October 4, 1957, changed everything. A small, polished metal ball with four whip antennas hissed a rhythmic "beep-beep-beep" as it streaked across the night sky. That was Sputnik 1. It wasn't just a satellite; it was a psychological gut-punch to the West. For a few years there, it really looked like the Soviet Union space race efforts were going to leave the United States in the cosmic dust. People forget how terrifyingly ahead they were.

Honestly, the Soviet lead wasn't just a fluke of good timing. It was the result of a singular, obsessive focus driven by Sergei Korolev. You probably haven't heard his name as much as von Braun’s, mostly because the USSR kept his identity a state secret until he died. They just called him "The Chief Designer." If you lived in 1960, you’d have every reason to believe the first person on the moon would be speaking Russian.

The Soviet Union space race was never really about exploring the stars for the sake of "mankind." Let’s be real. it was about ICBMs. If you can put a dog in orbit, you can put a nuclear warhead on Washington. That’s the subtext that defined every single launch from the Baikonur Cosmodrome.

How the USSR Actually Won the Early Rounds

The sheer volume of Soviet "firsts" is staggering when you look at the raw data. Everyone knows Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space, who circled the Earth in Vostok 1 on April 12, 1961. But the list goes way deeper than that. They had the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, in 1963. They performed the first spacewalk with Alexei Leonov in 1965—a mission that almost ended in disaster when his suit puffed up like a balloon and he couldn't fit back into the airlock. He had to manually bleed his suit's oxygen just to squeeze inside. Talk about nerves of steel.

Success came from a "good enough" engineering philosophy. While NASA was obsessed with perfect, reusable components and hyper-complex electronics, the Soviets built rugged, simple systems. They used "brute force" rocket clusters. The R-7 Semyorka, the rocket that launched Sputnik, is basically the grandfather of the Soyuz rockets that still fly today. It’s reliable. It’s tough. It works in a blizzard.

The Soviets were also the first to hit the moon. Not with people, obviously, but with Luna 2 in 1959. They were the first to take a photo of the far side of the moon. They even managed to land a probe on Venus—Venera 7—which survived for 23 minutes in a literal hellscape of lead-melting heat and crushing pressure. Twenty-three minutes doesn't sound like much, but on Venus, it’s an eternity.

The Secret Cost of Haste

Behind the propaganda posters and the parades in Red Square, things were messy. Really messy. Because the Soviet Union space race was tied so tightly to political anniversaries, engineers were often forced to cut corners to meet deadlines set by the Kremlin.

Take Soyuz 1. Vladimir Komarov knew the ship was a death trap. Engineers found over 200 structural problems before launch, but nobody wanted to be the guy who told Leonid Brezhnev that the 50th anniversary of the Revolution wouldn't have a space spectacular. The parachute failed on re-entry. Komarov became the first human fatality during a spaceflight.

The N1 Rocket: Where the Dream Died

If you want to know why there isn’t a hammer and sickle on the moon right now, look at the N1 rocket. It was the Soviet answer to the Saturn V. It was a beast. Standing 105 meters tall, it had 30 engines at its base. Thirty!

✨ Don't miss: When Was the First iPod Released? The Day Apple Changed Everything

That was the problem.

Plumbing 30 engines to work in sync without vibrating the entire rocket to pieces is an engineering nightmare. The Soviets lacked the advanced computer modeling the Americans were starting to use. They also lacked the funding. While NASA was getting about 4% of the US federal budget at its peak, the Soviet space program was fragmented, underfunded, and plagued by infighting between different design bureaus.

The N1 failed four times. On its second test flight in 1969, it fell back onto the launchpad and created one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in human history. It literally leveled the launch complex. While Neil Armstrong was taking his "small step" in July 1969, the Soviet lunar program was literally smoldering in the dirt of Kazakhstan.

Why Their Strategy Eventually Faltered

- Bureaucratic Infighting: Unlike NASA, which was a centralized civilian agency, the Soviet program was split between rival designers like Korolev, Chelomei, and Glushko. They hated each other. They competed for resources like kids fighting over toys.

- The Death of Korolev: In 1966, Sergei Korolev died during a routine surgery. He was the glue holding the whole thing together. Without his political sway and vision, the program lost its momentum.

- Computer Lag: By the late 60s, the "brute force" approach reached its limit. Spaceflight required microelectronics, and the Soviet Union was lagging behind the Silicon Valley revolution.

The Pivot to Space Stations

The Soviets weren't stupid. Once they realized they lost the moon, they changed the game. If they couldn't reach the moon, they’d own Earth orbit. This led to the Salyut program and eventually Mir.

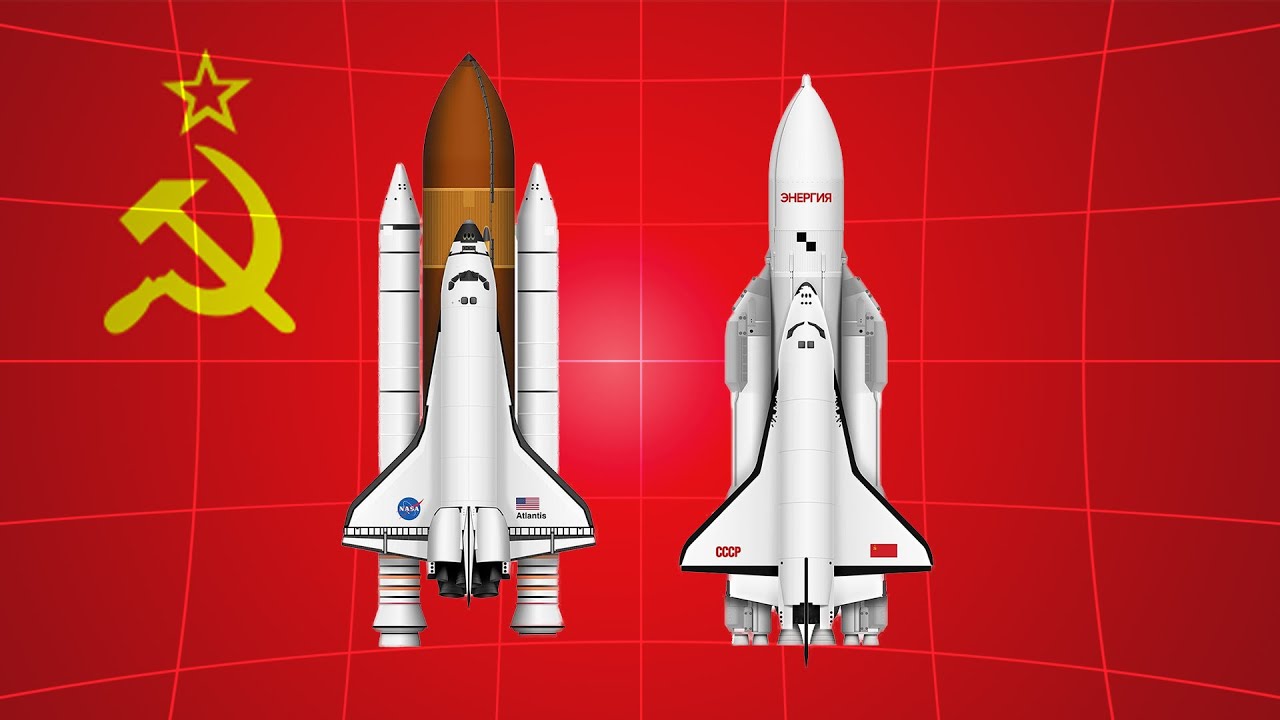

While the US moved on to the Space Shuttle—a brilliant but incredibly expensive and somewhat flawed vehicle—the Soviets mastered long-term human survival in space. They learned how to grow food in orbit, how the human body decays over a year in microgravity, and how to dock modules together like Lego bricks.

The Mir space station was a triumph of endurance. It stayed up there for 15 years. It survived fires, collisions with cargo ships, and the total collapse of the government that launched it. When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev was actually stuck on Mir. He went up as a citizen of the USSR and came down to a country called Russia. He’s often called "the last Soviet citizen."

What Can We Learn From This?

The Soviet Union space race story is a weird mix of genuine genius and terrifying negligence. It teaches us that centralized control is great for sprinting—like getting the first satellite up—but it’s terrible for the marathon of sustainable exploration.

If you're looking at the new space race today with SpaceX, Blue Origin, and China, the parallels are everywhere. We see the same tension between "rugged/simple" and "complex/reusable." We see the same drive for national prestige.

Next Steps for History Buffs and Tech Enthusiasts:

If you want to dive deeper into the gritty details of the Soviet Union space race, skip the sanitized textbooks and look for these specific resources:

- Read "Challenge to Apollo" by Asif Siddiqi. It is widely considered the definitive academic history of the Soviet program. It’s huge, but it uses declassified documents that expose the real drama.

- Explore the "Venera" Mission Logs. Look up the actual photos sent back from the surface of Venus. They look like something out of a 1970s sci-fi movie, but they are real, hard-won data from a world that kills everything it touches.

- Check out the N1 Launch Footage. Search for the 1969 N1 explosion videos. Seeing a rocket that size turn into a fireball gives you a visceral understanding of why the Soviets never made it to the moon.

- Visit the Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow (if you're ever able to). Seeing the actual Vostok capsules and the taxidermied remains of Belka and Strelka (the space dogs) puts the scale of their ambition into perspective.

The Soviet Union space race didn't end in a win, but it laid the groundwork for everything we do in orbit today. Without Sputnik kicking the beehive, NASA might never have received the funding to reach the moon. Competition, even the scary kind, is a hell of a motivator.