If you want to understand why Latin American relations with the United States are so perpetually tense, you don't look at a modern social media thread. You look at a book from 1956. Juan José Arévalo, the former president of Guatemala, wrote The Shark and the Sardine, and honestly, it’s one of the most blistering critiques of American foreign policy ever put to paper. It’s not a dry academic text. Far from it. It’s a fable. It’s a polemic. It’s a scream from a man who watched his successor get toppled by a CIA-backed coup.

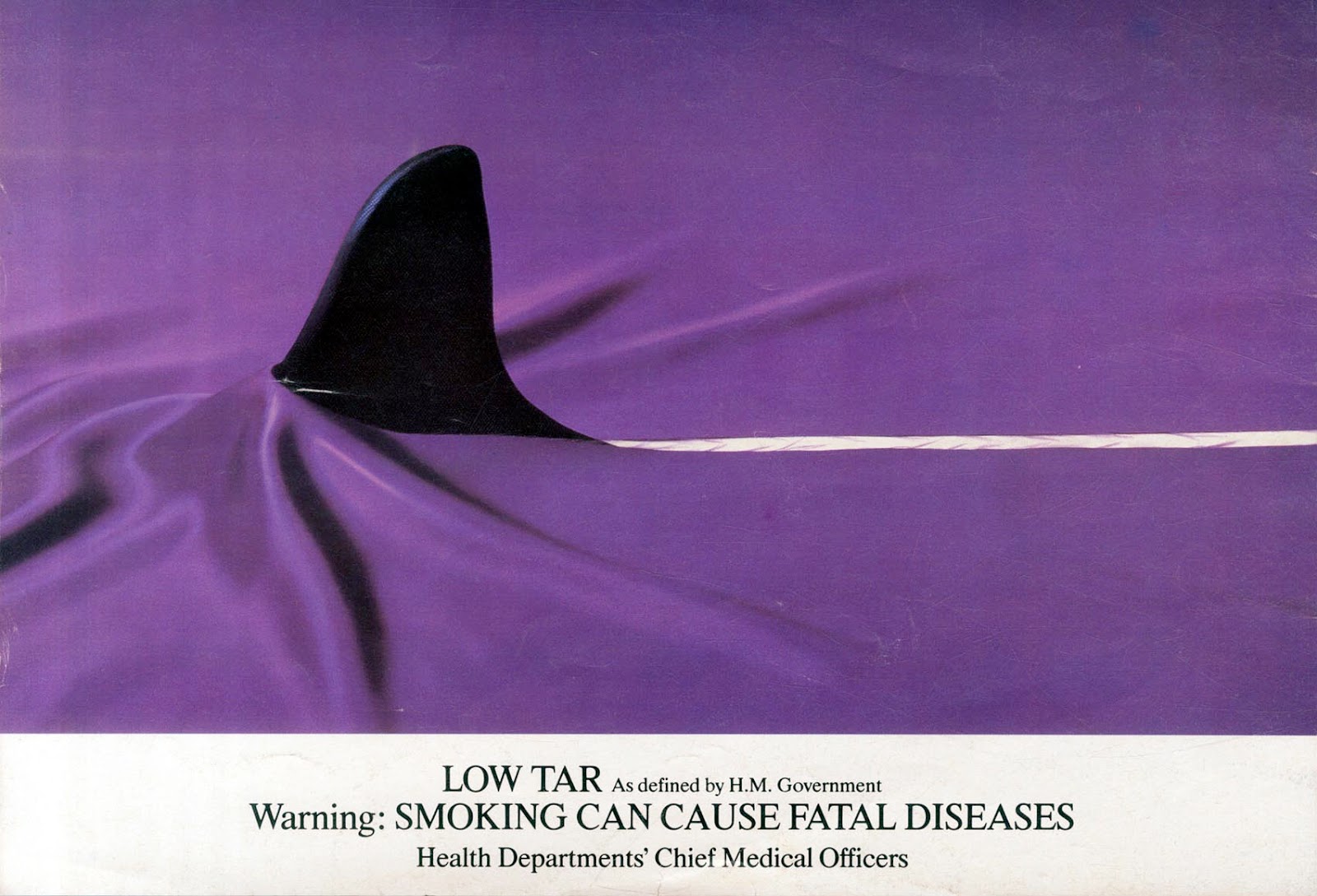

Arévalo wasn't some random radical. He was the first democratically elected president of Guatemala after the 1944 Revolution. He called himself a "spiritual socialist." When he wrote The Shark and the Sardine, he was living in exile. He had seen the machinery of the "North American" empire up close. The book basically argues that the relationship between the U.S. (the Shark) and Latin American nations (the Sardines) isn't a partnership. It’s a dinner.

What is The Shark and the Sardine actually about?

The core of the book is an allegory. Imagine a vast ocean. The Shark is the United States—powerful, hungry, and constantly talking about "brotherhood" and "democracy." The Sardines are the smaller, weaker nations of the South. The Shark invites the Sardines into all these fancy treaties and legal agreements. It talks about Pan-Americanism. It promises protection.

But Arévalo’s point is that the legal language is just a mask.

He spends a lot of time dissecting the Pan-American Union (which later became the OAS). To him, these weren't forums for cooperation. They were traps. He argues that the Shark uses international law to legitimize its own appetite. If a Sardine has something the Shark wants—like land for fruit or oil—the Shark finds a "legal" reason to take it. Or it just eats the Sardine and calls it "security."

It’s a brutal metaphor.

People often forget how much Arévalo focused on the "Wall Street" aspect of this. He wasn't just mad at the U.S. government; he was furious at the United Fruit Company. In his eyes, the State Department was basically the armed wing of American corporations. When the Sardines tried to pass laws to help their own people—like land reform—the Shark would suddenly claim its "rights" were being violated.

💡 You might also like: Brian Walshe Trial Date: What Really Happened with the Verdict

The prose is dense, poetic, and incredibly angry. You’ve got to remember the context. Arévalo wrote this after seeing Jacobo Árbenz, the man who followed him as president, ousted in 1954 because he tried to redistribute unused land owned by United Fruit. The CIA called it "Operation PBSuccess." Arévalo saw it as a Shark finishing its meal.

Why the 1961 English Translation Exploded

The book didn't just stay in Latin America. In 1961, it was translated into English by June Cobb and Stefan Baciu. This was right around the time of the Bay of Pigs. Suddenly, Americans were reading this scathing critique of their own country.

It became a sensation.

It was even mentioned in the New York Times and debated in Congress. Some called it "Communist propaganda." Others saw it as a necessary wake-up call. The book hit a nerve because it challenged the "Good Neighbor Policy" narrative that the U.S. had been pushing for decades. Arévalo basically said, "You aren't a good neighbor. You're a predator who wears a suit to the funeral of your victims."

The Legalism of the Shark

One of the most interesting parts of The Shark and the Sardine is how Arévalo breaks down the "treaties." He talks about the "Empire of Finance."

He argues that the U.S. doesn't just use guns; it uses debt. It uses contracts. He describes how Latin American diplomats were often coerced or bribed into signing agreements that effectively handed over their country's sovereignty. It’s what we’d call "neo-colonialism" today, but Arévalo was describing it in real-time.

📖 Related: How Old is CHRR? What People Get Wrong About the Ohio State Research Giant

- The Contract: A Sardine signs a deal for a loan.

- The Clause: Hidden in the fine print is a rule that says the Shark gets to control the Sardine's ports.

- The Result: The Sardine is no longer independent, but the Shark can say, "Hey, they signed the paper!"

He was particularly obsessed with the idea that "Pan-Americanism" was a one-way street. The U.S. wanted the markets of the South, but it didn't want the people of the South to have any actual power.

Does the Metaphor Still Hold Up?

Honestly? Kinda.

If you look at modern debates about the IMF, trade deals like NAFTA (or USMCA), and the way the U.S. uses sanctions, Arévalo’s ghost is everywhere. You can see his influence in the writings of Eduardo Galeano, specifically Open Veins of Latin America. Galeano took Arévalo’s anger and turned it into a historical epic.

But there are limitations to Arévalo’s view. He wrote this during the Cold War. Everything was binary. Today, the "Sardines" aren't all the same. Some have grown. Some have sought other "Sharks" like China or Russia to balance things out. The world is more multipolar now.

However, his critique of how powerful nations use the language of morality to cover up actions of self-interest is still dead on. Whenever a superpower talks about "defending democracy" while protecting its own mineral interests, you’re reading a chapter out of Arévalo’s book.

The Legacy of a President in Exile

Arévalo died in 1990. He lived long enough to see the Cold War end, but he never really saw a Latin America that was free from the dynamics he described.

👉 See also: The Yogurt Shop Murders Location: What Actually Stands There Today

The book remains a staple in political science classes across the continent. It’s often used to explain "Dependency Theory"—the idea that resources flow from a "periphery" of poor and underdeveloped states to a "core" of wealthy states, enriching the latter at the expense of the former.

It’s not a comfortable read for an American audience. It’s meant to sting. Arévalo didn't want to build bridges; he wanted to burn down the ones he thought were rigged.

How to Apply Arévalo’s Insights Today

If you’re interested in geopolitics or just want to understand why your neighbors to the south are often skeptical of U.S. intentions, here is how you can use the perspective of The Shark and the Sardine to analyze current events.

Analyze the "Why" Behind Treaties

When you hear about a new international trade agreement, don't just look at the "mutual benefits" mentioned in the press release. Look for the power imbalance. Is one side being forced to change its domestic laws (like labor or environmental rules) to satisfy the other? That’s the "Shark" writing the rules of the ocean.

Look at Corporate-Government Synergy

Arévalo was one of the first to highlight how government policy often follows corporate profit. Check the history of companies operating in developing nations. If a government starts leaning toward nationalization or heavy regulation of a foreign company, watch how the foreign company's home government reacts. Is it about "human rights," or is it about protecting the "Shark's" lunch?

Recognize the Language of Paternalism

Pay attention to when powerful nations treat smaller ones like children who don't know what's best for them. Arévalo hated the "big brother" rhetoric. Real partnership requires a level playing field, something he argued was impossible as long as one side held all the capital and the cannons.

Study the History of Interventionism

Read up on the 1954 Guatemalan coup (Operation PBSuccess). It’s the event that radicalized Arévalo’s worldview. Understanding that specific history makes The Shark and the Sardine move from a "metaphor" to a literal account of a country being dismantled for the sake of a fruit company. It provides the necessary context for the cynicism found in the book.

Read the Primary Source

Don't just take a summary's word for it. Find a copy of the 1961 translation. The language is incredibly evocative. It’s a rare chance to read the perspective of a head of state who was directly affected by the policies he’s criticizing. It offers a "from the inside" look at the failure of 20th-century diplomacy that you won't find in most U.S. history textbooks.