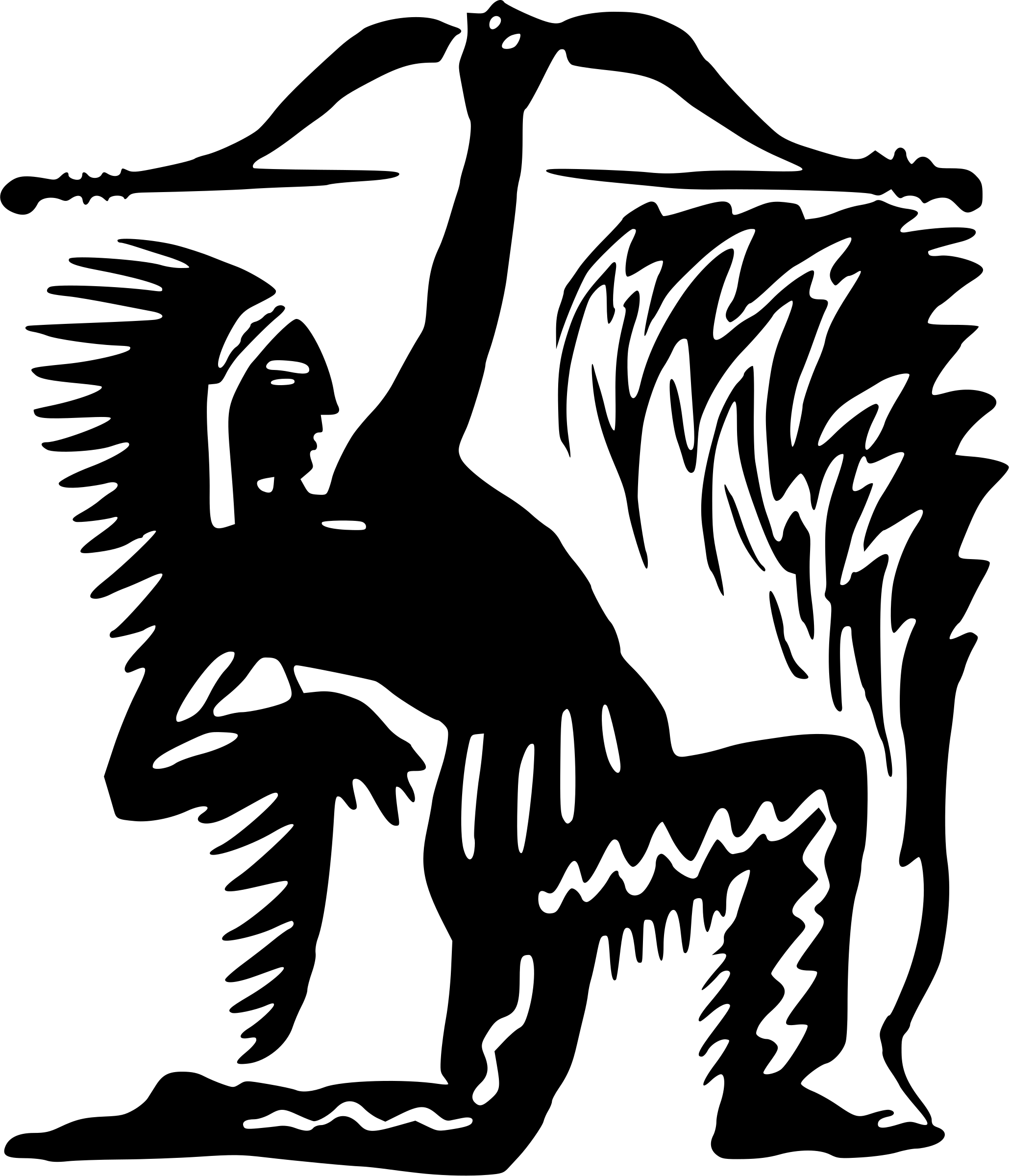

You’ve seen it a thousand times. Maybe it was on a dusty road sign in the Southwest, a high school gym wall, or a silver coin tucked away in a drawer. That sharp, dark profile—the silhouette of Native American imagery—is one of the most recognizable visual motifs in the world. It’s a shape that carries a heavy, complicated weight. Honestly, it’s kinda strange how a simple outline can trigger everything from deep cultural pride to intense political debate, but that’s the power of a silhouette. It strips away the individual and leaves you with an icon.

But icons are tricky. They can be beautiful, and they can be reductive. When we look at that specific profile, usually featuring a feathered headdress or a braided warrior pose, we aren't just looking at art. We’re looking at how history has been framed, sold, and remembered.

The Psychology Behind the Profile

Why does the silhouette of Native American figures resonate so much more than a detailed photograph might? Basically, it’s about the "closure" principle in psychology. When you see a silhouette, your brain has to fill in the blanks. You aren’t seeing a specific person like Chief Joseph or Red Cloud; you’re seeing an idea. For many, that idea is "strength" or "connection to the land." For others, it’s a painful reminder of how Indigenous identity was frozen in time by 19th-century photographers like Edward S. Curtis.

👉 See also: Iocovozzi Funeral Home Obituaries: Why This Small-Town Record Matters More Than Ever

Curtis is a name you have to know if you want to understand this. He spent decades documenting "The Vanishing Race." While his work is visually stunning, he often staged photos, providing props and clothing that didn't always match the specific tribe he was shooting. He wanted that perfect, stoic silhouette. He wanted the romance. Because of him, the world got used to seeing Native Americans as figures of the past, backlit by a setting sun, rather than as modern people living in the present.

Real World Impact: From Coins to Logos

Look at the Buffalo Nickel. Released in 1913, James Earle Fraser’s design is probably the most famous silhouette of Native American history in existence. Fraser claimed it wasn't a portrait of one man but a composite of three: Iron Tail (Lakota), Two Moons (Cheyenne), and Big Tree (Kiowa).

It’s a masterpiece of minting. But it also solidified a very specific aesthetic. It’s that sharp nose, the braided hair, and the feathers. That specific silhouette became the "official" look of Indigeneity in the American subconscious. You see it mirrored in the controversial history of sports logos, like the former Washington Redskins or the Cleveland Indians’ "Chief Wahoo," though Wahoo was a caricature rather than a silhouette. The shift away from these images isn't just about "political correctness." It’s about the fact that a silhouette, by definition, lacks a face. It lacks a voice.

Art vs. Stereotype: Knowing the Difference

There’s a massive difference between a silhouette of Native American heritage created by an Indigenous artist and one bought at a hobby shop for three dollars. Indigenous artists today, like those featured in the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), use silhouettes to subvert expectations.

Take the work of someone like Wendy Red Star. She often uses historical imagery but adds her own annotations to reclaim the narrative. When an Indigenous artist uses a silhouette, it’s often a commentary on invisibility. They’re saying, "This is all you see, but there is so much more behind the shadow."

If you're a designer or a collector, you’ve got to ask: where did this image come from?

Is it a generic "Indian" profile?

Does it respect tribal-specific regalia?

Or is it just a "cool" shape?

Most generic silhouettes you find in clip art galleries are a mess of different cultures. They’ll put a Plains-style headdress on a figure and call it a day. It’s the equivalent of putting a French beret on a guy in a kilt and calling him "European." It just doesn't work if you actually care about the details.

The Longevity of the "End of the Trail"

One specific silhouette has basically defined the genre for over a century: The End of the Trail.

✨ Don't miss: Why How to Deter Cats From Peeing in House Is Actually a Medical Puzzle (and How to Solve It)

Created by James Earle Fraser (the nickel guy) for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, it depicts a Native American man slumped over his horse, exhausted and defeated. It was meant to symbolize the supposed "vanishing" of Indigenous people.

It’s everywhere. You’ve seen the silhouette of Native American defeat on belt buckles, posters, and book covers. It’s actually kinda tragic how popular it stayed. While Fraser might have meant it as a sympathetic tribute, it reinforced the idea that Native Americans were a people of the past, destined to fade away.

But they didn't.

Today, tribal nations are some of the fastest-growing economies in several U.S. states. There are Native American astronauts, tech CEOs, and poets laureate. The silhouette of the "defeated warrior" doesn't match the reality of 2026. The silhouette is static. The people are not.

How to Approach Native Imagery Responsibly

If you are looking to incorporate this kind of imagery into your life or work, you have to be intentional. There’s a fine line between appreciation and appropriation.

- Prioritize Indigenous Creators. If you want a piece of art that features a silhouette of Native American life, buy it from a Native artist. Check out platforms like the SWAIA Santa Fe Indian Market. You’re getting a story, not just a shape.

- Check the Regalia. Feathers aren't just decorations. In many cultures, they are earned honors. A silhouette that tosses feathers around haphazardly is basically mocking a military medal.

- Context is King. Is the image being used to sell a "vibe," or is it honoring a specific history? If it’s for a "Boho" wedding invite, maybe skip it. If it’s for a documentary on the Long Walk of the Navajo, it makes sense.

- Learn the Names. Behind every silhouette was a real person. Instead of looking for "Native silhouette," look for the history of the Haudenosaunee, the Diné, or the Seminole.

The Visual Evolution

We are seeing a shift. The "classic" silhouette is being replaced by more nuanced representations. We’re seeing silhouettes of people in business suits, silhouettes of scientists, silhouettes of mothers. The shadow is finally starting to match the person standing in the light.

It’s important to remember that for a long time, these silhouettes were all people had. In an era where Indigenous languages were banned and ceremonies were illegal (under the Code of Indian Offenses), sometimes a simple image was a way to hold onto an identity that the government was trying to erase.

📖 Related: Is Rick Owens Demonic? What Most People Get Wrong About the Dark Lord of Fashion

But we aren't in 1883 anymore.

Moving Beyond the Shadow

When you see a silhouette of Native American figures now, look at it with a critical eye. Appreciate the linework, sure. But also acknowledge what’s missing. A silhouette is a shadow, and shadows only exist because there’s something solid blocking the light.

To really respect the culture, you have to look past the shadow and see the solid reality of the 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S. today. Each has its own government, its own art, and its own future.

Stop looking at the silhouette as a decorative object. Start seeing it as a doorway to a much larger, much more vibrant room.

Next Steps for Deeper Understanding:

- Audit Your Sources: If you own products featuring these silhouettes, research the company. Do they give back to Indigenous communities? Do they have any Native people on their board?

- Visit Tribal Museums: Instead of relying on 1915-era art, visit the National Museum of the American Indian in D.C. or local tribal centers like the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City.

- Support the Indian Arts and Crafts Act: Familiarize yourself with this law. It’s a truth-in-advertising law that prohibits misrepresentation in the marketing of Indian art and craft products within the United States. It’s your best tool for ensuring your "appreciation" is actually ethical.

- Diversify Your Feed: Follow contemporary Indigenous photographers like Matika Wilbur and her Project 562. They are actively replacing those old silhouettes with vibrant, colorful, high-definition portraits of modern Native life.