Space is famously silent. You've heard the tagline from Alien: "In space, no one can hear you scream." That’s because sound, as we typically understand it, is a pressure wave moving through atoms. No air, no sound. But in 2015, everything changed. Humans actually heard the sound of two black holes colliding for the very first time.

It wasn't a bang. It wasn't a roar. Honestly, it was a tiny, upward-sliding "chirp" that lasted less than a second.

This wasn't picked up by a microphone. It was captured by LIGO (the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory). These massive detectors in Washington and Louisiana use lasers to measure changes in distance smaller than the width of a proton. When two black holes—each dozens of times heavier than our sun—spiral into each other at half the speed of light, they don't just move through space. They warp it. They send ripples out into the fabric of reality itself. These are gravitational waves. By the time those ripples reached Earth from 1.3 billion light-years away, they were incredibly faint. But when scientists converted that frequency into audio, it became the most famous sound in the history of physics.

What the Sound of Two Black Holes Colliding Actually Tells Us

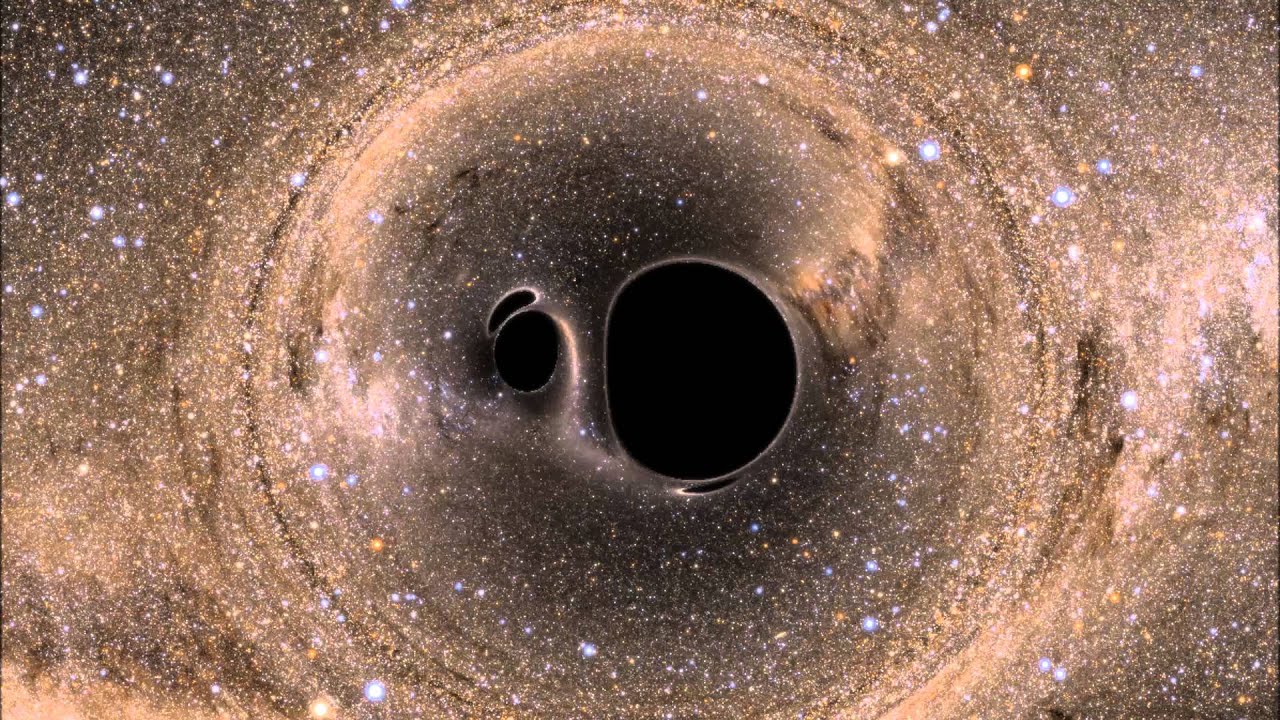

Most people think of black holes as static "holes" in space. They aren't. They are dynamic, spinning, violent concentrations of mass. When two of them get caught in each other's gravity, they perform a "death spiral." This is technically called an inspiral.

As they get closer, they orbit faster. Much faster.

This increase in speed is exactly why the sound of two black holes colliding is a chirp. In physics terms, the frequency of the gravitational waves depends on the orbital frequency of the objects. As the black holes accelerate toward the inevitable "merger," the frequency rises. If you listen to the raw data from the GW150914 event (the first one ever detected), it starts as a low hum and quickly zips up to a high-pitched "whoop."

The physics of the "Ringdown"

After the collision, there’s a brief moment called the ringdown. Imagine hitting a bell with a hammer. The bell vibrates for a second before going still. A newly formed, larger black hole does the same thing. It "rings" as it settles into a perfectly spherical shape. This part of the sound tells us the mass and spin of the final black hole. It's basically the universe's way of sighing after a massive car wreck.

🔗 Read more: How to Remove Yourself From Group Text Messages Without Looking Like a Jerk

How LIGO "Hears" the Invisible

You can't just go out and buy a gravitational wave detector. LIGO is a feat of engineering that seems like science fiction. Each detector has two arms, each four kilometers long, arranged in an "L" shape. A laser is split and sent down both arms.

If a gravitational wave passes through, it actually stretches one arm and squeezes the other.

The change is minuscule. We are talking about $10^{-18}$ meters. To give you some perspective, that is a thousand times smaller than a nucleus of an atom. If the distance between the Sun and the nearest star changed by the width of a human hair, that’s the level of precision we’re dealing with here. When the sound of two black holes colliding vibrates these lasers, the interference pattern of the light shifts.

The data is essentially a waveform. Because the frequencies of these waves happen to fall within the range of human hearing (roughly 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz), we can play them through a speaker.

Why This Isn't Just a Fancy Recording

Before 2015, we were basically looking at the universe with our eyes closed and our ears plugged. Everything we knew came from light—radio waves, X-rays, visible light, infrared. But light can be blocked. Gas and dust clouds hide the most interesting parts of the galaxy.

Gravitational waves are different.

💡 You might also like: How to Make Your Own iPhone Emoji Without Losing Your Mind

They pass through everything. They are the "sound" of gravity itself. By listening to the sound of two black holes colliding, we are seeing parts of the universe that are literally invisible to telescopes. Black holes don't emit light. They are black. But their collisions are the loudest events in the cosmos, radiating more energy in a fraction of a second than all the stars in the observable universe combined.

Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne, and Barry Barish won the Nobel Prize for this. They didn't just find a new object; they gave us a new sense.

Common Misconceptions About the "Chirp"

There’s a lot of junk science out there about what this sounds like. Let’s clear some stuff up.

- Is it loud? No. If you were standing near the black holes (well, you'd be dead), your body would be stretched and squeezed by the waves, but there’s no air to carry a "sound." The "loudness" we talk about is just the amplitude of the spacetime ripple.

- Does every collision sound the same? Not even close. Heavier black holes produce lower-pitched sounds. Smaller ones chirp at a higher frequency. If a neutron star (a dead star the size of a city) hits a black hole, the sound is a long, drawn-out whistle that lasts for minutes rather than a fraction of a second.

- Is it a constant noise? No. Space is quiet until the very last moments of the merger. The detectors usually just hear "noise" from the Earth—ocean waves, trucks driving on nearby roads, even the vibration of atoms in the mirrors.

The Future: LISA and Beyond

Right now, we are limited by the Earth. Ground-based detectors are "noisy." To hear even cooler things, like the sound of two black holes colliding at the centers of galaxies, we have to go to space.

The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) is a planned mission by the ESA and NASA. It will consist of three spacecraft flying in a triangle formation, millions of miles apart. Because it’s in the vacuum of space and has much longer arms, it will hear "deep" bass notes that LIGO can't. It will hear supermassive black holes—monsters millions of times the mass of our sun—merging.

Those sounds won't be chirps. They will be deep, rumbling groans that last for weeks.

📖 Related: Finding a mac os x 10.11 el capitan download that actually works in 2026

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you're fascinated by the "symphony of the cosmos," you don't have to just read about it. You can actually engage with this data directly.

Listen to the Raw Audio

The LIGO Lab at Caltech and MIT has a public database of these "sounds." Search for the "GW150914 chirp" to hear the original 2015 detection. It’s haunting to realize you’re listening to a billion-year-old collision.

Track New Detections

Gravitational wave detections are now happening almost weekly. You can download apps like "Chirp" or "Gravitational Wave Events" that send push notifications to your phone whenever a new collision is detected by the global network (LIGO, Virgo in Italy, and KAGRA in Japan).

Analyze the Data Yourself

LIGO releases their data to the public through the Gravitational Wave Open Science Center (GWOSC). If you have a bit of coding knowledge (specifically Python), they provide tutorials on how to "clean" the noise and extract the sound of two black holes colliding from the raw strain data.

We are officially in the era of multi-messenger astronomy. We aren't just watching the movie of the universe anymore; we finally turned the volume up.