It is a bloody, chaotic mess of a poem. If you ever sat through a survey course on Western Lit, you probably remember The Song of Roland as that dusty French epic where everyone dies for "honor" or some other vague medieval concept. But honestly? Most people get the story completely sideways. They see it as a simple piece of propaganda. It isn’t. Not really.

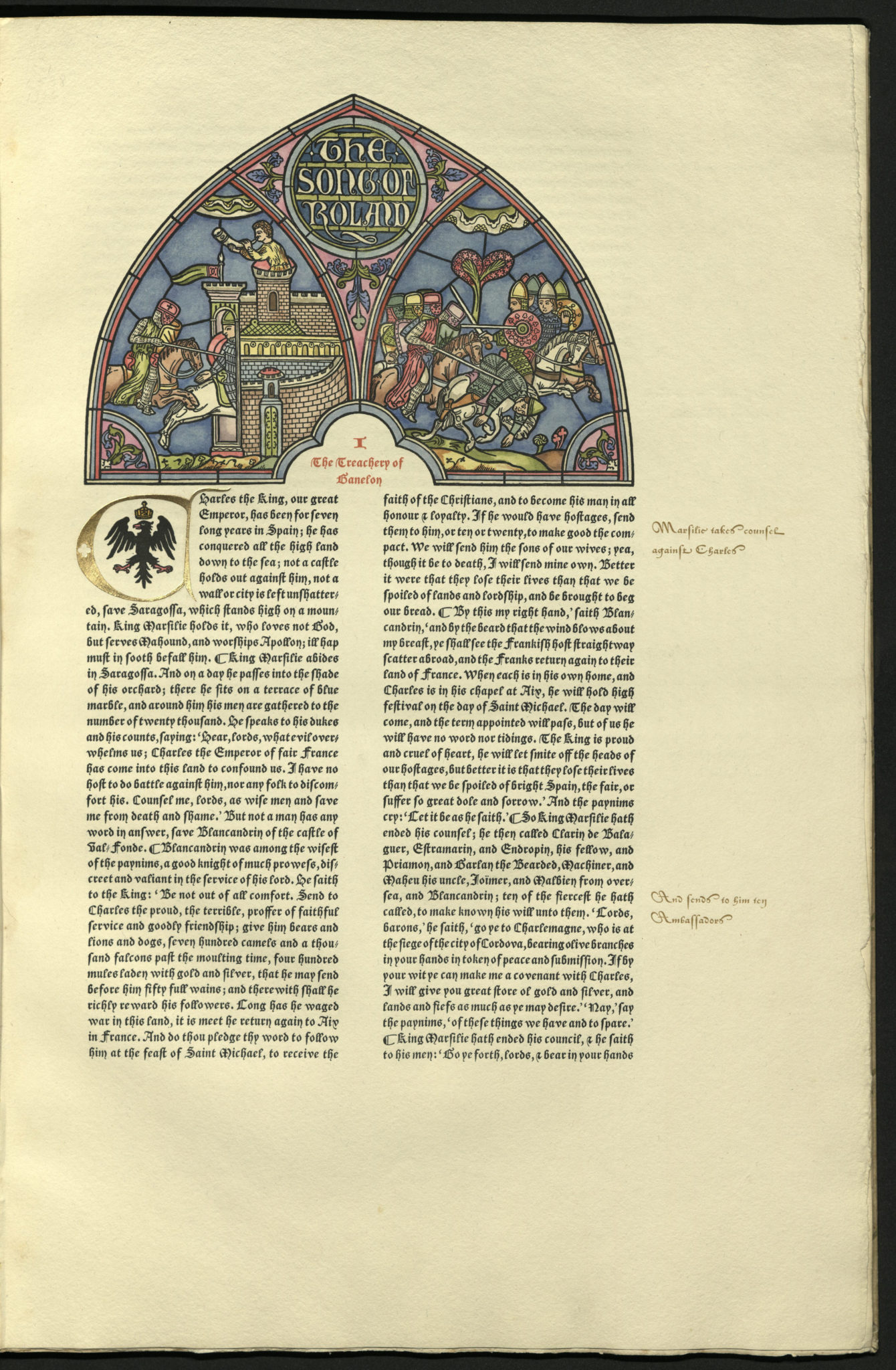

The poem, or La Chanson de Roland, is the oldest surviving major work of French literature. It dates back to the late 11th century, somewhere between 1040 and 1115. It tells the story of a real-life ambush that happened in 778 AD at Roncevaux Pass. Charlemagne was retreating from Spain. His rear guard got slaughtered. Among the dead was a guy named Hruodlandus. That’s our Roland.

But here is the thing: the historical Roland died fighting Basques. He died because of a tactical error. By the time the poem was actually written down—centuries later—the Basques had been swapped out for "Saracens" (Muslims), and the skirmish had been inflated into a cosmic battle between good and evil. It’s the ultimate example of "history is written by the winners," except in this case, the winners were the poets who survived the losers.

Why the Song of Roland Still Hits Different

Why do we still talk about this? Because it’s basically the blueprint for every action movie ever made. You have the hero (Roland), the wise mentor (Charlemagne), the foil (Oliver), and the absolute rat of a traitor (Ganelon).

The drama isn't just about the fighting. It’s about a massive ego trip. When the rear guard is surrounded by 100,000 Saracens, Oliver—Roland’s best friend and a much more sensible guy—begs Roland to blow his ivory horn, the Oliphant, to call Charlemagne back for help. Roland says no. He says no three times. He thinks it would be a "shame" to his lineage. He’d rather watch his men get hacked to pieces than admit he needs a hand.

It’s frustrating. You read it and you want to scream at the page. Roland’s "heroism" is actually a form of toxic pride (démesure). It’s only when he’s literally the last man standing, with his brains starting to leak out of his ears from the pressure of blowing the horn too hard later on, that he finally admits defeat. It's dark. It's gritty. It’s way more complicated than a simple "go team" story.

💡 You might also like: Dutch Bros Menu Food: What Most People Get Wrong About the Snacks

The Ganelon Problem

We need to talk about Ganelon. Everyone loves to hate him. He’s the guy who betrays the Franks to King Marsile of Zaragoza. But if you look at the text closely, Ganelon doesn't think he's a traitor. He thinks he’s settling a legal feud.

In the medieval mind, a "private feud" was a legitimate way to handle beef. Roland nominated Ganelon for a dangerous diplomatic mission that was basically a death sentence. Ganelon felt insulted. He decided to get back at Roland by orchestrating the ambush. In his head, he was just playing the game. The tragedy is that his personal grudge ended up destroying an entire army. It shows how fragile a kingdom is when the people at the top care more about their feelings than their duty.

The Battle of Roncevaux: Fact vs. Fiction

Most students of history get tripped up here. They think the poem is a primary source. It’s not. It’s historical fiction at best, and pure fantasy at worst.

- The Enemy: Historically, Charlemagne was fighting Basques (Christians). The poem turns them into a massive Muslim army because, during the Crusades (when the poem was written), that was the "relevant" enemy.

- The Scale: The real ambush was a small-scale mountain hit-and-run. The poem turns it into a clash of hundreds of thousands.

- The Ending: Charlemagne supposedly stayed in Spain for years to avenge Roland. In reality? He left pretty much immediately. He had a kingdom to run and bigger problems on his borders.

Scholar Joseph Bédier famously argued that these epic poems (chansons de geste) were written to entertain pilgrims on the way to Santiago de Compostela. They weren't history books. They were "road trip" stories. They were meant to be sung in taverns and courtyards. Think of it like a medieval Netflix series. You want the drama high and the facts flexible.

The Weirdness of Roland’s Death

Roland’s death scene is the longest, most drawn-out exit in literary history. He doesn't just die. He tries to break his sword, Durendal, so the enemy can’t have it. He fails because the sword is basically indestructible (it allegedly contains a tooth of Saint Peter and some hair from Saint Denis).

📖 Related: Draft House Las Vegas: Why Locals Still Flock to This Old School Sports Bar

Then he lays down under a pine tree, faces Spain so everyone knows he died a conqueror, and offers his glove to God. Angels literally swoop down—Gabriel and Michael—to carry his soul to Paradise.

It’s over the top. It’s meant to be. But the psychological weight is real. Roland dies of a burst temple from blowing his horn, not from a sword wound. He dies of the physical effort of finally being humble enough to ask for help. That is a heavy metaphor for a guy written in the 1100s.

What We Can Learn From the Verse

The style is weirdly repetitive. It uses something called laisses—stanzas of varying length. There’s no rhyme, just assonance (vowel sounds matching at the end of lines). It creates this hypnotic, driving rhythm.

- Short sentences create tension.

- Longer descriptions build the scale.

- The repetition reinforces the inevitability of the tragedy.

It’s a masterclass in pacing. Even if you hate the characters, you can’t stop reading because the momentum is relentless. It feels like a landslide. Once Ganelon makes his deal, you know exactly where this is going, and you’re just waiting for the impact.

The Real-World Legacy

The Song of Roland didn't just sit in a library. It shaped the concept of chivalry. It defined what it meant to be a "knight" for centuries. It influenced everything from the Nibelungenlied in Germany to the legends of King Arthur.

👉 See also: Dr Dennis Gross C+ Collagen Brighten Firm Vitamin C Serum Explained (Simply)

Even today, you see its DNA in things like Lord of the Rings. Boromir’s death? That’s Roland. The horn of Gondor? That’s the Oliphant. The idea of a doomed rear guard holding the line while the king rides away? That’s Roncevaux.

But we have to be careful. This poem has been used by nationalist movements to justify "us vs. them" mentalities. It’s been twisted to support colonialism and religious warfare. When you read it, you have to see the beauty in the poetry while acknowledging the ugliness of the bias. It’s a product of its time—a time of holy wars and brutal feudalism.

Actionable Insights for Readers

If you’re going to dive into this, don't just grab the first translation you see. Look for one that preserves the "laisse" structure. The Dorothy L. Sayers translation is classic, even if it feels a bit old-fashioned now. She captures the grit.

- Read it aloud. These poems were meant for the ear, not the eye. The rhythm makes way more sense when you hear the beats.

- Watch the "Parallelism." Notice how Roland and Oliver’s arguments repeat. It’s not a mistake; it’s a rhetorical device to show the stalemate between "wisdom" and "bravery."

- Check the footnotes. The political landscape of 11th-century France is baked into every line. Understanding the tension between the Barons and the King adds a whole layer of depth to the betrayal.

- Look for the "AOI." In the Oxford Manuscript (the oldest version), many stanzas end with the letters "AOI." No one knows what it means. It’s one of literature’s great mysteries. Some think it’s a musical cue, others think it’s a shout. Decide for yourself.

The Song of Roland isn't a dead text. It’s a loud, bloody, complicated scream from the past. It tells us that even the greatest heroes are flawed, that pride is a killer, and that history is often just a story we tell to make sense of our losses. It’s not always pretty. But it’s definitely not boring.

To truly appreciate the scope of this work, compare the poetic version of Roland's death with the historical account in Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne. Einhard gives the event a single paragraph. The poet gives it thousands of lines. That gap—the space between what happened and what we remember—is where the real magic of literature happens. It’s why we still know Roland’s name over a thousand years after he bled out in a mountain pass.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

- Locate a bilingual edition: Seeing the Old French alongside the English helps you spot the original wordplay and the harsh, percussive sounds of the original language.

- Map the route: Look at a topographical map of the Roncevaux Pass (Roncesvalles) in the Pyrenees. Seeing the actual narrowness of the terrain makes the tactical disaster of the rear guard much more visceral.

- Research the "Twelve Peers": Investigate the legendary status of the other knights, like Archbishop Turpin, who fought alongside Roland. Their inclusion highlights the medieval ideal of the "fighting priest," a concept that seems bizarre today but was central to the poem’s original audience.