Imagine standing at the edge of a cliff in the Andes, 14,000 feet up, looking at a road that stretches for miles through solid rock. You aren't looking at a miracle. You're looking at the result of one of the most rigid, yet oddly functional, social systems ever designed. The social structure of the Inca Empire wasn't just about who wore the biggest gold earrings or who sat on the throne. It was a massive, living machine.

They called it Tawantinsuyu. Four parts together.

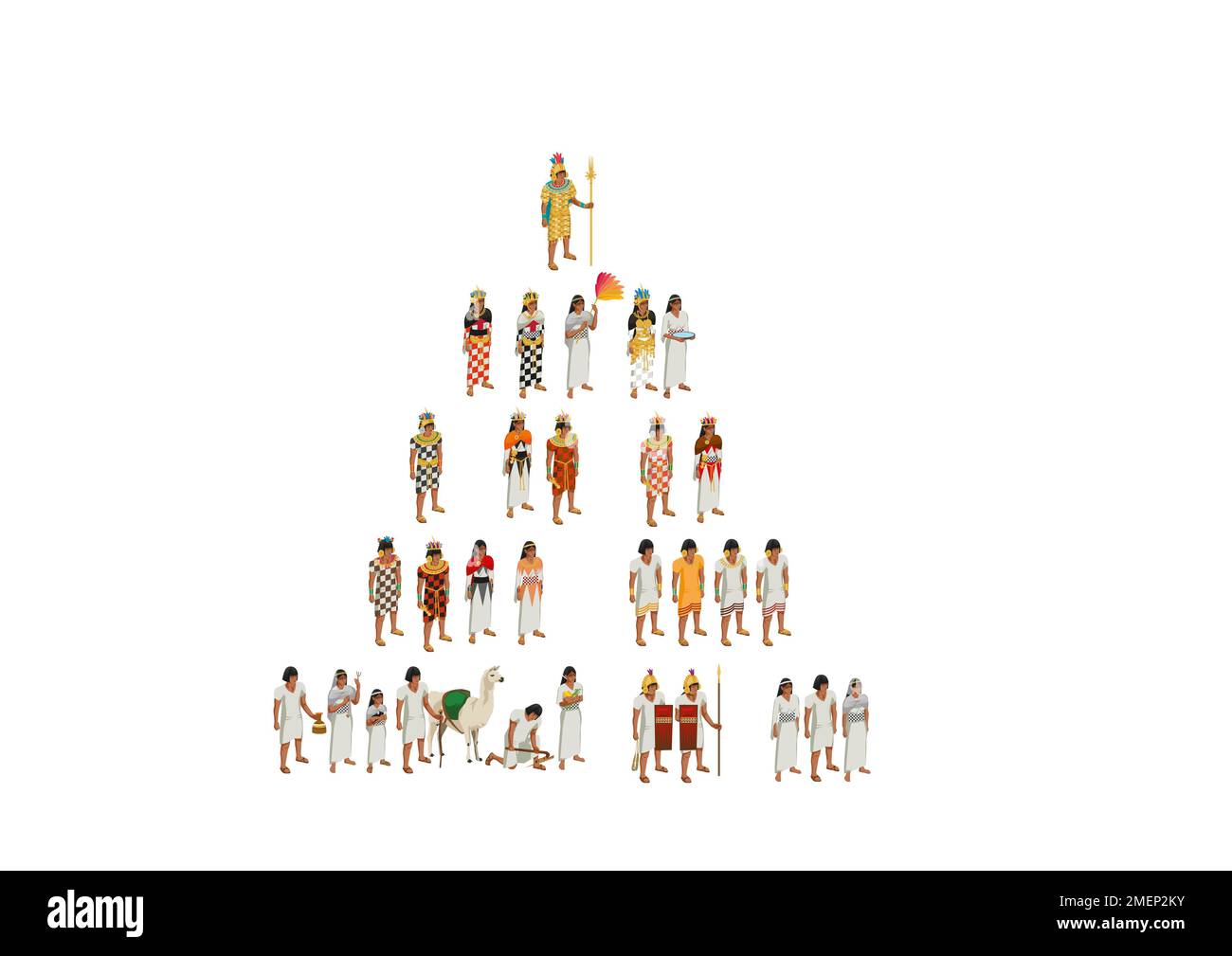

Honestly, the way we usually learn about empires is through battles and kings, but with the Inca, the real story is in the logistics. It’s in the ayllu. It’s in the tax you paid with your sweat instead of your coins. If you didn't fit into the pyramid, you basically didn't exist. This wasn't a "pull yourself up by your bootstraps" kind of place. You were born into a slot, and you stayed there, but that slot guaranteed you didn't starve.

The Sapa Inca: A God With Real Problems

At the very top sat the Sapa Inca. He wasn't just a king; he was the "Son of the Sun." People couldn't even look him in the eye. When he traveled, he sat on a golden litter, and a small army of servants literally swept the ground in front of him so his feet wouldn't touch common dirt.

But here’s the thing.

Being a god-king was exhausting. The Sapa Inca owned everything. Every blade of grass, every llama, every potato. But owning everything means you're responsible for everything. If a harvest failed in the south, it was his divine failure. To manage this, the Sapa Inca relied on the Coya, his primary wife, who held her own court and possessed significant influence over religious matters and female social circles.

The royal lineage, or panaqa, was a weirdly complicated mess. When a Sapa Inca died, his successor got the title, but the dead guy kept the property. The mummified body of the previous ruler stayed in his palace, "ate" meals, and was consulted on state affairs. This meant every new ruler had to conquer new lands just to build his own wealth. Talk about pressure.

The High Nobility and the "Big Ears"

Below the Sun King were the aristocrats. The Spanish called them orejones—"big ears."

Why?

👉 See also: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

Because they wore massive earplugs that stretched their lobes down to their shoulders. It was the ultimate "I’m important" flex. These were the descendants of the original Inca who founded Cusco. They held the top jobs: generals, high priests, and the Apu, who were the governors of the four quarters of the empire.

Then you had the "Incas by Privilege." As the empire grew too fast for the original families to manage, they had to promote people. If your tribe was loyal and useful, you might get bumped up to a lower tier of nobility. It was a bureaucratic necessity. You can't run a 2,500-mile-long empire with just your cousins.

The Curacas: The Middle Managers of the Andes

If the Sapa Inca was the CEO, the Curacas were the regional managers who actually kept the lights on. They weren't always Inca by blood. Often, they were the local leaders of tribes the Inca had conquered. The Inca were smart—instead of killing every leader they met, they’d say, "Keep your job, just work for us now."

The Curacas were exempt from manual labor. They got to wear fine cumbi cloth. But they had a quota. They had to make sure their people produced enough corn, cloth, and labor. If the quota wasn't met, the Curacas were the ones who had to answer to Cusco.

The Ayllu: The Heartbeat of the Empire

This is where the social structure of the Inca Empire gets real for 95% of the population. Forget the gold. The ayllu was the foundation.

An ayllu was a group of families who lived together, worked the same land, and shared everything. You didn't own your farm. The state "loaned" it to you. Every year, the land was redistributed based on how many people were in your family. Had a new baby? Here’s more land. Did someone pass away? The state took some back.

It was communalism on a massive scale.

- You worked your own land to eat.

- You worked the Curaca's land to keep him happy.

- You worked the "Sun’s land" to fund the temples.

- You worked the "Inca’s land" to fill the state storehouses.

The Inca didn't have money. They had Mit'a. This was a labor tax. Every able-bodied man had to spend part of the year doing "public works." That’s how the roads were built. That’s how Machu Picchu was carved into a mountain. You paid your taxes with your muscles.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

The Mitimaes: Forced Relocation for Stability

The Inca were masters of psychological and social control. If they conquered a rebellious tribe, they didn't just leave them there to plot. They used mitimaes. They would pick up thousands of people and move them to a loyal part of the empire. Then, they’d take loyal subjects and move them into the rebellious territory.

It broke local power. It mixed cultures. It made sure everyone spoke Quechua.

It was brutal, honestly. You'd be ripped from your ancestral home and dropped in a completely different climate just because the Sapa Inca wanted to ensure political stability. But it worked. It turned a collection of warring tribes into a unified state in less than a century.

Specialized Classes: The Chosen Women and the Yanacona

Not everyone was a farmer.

The Aclla, or "Chosen Women," were girls selected for their beauty or talent. They lived in temples, wove the finest cloth in the world, and brewed the chicha (corn beer) used in ceremonies. Some became wives of nobles; others remained "Virgins of the Sun."

Then there were the Yanacona. These people were removed from the ayllu system entirely. They were permanent servants to the nobility. They didn't pay the Mit'a tax because their whole life was service. It’s a bit of a grey area—not quite slaves, but definitely not free.

The Decimal System of Control

The Inca loved order. They organized the entire population into a decimal hierarchy. One leader for 10 households, another for 50, another for 100, and so on, all the way up to 10,000.

Every single person was accounted for on a quipu—those knotted strings you’ve probably seen in museums. Since they didn't have a written language in the way we think of it, these strings tracked everything: births, deaths, how many bushels of quinoa were in a warehouse in Huánuco Pampa, and how many men were available for the army.

🔗 Read more: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

If you were a commoner, your life was scheduled. There were "laws" for everything. You couldn't travel without permission. You had to wear the dress of your specific region. If you were caught being lazy, you could be punished. "Ama sua, ama llulla, ama qhella" was the motto: Don't steal, don't lie, don't be lazy.

Why the System Actually Worked

It sounds like a nightmare of bureaucracy, but for the average person, there was a trade-off. The Inca storehouses (qullqa) were packed. In years of drought, the state opened those storehouses and fed the people. No one went hungry. The social structure of the Inca Empire provided a safety net that was centuries ahead of its time.

The complexity of the system is best seen in the works of Pedro Cieza de León, a Spanish chronicler who actually admired how organized the Inca were compared to the chaos of early colonial rule. He noted that even in the most rugged terrain, the social order ensured that travelers were fed and roads were maintained.

The Breakdown

So, why did it fall? When the Spanish arrived, the system was already cracking. A civil war between two brothers, Atahualpa and Huáscar, had split the nobility. Smallpox had already traveled south from Central America, killing the Sapa Inca Wayna Qhapaq and his heir before the Spanish even set foot in the Andes.

The very thing that made them strong—the absolute centralization of power—became their weakness. Once the Spanish captured the Sapa Inca, the rest of the machine didn't know how to function without the "head."

Actionable Insights for Understanding the Inca

If you’re looking to truly grasp how this social pyramid functioned beyond the textbooks, focus on these three things:

- Study the Quipu: Don't look at them as "beads on a string." Look at them as the Excel spreadsheets of the 15th century. They are the key to understanding how a pre-literate society managed millions of people.

- Analyze the Architecture: When you see an Inca wall, don't just admire the stones. Look at the labor. Each stone represents the Mit'a tax—thousands of hours of collective human effort mandated by the social hierarchy.

- Explore the "Vertical Archipelago": The Inca didn't just live in one spot. To understand their social survival, look at how one ayllu would send members to the coast for fish, the mid-lands for corn, and the high peaks for potatoes. It was a social strategy for ecological survival.

The Inca didn't build an empire on gold; they built it on people. Every person had a place, every person had a job, and every person was a stitch in a massive, woven tapestry that stretched across the spine of South America.