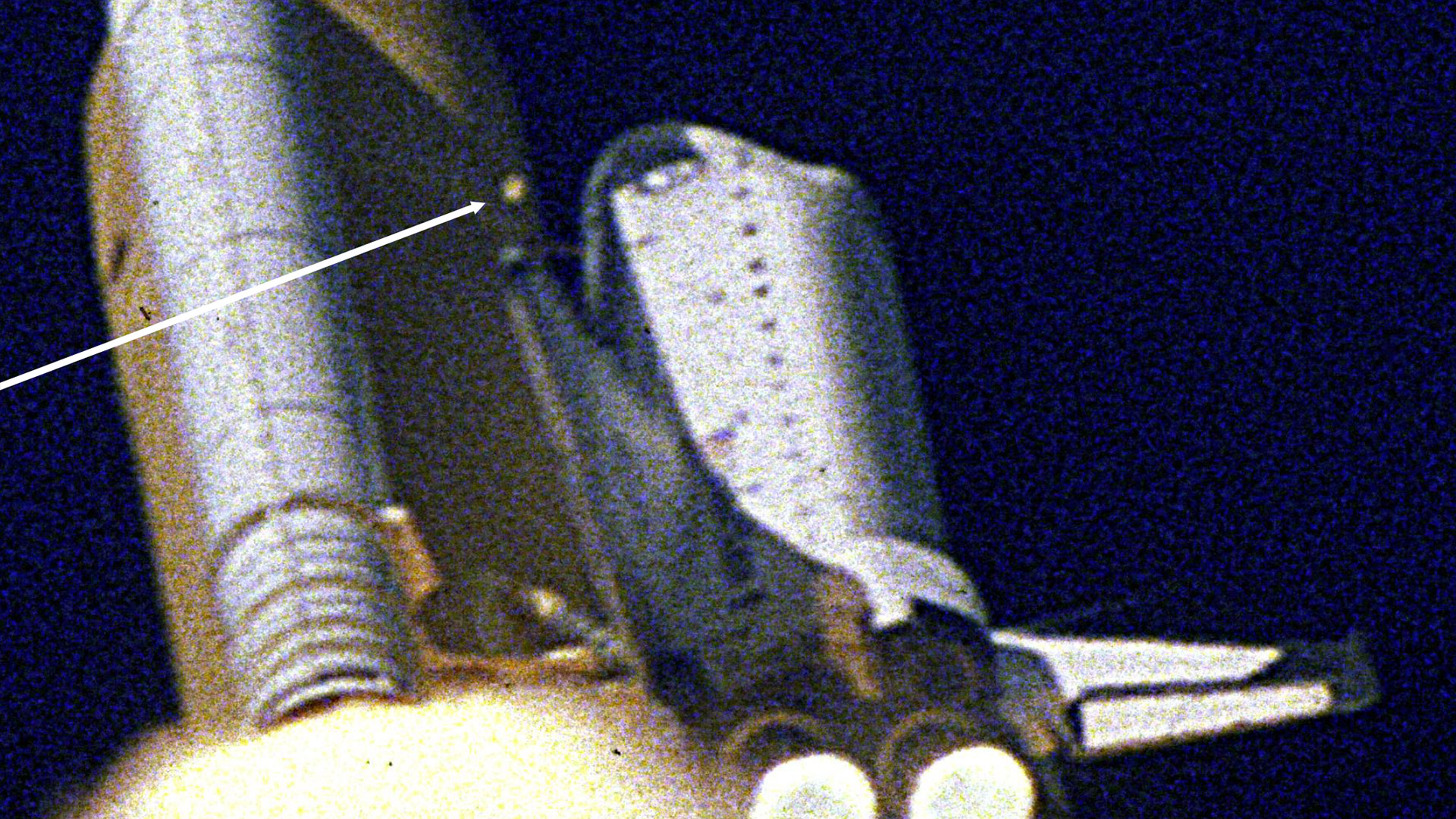

On a chilly January morning in 2003, seven people climbed into a vehicle that was basically a massive, flying brick strapped to a bomb. That sounds dramatic, but it’s the reality of spaceflight. We often forget how precarious it is. When STS-107 lifted off from Kennedy Space Center, it looked like a textbook launch. Smooth. Clean. Routine. Except, eighty-two seconds into the ascent, a chunk of insulating foam—about the size of a briefcase—broke off the external fuel tank. It struck the leading edge of the left wing.

Nobody died then. The mission continued for sixteen days.

The space shuttle Columbia final flight wasn't doomed by a lack of technology. It was doomed by a culture that had grown used to "debris events." NASA engineers saw the strike on video. They debated it. Some were deeply worried. Others pointed to the fact that foam had fallen off before without causing a catastrophe. This is what experts call the "normalization of deviance." It’s a fancy way of saying that if you break a safety rule and nothing bad happens, you start thinking the rule isn't necessary.

Why the Wing Didn’t Stand a Chance

People think the foam was like a piece of Styrofoam hitting a car. It wasn't. Because the shuttle was traveling at incredible speeds, that foam hit the wing at a relative velocity of several hundred miles per hour.

🔗 Read more: hubble telescope how does it work: What Most People Get Wrong

The leading edge of the wing was made of Reinforced Carbon-Carbon (RCC). It’s tough stuff. It has to handle temperatures over $1600°C$ during reentry. But it’s also brittle. The impact punched a hole roughly 6 to 10 inches wide.

Imagine driving a car with a hole in the radiator. You might make it a few miles, but eventually, the heat is going to liquefy the engine. For the crew of Columbia, the "engine" was the entire airframe.

During the sixteen days in orbit, the crew—Rick Husband, Willie McCool, Michael Anderson, Kalpana Chawla, David Brown, Laurel Clark, and Ilan Ramon—performed dozens of experiments. They were studying everything from fire suppression in microgravity to the physiology of silkworms. They were scientists doing science. They had no idea that a hole in their wing was waiting to swallow them whole the moment they touched the atmosphere.

The Warning Signs Ignored

Inside NASA, there were frantic requests for satellite imagery. Engineers wanted the Department of Defense to point their high-resolution cameras at Columbia to see if the wing was damaged.

The request was shut down.

Management felt that even if there was damage, there was nothing they could do. This is a point of huge contention among space historians. Could they have sent Atlantis to rescue them? Maybe. It would have been a "hail Mary" play—launching a second shuttle in record time, bringing the crews together in a dangerous EVA (extravehicular activity). Could the crew have patched the hole with ice and spare parts? Probably not.

But the tragedy isn't just that they couldn't fix it. It's that the hierarchy didn't want to know for sure. They chose "hope" as a strategy.

February 1, 2003: The Breakup

Reentry is a brutal process. You're basically using the Earth's atmosphere as a giant brake pad. As Columbia hit the "entry interface" over the Pacific Ocean, superheated plasma began to sneak into that hole in the left wing.

It acted like a blowtorch.

Slowly, the internal structure of the wing began to melt. Sensors started failing. One by one, the "tire pressure" and "hydraulic temperature" readings on the left side dropped out. In the cockpit, the crew saw the flight control system trying to compensate for a massive drag on the left wing. The shuttle was fighting to stay straight.

It lost.

Over Texas, the wing finally gave way. The orbiter began to tumble. At Mach 18, the aerodynamic forces are so violent that no man-made structure can survive a sideways spin. The space shuttle Columbia final flight ended in a rain of debris across thousands of square miles.

I remember the footage. Those white streaks across the blue morning sky. People on the ground thought they were seeing meteorites. It took a while for the sickening reality to sink in: that was the ship. Those were the people.

The Aftermath and the "Real" Cause

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) didn't just blame the foam. They blamed the "organizational causes." Admiral Hal Gehman, who led the investigation, was blunt. He noted that NASA's safety culture had become "silent."

- The schedule was too tight.

- The budget was squeezed.

- Success was assumed rather than proven.

This is a lesson that applies to more than just rockets. It applies to software engineering, medicine, and bridge building. When we stop being paranoid about what can go wrong, things go wrong.

One of the most haunting pieces of evidence recovered was a flight data recorder that survived the crash. It showed that the crew likely had about a minute of awareness after the breakup began before they lost consciousness due to depressurization. They were working the controls until the very end.

📖 Related: The Name for the At Symbol: What Most People Get Wrong

What We Learned (And What We Didn't)

After Columbia, the shuttle fleet was grounded for over two years. When they returned to flight, every single mission included a "backflip" maneuver. The shuttle would flip over near the International Space Station so the station crew could take high-res photos of the belly tiles.

We stopped pretending foam didn't matter.

However, we also decided to retire the shuttle. The space shuttle Columbia final flight was the beginning of the end for the program. It proved the orbiter was too fragile, too expensive, and too complex for "routine" space travel. It was a sports car when we needed a pickup truck.

Today, we use capsules like the SpaceX Dragon or the Boeing Starliner. They sit on top of the rocket, not on the side. This simple design change means that if foam or ice falls off the tank, it hits nothing. It just falls into the void. We went back to basics because the basics are safer.

The Human Element: Ilan Ramon and the Torah

There are so many small, heartbreaking stories from this flight. Ilan Ramon was the first Israeli astronaut. He carried a tiny Torah scroll that had survived the Holocaust. He carried a drawing by a boy who died at Auschwitz.

Ramon wasn't just a pilot; he was a symbol of resilience. His death, along with the others, felt like a blow to the idea of global scientific unity.

We often talk about the "cost" of space exploration in dollars. But the real cost is measured in the empty chairs at Thanksgiving dinners. Laurel Clark’s husband and son, Kalpana Chawla’s family—they lived the reality of that cost.

Actionable Insights for the Future

If you're a student of history or just someone fascinated by the space shuttle Columbia final flight, there are ways to keep this legacy alive and apply its lessons to your own life or career.

- Study the CAIB Report: It is genuinely one of the most well-written documents on organizational failure ever produced. If you lead a team, read the "Organizational Causes" chapter. It’ll change how you think about "minor" mistakes.

- Visit the Memorials: The "Forever Remembered" exhibit at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex is incredibly moving. It features a piece of the RCC wing from Columbia. Seeing the physical evidence of the damage brings the reality of the physics home in a way no article can.

- Practice Red-Teaming: In your own projects, designate someone to be the "foam skeptic." Their job is to find the one small thing that could snowball into a disaster. Don't let your "standard operating procedure" blind you to new risks.

- Support Crew Safety Initiatives: Spaceflight is entering a new golden age with private companies. Stay informed about safety standards. Pressure for fast launches shouldn't override the lessons we learned in 2003.

The legacy of Columbia isn't just the tragedy. It’s the shift in how we approach risk. We learned that "it worked last time" is the most dangerous sentence in the English language.

The seven who flew on STS-107 knew the risks. They accepted them for the sake of knowledge. The best way to honor them is to make sure we never let "good enough" be the standard again when lives are on the line. Space is hard. It’s unforgiving. But it’s where we belong—as long as we remember the cost of getting there.