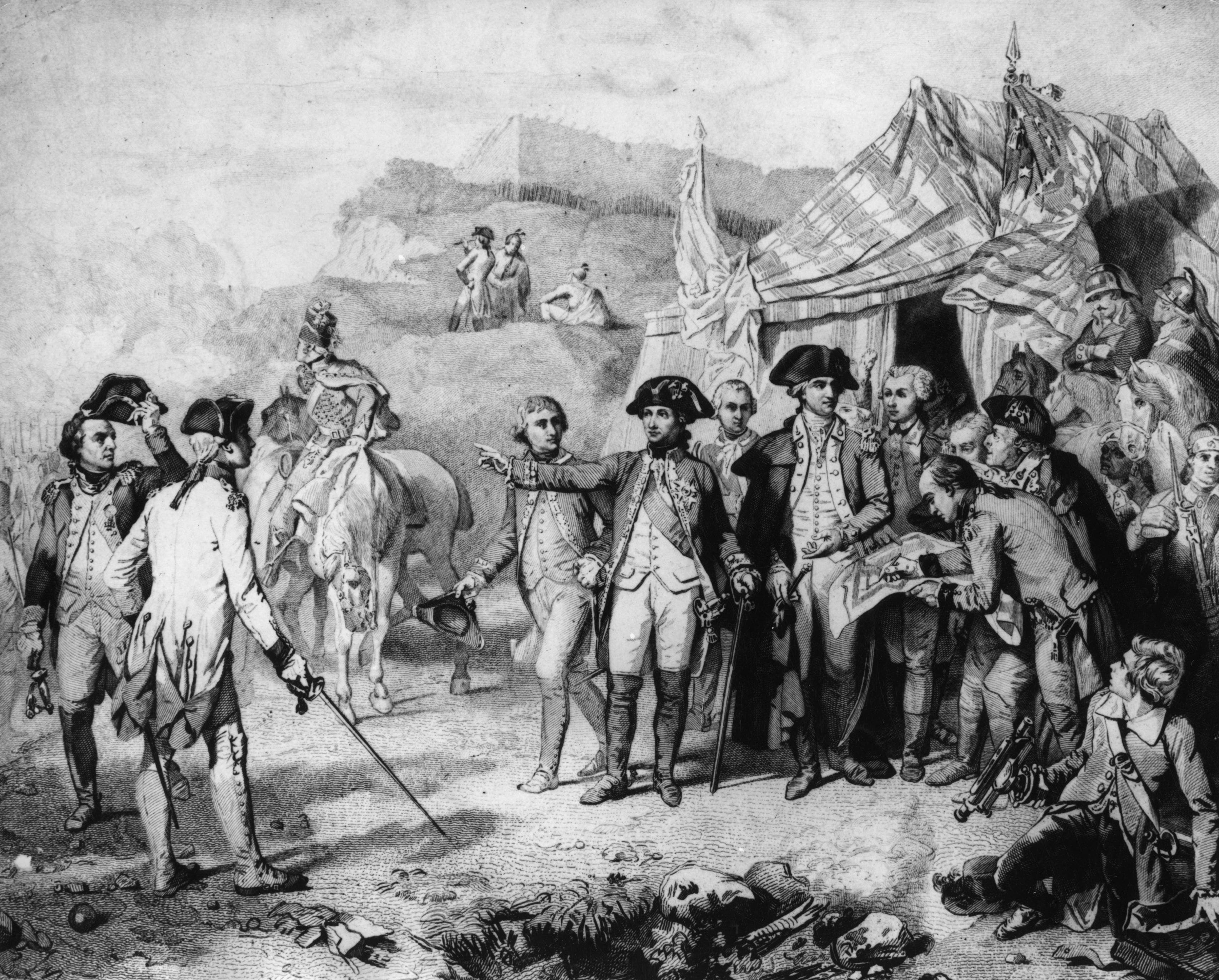

History repeats itself, or so they say. But in April 1862, history was just a weird, muddy coincidence. Everyone knows Yorktown because of George Washington and the British surrender in 1781. That’s the "famous" one. However, the siege of Yorktown Civil War story is arguably just as pivotal, though it’s way less celebrated in textbooks. It was a mess. It was a month of rain, shovel-work, and George B. McClellan being, well, George B. McClellan.

Imagine you’re a Union soldier in 1862. You’ve just landed on the Virginia Peninsula. You've got the biggest army ever assembled on the continent. You’re looking at Richmond—the Confederate capital—and it feels like the war could be over by summer. Then you hit Yorktown. You see some dirt walls and a bunch of cannons. Your commander freezes.

That’s basically the Peninsula Campaign in a nutshell.

The Massive Ego vs. The Muddy Reality

George McClellan was a "Young Napoleon." At least, that’s what people called him. He was brilliant at organizing things. The man could build a supply chain like nobody’s business. But when it came to actually pulling the trigger? Not so much. When he arrived at Yorktown in early April, he had about 100,000 men. Facing him was Confederate General John B. Magruder.

Magruder had maybe 13,000 guys.

The math is embarrassing. Honestly, it’s painful to look at the numbers. McClellan could have probably just walked over the Confederate lines. Instead, he stopped. He saw Magruder moving troops around in circles, making it look like there were thousands more than there actually were. Magruder was a theater fan, and he literally "staged" a defense. He had his men march into view, go behind a hill, and march back around again. It worked. McClellan blinked.

The siege of Yorktown Civil War wasn't a series of epic charges. It was a digging contest. For nearly a month, Union troops dug trenches and set up massive siege pieces—huge 13-inch mortars and 100-pounder Parrott rifles. While the Union dug, the Confederates waited, prayed for rain, and laughed at their luck.

📖 Related: Casualties Vietnam War US: The Raw Numbers and the Stories They Don't Tell You

Why Information Failed at Yorktown

You’d think with 100,000 people, someone would notice the enemy was faking it.

They didn't.

Part of the problem was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Allan Pinkerton was handling intelligence for McClellan. He was a great detective, sure, but a terrible military scout. He consistently doubled or tripled the number of Confederate troops in his reports. He told McClellan there were over 100,000 rebels waiting. This reinforced McClellan's natural tendency to over-prepare.

Professor Stephen Sears, who wrote the definitive book To the Gates of Richmond, highlights how this psychological trap paralyzed the Union. If your scouts tell you the enemy is a giant, you don't go poking them with a stick. You build a fort.

The Warwick River Bottleneck

Then there was the geography. The Warwick River doesn't look like much today, but in 1862, it was a nightmare. The Confederates had dammed it up. This turned small streams into wide, impassable lakes. The Union army was stuck in the mud. Literally. Soldiers wrote home about the "Virginia mud" being like glue. It sucked the shoes off their feet.

One of the few real fights happened at Lee’s Mill (Dam No. 1). On April 16, Vermont troops actually broke through the Confederate line. They crossed the water, got into the trenches, and... nothing happened. McClellan and his subordinates didn't send reinforcements. They let the Vermonters retreat. It was a classic "what if" moment. Had they pushed, the siege of Yorktown Civil War might have ended three weeks early.

👉 See also: Carlos De Castro Pretelt: The Army Vet Challenging Arlington's Status Quo

The Great Disappearing Act

By May 3, McClellan was finally ready. He had his massive guns in place. He was going to rain hell on Yorktown the next morning. It was going to be the most powerful bombardment in history.

He woke up on May 4 to silence.

The Confederates were gone.

General Joseph E. Johnston, who had taken over command of the Southern forces, knew he couldn't hold out against the big guns. He did the only sensible thing: he left in the middle of the night. He left behind "quaker guns"—logs painted black to look like cannons from a distance. The Union army walked into Yorktown and found empty trenches and dummy artillery.

It was a humiliating "victory."

The Human Cost of Waiting

While there wasn't a massive body count from bullets at Yorktown, the disease was staggering. Camp life in a swamp is a death sentence. Typhoid, malaria, and dysentery ripped through the Union ranks.

✨ Don't miss: Blanket Primary Explained: Why This Voting System Is So Controversial

- Water Quality: Most soldiers were drinking from shallow wells or the swamp itself.

- Sanitation: 100,000 men in a small space without modern plumbing is a recipe for disaster.

- Stress: The constant fear of a night attack kept men from sleeping, weakening their immune systems.

By the time the Union moved past Yorktown, they were already a diminished force.

Long-Term Effects on the War

The siege of Yorktown Civil War delayed the Union advance by a full month. Why does that matter? It gave Robert E. Lee time to organize the defense of Richmond. If McClellan had moved fast, he would have faced a disorganized mess. Instead, he gave the South a breather.

Historians like James McPherson often point out that this delay changed the entire trajectory of the war. If the war ends in 1862, does slavery end? Probably not in the same way. The Emancipation Proclamation wasn't a thing yet. A quick Union victory might have led to a negotiated peace that kept the status quo. In a weird, dark way, McClellan’s hesitation at Yorktown ensured the war became a "total war" that eventually destroyed the institution of slavery.

Modern Perspectives on the Site

If you go to Yorktown today, you see the Revolutionary War sites first. They’re the big draw. But if you look closer, you can see the Civil War earthworks cutting right through the older battlefields. The National Park Service has preserved some of these "dual" fortifications. It’s a strange feeling to stand on a spot where two different wars, fought 80 years apart, literally occupy the same dirt.

The siege of Yorktown Civil War is a lesson in the dangers of perfectionism. McClellan wanted the perfect battle. He wanted everything lined up, every gun in place, and every supply wagon accounted for. In his search for perfection, he lost his opportunity.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you are digging into the siege of Yorktown Civil War, don't just stick to the standard battlefield summaries. To really get what happened, follow these steps:

- Read the Official Records (OR): These are the digitized primary reports from the officers on the ground. Look for "Series 1, Volume 11." It contains the actual telegrams between McClellan and Lincoln. The tension is palpable.

- Study the Maps of the Warwick River: Most people assume Yorktown was just a town. The siege actually stretched across the entire peninsula. Looking at the dam locations (Dam No. 1, No. 2, etc.) explains why the Union couldn't just "flank" the position.

- Visit the Yorktown Victory Center: They have specific exhibits on the 1862 siege. Pay attention to the engineering tools. The sheer amount of dirt moved by these men with simple shovels is mind-blowing.

- Compare the "Quaker Guns": Look up photos of the dummy cannons used at Yorktown and Manassas. It’s a fascinating look at the psychological warfare used by the South to compensate for their lack of industrial power.

The Siege of Yorktown in 1862 proves that in war, the person who moves fastest usually wins, regardless of who has the bigger guns. McClellan had the guns. Magruder had the guts and the stagecraft. In the end, the stagecraft won the month.