Honestly, if you tried to pitch Soul Man to a studio head in 2026, you’d probably be escorted out of the building by security. Maybe even banned from the lot. It is one of those cinematic artifacts that feels like it belongs to a completely different dimension, let alone a different decade. Released in 1986, the film stars C. Thomas Howell as Mark Watson, a pampered kid who decides that the best way to pay for Harvard Law School—after his dad cuts him off—is to pose as a Black student to win a scholarship.

He does this by taking "tanning pills." Basically, he wears blackface for the entire runtime.

It’s a bizarre premise. Even for the mid-eighties, a decade known for pushing boundaries and, frankly, having a lot of blind spots, Soul Man was a lightning rod. You’ve probably seen clips of it on social media lately, usually accompanied by a caption like "How did this get made?" It’s a fair question. To understand the movie, you have to look at the weird intersection of 80s "colorblind" ideology and the slapstick comedy trends of the era. It wasn't just a random flop; it was a box office hit that grossed over $35 million. People went to see it.

The Plot That Time Forgot

The story kicks off with Mark and his friend Seth (played by Arye Gross) realizing they are in a financial bind. Mark’s father, who is wealthy and somewhat detached, decides Mark needs to learn the value of a dollar and refuses to pay the $50,000 tuition for Harvard. Instead of taking out a loan or, you know, going to a state school, Mark sees an advertisement for a scholarship specifically for African Americans.

He takes an experimental dose of tanning pills, perms his hair, and heads to Cambridge.

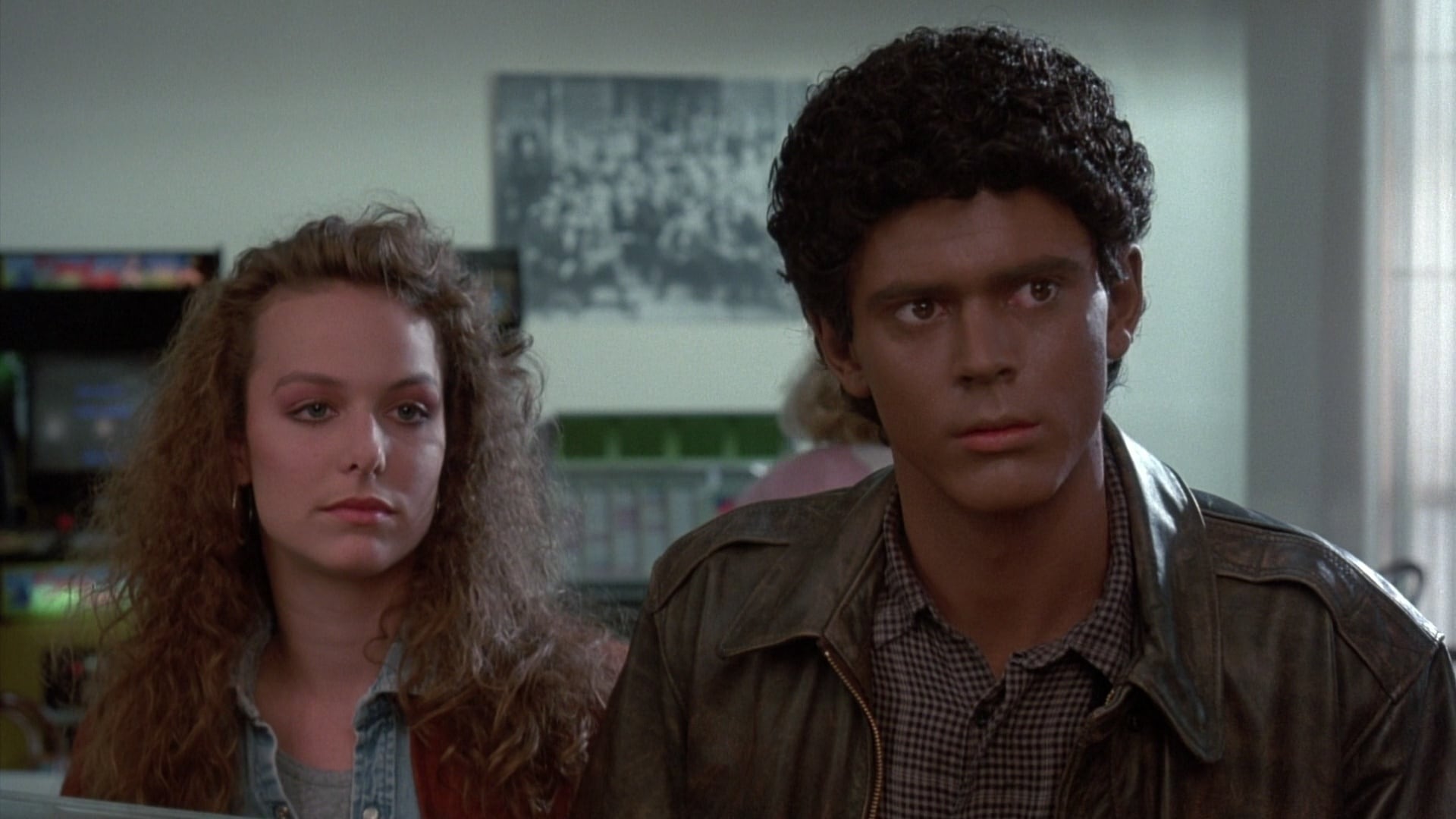

What follows is a series of "fish out of water" tropes that range from the mildly uncomfortable to the genuinely cringeworthy. Mark encounters racism, but because the audience knows he is actually white, the "lesson" often feels unearned or hollow. He falls for Sarah Walker, played by Rae Dawn Chong, who is a single mother working multiple jobs to put herself through the same law school. The irony, of course, is that Mark stole the very scholarship she needed.

Director Steve Miner, who also helmed Friday the 13th Part 2 and Part 3, treats the material like a standard teen romp. There are jokes about basketball. Jokes about "urban" life. It’s a mess of stereotypes wrapped in a "coming-of-age" wrapper.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

The Backlash Was Real Even Then

There’s a common misconception that Soul Man was only deemed offensive in the "woke" era. That’s just not true. When the movie hit theaters in October '86, the NAACP and other civil rights groups were already protesting it. They saw it for what it was: a regressive use of blackface that trivialized the actual struggle of Black students in higher education.

Film critic Roger Ebert gave it one of his most famous "meh" reviews, noting that while the movie tries to be a satire about prejudice, it mostly just ends up being about a white guy feeling sorry for himself. He gave it two stars.

"The problem with 'Soul Man' is that it wants to have it both ways," Ebert wrote. "It wants to use the blackface for cheap laughs, and then it wants to turn around and be a 'very special episode' about the reality of racism."

Rae Dawn Chong has defended the film in various interviews over the years. She’s pointed out that the movie was intended to be a mirror for white audiences, showing them the casual bigotry that existed in "polite" society. In a 2015 interview with The Wrap, she mentioned that it was "actually a very adorable movie" and that it was more about the "silliness of white people."

However, her co-star C. Thomas Howell has had a more complicated relationship with the film's legacy. He’s acknowledged that he wouldn't do it today, though he maintains that the intent wasn't malicious. Intent, as we've learned in the decades since, doesn't always mitigate impact.

Why Does It Still Show Up in Our Feed?

The movie keeps resurfacing because it represents a specific kind of cultural amnesia. We like to think we’ve progressed in a straight line, but Soul Man reminds us of how recently mainstream entertainment thought blackface was a viable comedic device.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

Think about the cast. You’ve got James Earl Jones as the intimidating Professor Banks. You’ve got Leslie Nielsen in a supporting role. These are heavy hitters. Seeing James Earl Jones—the voice of Mufasa and Darth Vader—deliver a lecture to a kid in tanning-pill blackface is surreal. It’s like a glitch in the Matrix.

The Legal and Ethical Grey Areas

From a legal standpoint, the movie touches on the real-world complexities of affirmative action and scholarship fraud. While the film plays it for laughs, "race shifting" for institutional gain is a topic that has cropped up in the news cycle repeatedly over the last decade. Think Rachel Dolezal or various academic scandals. Soul Man accidentally stumbled into a conversation about identity and systemic advantage that we are still having today.

But the movie never goes deep. It stays on the surface. Mark eventually gets "caught" (his tan fades during a high-stress exam), and there is a confrontation with Professor Banks. Banks asks Mark what he learned. Mark gives a speech about how he knows what it's like to be "them."

Banks' response is one of the few grounded moments in the film. He basically tells Mark that he can wash his face and go back to being white, but for everyone else, the reality doesn't end when the credits roll. It’s a brief flash of self-awareness in a movie that is otherwise tone-deaf.

Technical Execution and 80s Aesthetics

If you strip away the central controversy (which is impossible, but let's try for a second), the movie is a time capsule of 80s filmmaking. The synth-heavy soundtrack, the oversized blazers, the lighting that makes everything look like a neon-lit law office—it’s all there.

- The Cinematography: It’s bright, flat, and typical of 80s comedies.

- The Writing: Written by Carol Black, who later co-created The Wonder Years. You can see the DNA of her later work in the attempt at "heart," but it’s misplaced here.

- The Pacing: It moves fast. It’s a tight 104 minutes, which is why it feels like a fever dream.

Modern Perspectives and Cancel Culture

Is Soul Man "canceled"? Not really. You can still find it on various streaming platforms or buy it on Blu-ray. It exists as a teaching tool more than a piece of entertainment. Film schools often use it as a case study in "What went wrong?" or to discuss the history of racial tropes in Hollywood.

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

What’s interesting is how it compares to something like Tropic Thunder. Robert Downey Jr. also wore blackface in that film, but that was a satire of actors who take themselves too seriously. It was a meta-commentary. Soul Man isn't meta. It’s earnest. That earnestness is what makes it so uncomfortable to watch now. It genuinely thinks it’s doing something "good" while using a visual language that is inherently "bad."

Actionable Takeaways for Film History Buffs

If you’re going to dive into the history of Soul Man, or if you're writing about it for a film class, don't just look at the IMDb page. You have to look at the cultural context of 1986.

- Research the 1986 NAACP Protests: Look at the specific statements made by the Los Angeles branch of the NAACP during the film's release. It provides a contemporary counter-narrative to the idea that "people didn't know better back then."

- Compare with "Black Like Me": This was a 1961 book (and later a movie) where a white journalist darkened his skin to travel through the segregated South. Comparing Soul Man to the more serious Black Like Me shows how Hollywood turned a social experiment into a teen comedy.

- Track the Careers of the Cast: Notice how C. Thomas Howell’s career trajectory changed after this. He was a massive star in The Outsiders and Red Dawn, but Soul Man marked a shift in how he was perceived by the industry.

- Watch with Context: If you do watch it, pay attention to the character of Sarah Walker. Rae Dawn Chong’s performance is actually the strongest thing in the movie, and her character is the only one with real stakes.

The legacy of Soul Man is one of discomfort. It’s a movie that tried to "solve" racism by having a white guy put on a costume, and in doing so, it became one of the most famous examples of the very thing it was trying to critique. It’s messy, it’s controversial, and it’s a vital part of understanding how Hollywood’s depiction of race has evolved—or hasn't—over the last forty years.

Instead of burying it, analyzing it allows us to see the cracks in the "post-racial" facade of the 80s. It’s a reminder that good intentions, without actual perspective, often lead to some of the most baffling decisions in cinematic history.

To fully understand the impact of the film, look up the original New York Times review from October 1986. It captures the immediate confusion and frustration critics felt at the time, proving that the conversation we're having today is decades in the making. Understanding these primary sources gives a much clearer picture of why this film remains a "must-know" for anyone studying the intersection of race and American media.