May 13, 1981, started out as just another beautiful Wednesday in Rome. The sun was out. St. Peter’s Square was packed with about 20,000 people, all buzzing with energy, waiting for a glimpse of the "People’s Pope." John Paul II was doing his usual thing—riding in an open-top Fiat Campagnola, leaning over to bless children, and shaking hands with the crowd. It was intimate. It was joyful.

Then the shots rang out.

Four bullets. That’s all it took to change the course of the 20th century. One hit the Pope in the abdomen, another grazed his elbow, and another hit his index finger. The world stopped. You’ve probably seen the grainy footage or the iconic photos of the white-clad figure collapsing into the arms of his aides, but the shooting of Pope John Paul II is a story that goes way deeper than a simple assassination attempt. It’s a mess of Cold War politics, weird coincidences, and a forgiveness story that honestly feels like it belongs in a movie.

The Man with the Browning Hi-Power

The guy who pulled the trigger was Mehmet Ali Ağca. He wasn't some random lunatic who just decided to show up that day. He was a 23-year-old Turkish national with a rap sheet and a history of being associated with the Grey Wolves, a far-right militant group in Turkey. He’d actually escaped from a Turkish prison years earlier after being convicted of murdering a journalist.

Basically, he was a pro.

Ağca didn't act alone, or at least that’s what investigators spent decades trying to prove. He had help getting into Italy. He had money. He had a 9mm Browning semi-automatic pistol that worked perfectly. When he fired into the crowd at 5:17 PM, he wasn't just aiming for a man; he was aiming for a symbol of Western resistance against the Soviet bloc.

The crowd didn't just stand there, though. A nun, Sister Letizia, actually tackled Ağca before he could get more shots off or slip away into the chaos. Others jumped in. It was a scramble. Meanwhile, the Popemobile sped away, racing toward the Gemelli Hospital.

👉 See also: Statesville NC Record and Landmark Obituaries: Finding What You Need

Was there a "Bulgarian Connection"?

This is where things get really murky. For years, the prevailing theory was the so-called "Bulgarian Connection." The idea was that the KGB was terrified of John Paul II because of his support for the Solidarity movement in Poland. If Poland fell to anti-communist sentiment, the whole Soviet domino set might go with it.

So, the theory goes, the KGB asked the Bulgarian secret service to hire a Turkish hitman to keep their hands clean. Ağca himself eventually pointed the finger at three Bulgarian officials. He claimed they helped him plan the logistics in Rome. But here’s the kicker: he later took it all back. Then he said he was the Messiah. Then he changed his story again.

Because of his wildly inconsistent testimony, the "Bulgarian Connection" remains one of those historical debates that will never truly be settled. In 2006, an Italian parliamentary commission concluded that the Soviet Union was indeed behind the attack, but even today, many historians say the evidence is circumstantial at best. It's a classic Cold War whodunit.

The Medical Miracle and Our Lady of Fatima

The Pope almost died. Seriously. He lost an incredible amount of blood. When he arrived at the hospital, his blood pressure was plummeting, and doctors were scrambling. He underwent five hours of surgery.

But John Paul II didn't see his survival as a win for modern medicine alone. He was convinced it was divine intervention. The shooting of Pope John Paul II happened on May 13—the anniversary of the first apparition of the Virgin Mary to the children of Fatima in 1917.

"One hand pulled the trigger, and another guided the bullet," he famously said.

✨ Don't miss: St. Joseph MO Weather Forecast: What Most People Get Wrong About Northwest Missouri Winters

He actually had one of the bullets that was removed from his body plated in gold and set into the crown of the statue of Our Lady of Fatima in Portugal. It’s still there today. It fits perfectly into a hole that was already in the crown. Kinda eerie, right?

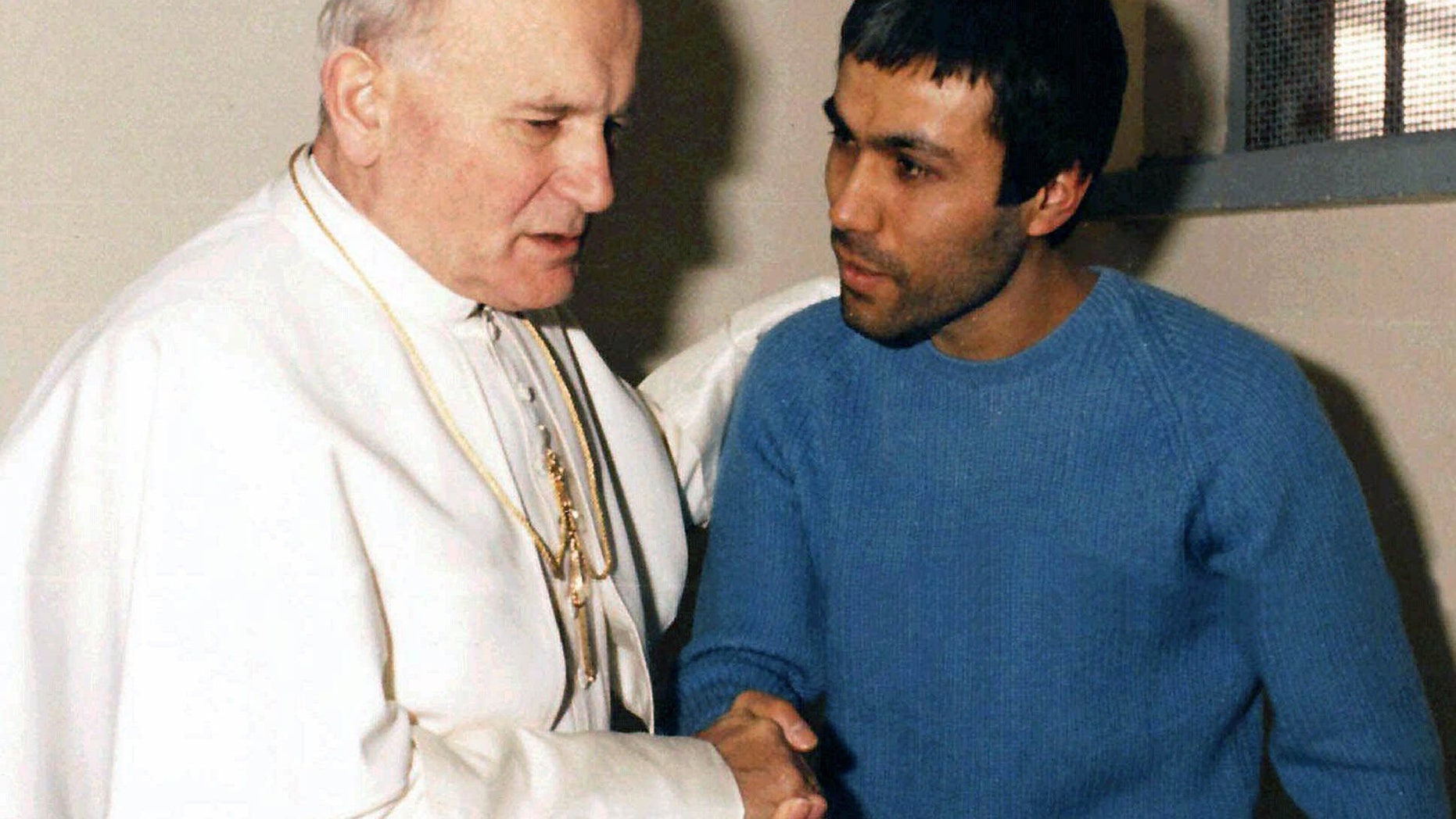

That Famous Meeting in a Prison Cell

Maybe the most "human" part of this whole ordeal happened two years later. In 1983, John Paul II went to Rebibbia Prison in Rome. He didn't go there to give a speech or visit the inmates in general. He went to sit down with Mehmet Ali Ağca.

They sat close. They whispered.

The Pope forgave him. Not just as a public PR stunt, but genuinely. He called Ağca his "brother." When he came out of that cell, he didn't tell reporters what they talked about. He kept it private. But the image of the victim sitting with his would-be assassin is still one of the most powerful symbols of mercy in history. It completely shifted how people viewed the Pope—not just as a political figurehead, but as someone who actually lived out the radical forgiveness he preached.

The Long-Term Fallout

The shooting didn't just leave physical scars; it changed how the Vatican operates. If you've ever wondered why the Popemobile looks like a glass box now, this is why. Before 1981, the Pope was incredibly accessible. After the shooting, the "bulletproof" era began. Security protocols were completely overhauled. The Swiss Guard became much more focused on modern counter-terrorism and tactical protection rather than just looking good in striped uniforms.

John Paul II also suffered from health complications for the rest of his life because of the wounds. Some historians argue that the physical trauma of the shooting accelerated his struggle with Parkinson's disease later on. He was never quite the same vigorous athlete he had been in the 1970s.

🔗 Read more: Snow This Weekend Boston: Why the Forecast Is Making Meteorologists Nervous

What Most People Get Wrong

People often assume this was a lone-wolf attack because Ağca was the only one caught in the act. But if you look at the travel records and the financing, it's clear he had a support network. Whether that network was the Grey Wolves, the Bulgarians, or some other shadowy group, we might never know for sure.

Another misconception is that the Pope was "safe" because he was in the middle of a crowd. In reality, that was the most dangerous place to be. The security at the time relied on the "goodness" of the people attending. That day ended that innocence forever.

How to Understand This History Today

If you’re looking to dive deeper into the shooting of Pope John Paul II, you have to look past the headlines and into the geopolitical climate of 1981. It wasn't just a crime; it was an act of war in the shadows.

Key Actionable Insights for History Buffs:

- Check the Source Material: If you want the real grit, look for the Mitrokhin Archive. It's a collection of notes from a KGB archivist that smuggled info out of Russia. It sheds a lot of light on Soviet attitudes toward the Polish Pope.

- Visit the Gemelli Hospital: There’s actually a small museum/statue area dedicated to the Pope there because he spent so much time in "Vatican Three," as he called the hospital.

- Analyze the Fatima Connection: Read the "Third Secret of Fatima." The Vatican released it in 2000 and claimed it predicted the assassination attempt. Whether you’re religious or not, the document's influence on the Pope’s actions is undeniable.

- Watch the 1981 News Reels: Seeing the transition from a cheering crowd to total, screaming chaos in seconds is a sobering reminder of how quickly history shifts.

The shooting of Pope John Paul II remains a pivotal moment because it showed the world that even the most "untouchable" figures are vulnerable. It also showed that how someone responds to violence—through forgiveness rather than retaliation—can be more impactful than the act of violence itself.

To truly understand the 20th century, you have to understand those few seconds in St. Peter's Square. It was the point where faith, Cold War espionage, and raw human survival all crashed into each other at the end of a 9mm barrel.