moment the Spanish transition to democracy became "real" for a lot of people. It survived the ultimate stress test.

What People Get Wrong About the Monarchy

Many people think the King was a democrat by nature. It's more complicated. Juan Carlos was hand-picked by Franco. He was raised to be the dictator's successor. But he realized—quite pragmatically—that a monarchy wouldn't survive in modern Europe if it stayed tied to a dead fascist.

His role in the Spanish transition to democracy was essentially that of a bridge. He kept the military loyal while Suárez worked on the politics. It worked for about forty years. Recently, his reputation has taken a massive hit due to financial scandals and his eventual abdication, but you can't erase the fact that in 1981, he was the only thing standing between Spain and another decade of military rule.

🔗 Read more: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

The Economic Side of the Story

Democracy didn't just happen because people liked freedom. It happened because Spain was broke. By the 1970s, the autarky (self-sufficiency) model was failing. Spain wanted to join the EEC (the precursor to the EU). They wanted to be part of the modern world.

The "Spanish Miracle" of the 60s had created a middle class that wanted to travel, buy cars, and speak their minds. You can't have a 19th-century political system running a 20th-century economy. The pressure from the business elite was just as strong as the pressure from the students in the streets.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you’re trying to wrap your head around how Spain actually works today, you have to look at the scars of this period. It isn't just "history"—it’s the nightly news.

- Visit the sites of memory: If you go to Madrid, visit the Prisión de Carabanchel site or the Reina Sofía Museum. The art of the transition (especially the "Movida Madrileña" movement) tells the story better than any textbook.

- Check the nuance in the 1978 Constitution: Read up on Title VIII. It's the part that gave autonomy to regions like Catalonia and the Basque Country. Most of Spain’s current political drama stems from the vague way this was written to satisfy both centralists and separatists in 1978.

- Follow the "Memory" debates: Look up the work of organizations like the Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica. They are the ones currently digging up the graves that the transition tried to hide.

- Understand the "Two Spains": The transition didn't end the divide between "Red" and "Blue" Spain; it just put it on ice. When you see Spaniards arguing about the Civil War today, they aren't arguing about 1936. They are arguing about whether the 1975-1978 deal was fair.

The Spanish transition to democracy proved that you can negotiate your way out of a dictatorship. It showed that enemies can sit at a table and agree not to kill each other. But it also showed that if you don't deal with the trauma of the past, it eventually catches up to you.

To really understand the current political climate in Spain, start by looking at the 1977 Amnesty Law. It is the single most important document for understanding why Spain looks the way it does today. Read the original text, then look at the 2022 Democratic Memory Law to see how the country is trying to rewrite its own ending.