New York City in the mid-seventies was a mess. Garbage strikes, financial collapse, and a palpable sense of dread hung over the five boroughs like a thick humid blanket. Then came the ".44 Caliber Killer." Most people know him now as David Berkowitz, or the Son of Sam killer, but back then, he was just a ghost with a gun. He turned the city into a shooting gallery, specifically targeting young women with long, dark hair and couples sitting in parked cars. It wasn’t just the murders that paralyzed New York; it was the letters. The taunting notes sent to Jimmy Breslin and the NYPD created a media circus that essentially invented the modern true crime obsession.

He wasn't some criminal mastermind. Honestly, looking back at the forensics and the police work, it’s kind of a miracle—and a tragedy—it took so long to catch him.

The .44 Caliber Terror Begins

The first shots weren't even recognized as a serial pattern right away. On July 29, 1976, Donna Lauria and Jody Valenti were sitting in a car in the Bronx. A man approached, pulled a heavy .44 Bulldog revolver from a paper bag, and fired. Donna died instantly. Jody survived. At the time, police thought it might be a random hit or a case of mistaken identity. They had no idea this was the opening act of a year-long nightmare.

By the time the Son of Sam killer struck again in October and November, the patterns were emerging. He liked the dark. He liked the quiet streets of Queens and the Bronx. He liked the element of surprise. The weapon was always the same: a massive .44 caliber Charter Arms Bulldog. It’s a loud, violent gun. Not the kind of thing a subtle person uses.

The city's reaction was pure panic. You have to remember, this was 1977. There were no cell phones. No Ring cameras. If you were out late in a parked car, you were completely off the grid. Thousands of women across New York City started cutting their hair short or dyeing it blonde because the word on the street was that the killer only went after brunettes. Wig shops did a massive business that summer. People stayed indoors. Disco clubs, usually packed, saw their dance floors empty out early.

The Letters and the Persona

What really set Berkowitz apart from other killers of that era was his desire for a dialogue. He didn't just want to kill; he wanted to be a character in the city's story. He left a letter near the bodies of Alexander Esau and Valentina Suriani in April 1977. It was addressed to NYPD Captain Joseph Borrelli.

In that frantic, rambling note, he called himself "Son of Sam" for the first time. He wrote about "Papa Sam" who kept him locked in an attic and demanded blood. He called himself a "monster" and a "behemoth." It was theatrical. It was terrifying. It was also, as we later found out, largely a fabrication designed to make him look insane.

Then came the letters to Jimmy Breslin, the famous columnist for the Daily News. Breslin was the voice of the working class, and Berkowitz knew it. He wrote to Breslin, "I am still here. Like a spirit roaming the night." The Daily News sold over a million copies the day they printed excerpts. It was a symbiotic, toxic relationship between a murderer and the media. The killer got the fame he craved, and the papers got the headlines that saved their bottom lines during a fiscal crisis.

🔗 Read more: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

The Blackout and the Breaking Point

July 13, 1977. The lights went out. A massive power failure plunged New York City into darkness for 25 hours. Looting broke out. Arson turned parts of the city into a war zone. And everyone—everyone—was waiting for the Son of Sam killer to use the darkness as a cover for a massacre.

He didn't.

Maybe the chaos was too much even for him. Or maybe he preferred the quiet, lonely streets over the riotous energy of the blackout. But he didn't stay quiet for long. On July 31, he struck for the final time in Brooklyn, killing Stacy Moskowitz and blinding Robert Violante. This was the turning point. Detectives had been working 24/7, but they were exhausted. They had thousands of "leads" that went nowhere.

The break in the case didn't come from a brilliant psychological profile or a high-tech forensic discovery. It came from a parking ticket.

How a Parking Ticket Ended the Nightmare

A witness named Cacilia Davis was walking her dog near the site of the final shooting. She saw a man walking toward a car that had a yellow ticket on the windshield. She felt something was off. He looked at her. She bolted.

Later, she told police about the car.

The NYPD started sifting through every ticket issued in that area on that night. They found a ticket issued to a 1970 four-door Ford Galaxie. The owner? David Berkowitz. 35 Pine Street, Yonkers.

💡 You might also like: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

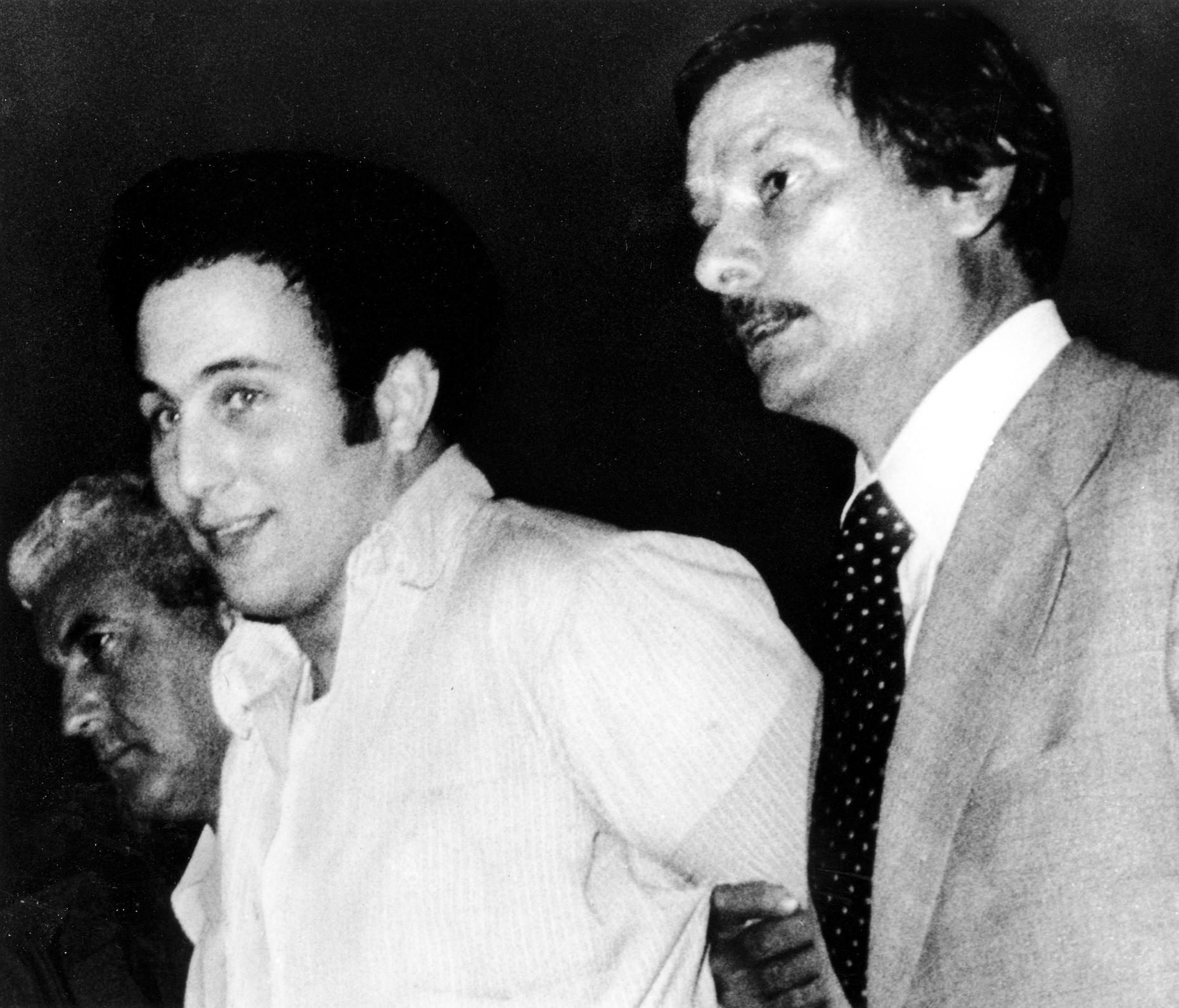

When detectives arrived at the address on August 10, 1977, they saw the car. They looked inside. They saw a rifle in the back seat and a letter addressed to the police. They waited. When Berkowitz walked out to the car, they moved in. Detective Falotico pointed his gun at the man. Berkowitz reportedly smiled and said, "Well, you got me."

He didn't look like a monster. He looked like a bored postal worker. He was pudgy, soft-spoken, and had what the media called a "cherubic" face. It was a chilling contrast to the violence he had inflicted.

The "Demon Dog" Myth

During the interrogation, Berkowitz dropped the bombshell that has fueled conspiracy theories for decades. He claimed he wasn't acting alone. He said his neighbor, Sam Carr, had a black Labrador Retriever named Harvey. According to Berkowitz, the dog was possessed by an ancient demon that barked orders at him, demanding he go out and kill "pretty girls."

It was a sensational story. The "Demon Dog" became a staple of tabloid lore. But years later, Berkowitz admitted he made the whole thing up. He wanted a "crazy" defense. He wanted to be a legend. In reality, he was a deeply resentful, lonely man who hated the world and found a way to make it notice him.

Was He Really Alone?

This is where the story gets murky. While the official line is that Berkowitz acted alone, some investigators, most notably the late journalist Maury Terry, argued for years that the Son of Sam killer was actually a cult. Terry’s book, The Ultimate Evil, suggests that Sam Carr’s sons, John and Michael, were involved in a satanic group with Berkowitz.

Both Carr brothers died under mysterious circumstances shortly after Berkowitz’s arrest. John died of a gunshot wound in North Dakota; Michael died in a car accident in Manhattan. Berkowitz himself has, at various times, supported Terry’s claims, stating in prison interviews that he was part of a "group" and didn't pull the trigger in every shooting.

Most law enforcement officials dismiss this. They see it as a killer trying to deflect blame or stay relevant. But for some of the victims' families, the "lone gunman" theory has never quite sat right. The composite sketches released during the manhunt looked like several different men, not just one. It’s one of those true crime rabbit holes that never quite hits bottom.

📖 Related: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

The Legacy: Son of Sam Laws

New York didn't just move on. The legal system changed forever because of this case. When rumors started swirling that Berkowitz was being offered massive sums of money for his life story, the New York State Legislature flipped out. They passed what is now known as the "Son of Sam Law."

Basically, it prevents criminals from profiting from the publicity of their crimes. If a killer writes a book or sells movie rights, that money goes into a fund for the victims. While parts of the original law were struck down by the Supreme Court in 1991 (Simon & Schuster, Inc. v. Members of the New York State Crime Victims Board) because they were too broad, the core idea remains in many states today. We decided as a society that you shouldn't get rich by being a monster.

Realities of the Case

If you're digging into this, ignore the sensationalized movies for a second. Look at the numbers. Six dead. Seven wounded. Hundreds of thousands of lives disrupted by fear.

- The Weapon: The .44 Bulldog is an incredibly powerful, short-range weapon. It’s hard to aim. This suggests Berkowitz was shooting from very close range, often right at the car window.

- The Victims: There was no specific "type" other than young people in cars. The "brunette" theory was mostly a media creation that Berkowitz leaned into.

- The Capture: It was pure grunt work. Checking parking tickets isn't sexy, but it’s what caught one of the most famous serial killers in history.

What to Do if You're Researching This Further

Don't just take the Netflix documentaries at face value. If you really want to understand the atmosphere of 1977, do these things:

- Read "The Ultimate Evil" by Maury Terry. Even if you don't believe the conspiracy, it shows the massive holes in the original investigation.

- Look up the Jimmy Breslin columns. You can find archives online. They capture the raw, terrified energy of the city in a way a modern writer can't replicate.

- Check the NYPD's "Operation Omega" files. This was the name of the task force. Their internal struggle with false leads and public pressure is a masterclass in how not to run a high-profile investigation.

- Verify the timeline. Many people confuse the blackout with a specific shooting. They happened in the same summer, but they were separate events that fed into the same collective trauma.

The Son of Sam killer remains a fixture in the American psyche because he represented the random, senseless violence of an era where things felt like they were falling apart. He wasn't a genius. He wasn't a demon. He was a man with a gun and a parking ticket he forgot to pay.

Next time you see a yellow slip on a windshield, just remember—that’s how the biggest manhunt in New York history ended.