History is messy. Sometimes, it’s also incredibly quiet. That quiet is exactly what makes The Secret Path so hauntingly loud. It isn't just a movie or a simple animated short; it’s a reckoning. If you’ve ever sat through the 60-minute journey created by the late Gord Downie and illustrator Jeff Lemire, you know it doesn’t feel like a standard "entertainment" experience. It feels like an obligation. A heavy, beautiful, and necessary one.

People often ask what makes The Secret Path different from other documentaries or films about Canada's residential school system. Honestly? It's the lack of dialogue. It relies on music and ink.

What Most People Get Wrong About The Secret Path

A lot of folks go into this thinking it’s a biopic. It’s not. Not in the traditional sense, anyway. You aren't getting a birth-to-death timeline of Chanie Wenjack. Instead, you're getting the raw, visceral experience of a twelve-year-old boy trying to walk 600 kilometers home. Alone. In the snow. With nothing but a cotton shirt.

Chanie—misnamed "Charlie" by his teachers—escaped the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in 1966. He died of exposure and hunger beside the railroad tracks.

The film serves as a visual album. It’s the final project of Gord Downie, the frontman of The Tragically Hip, who spent his last months on earth obsessed with making sure Canadians didn’t forget this kid’s name. Downie was dying of brain cancer while he recorded these songs. You can hear it in his voice. There’s a frantic, crumbling texture to the vocals that mirrors Chanie’s physical decline.

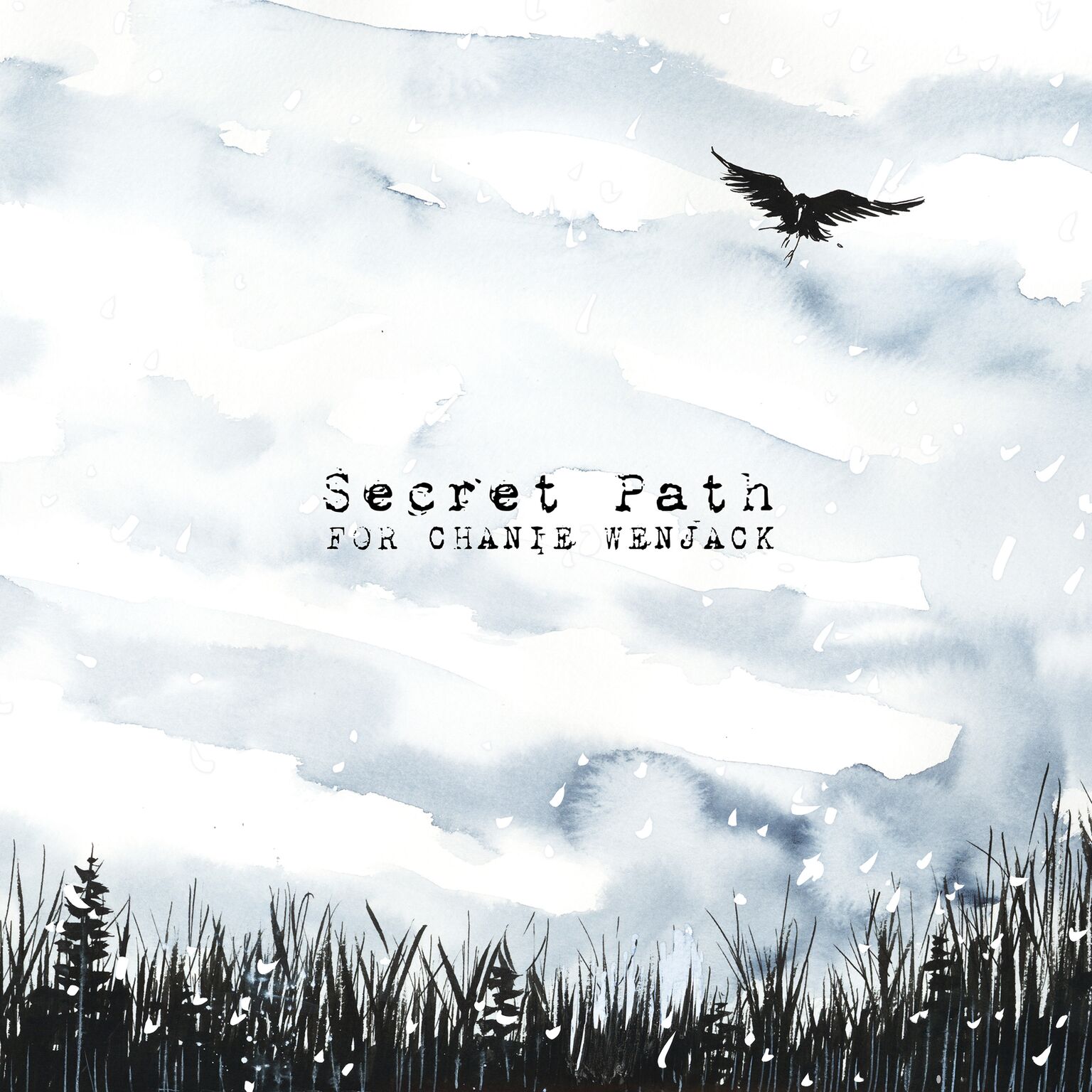

People sometimes mistake the film for a children's story because it’s animated. That’s a mistake. While it is used in classrooms now, the imagery is stark. Jeff Lemire’s art style—known for Essex County and Sweet Tooth—is perfect here. He uses washed-out blues and greys. The ink bleeds. It looks like a memory that’s being washed away by the rain, which is exactly the point.

The Power of the "Secret" in the Path

Why is it called a "secret" path? Because for decades, the reality of these schools was a secret to the vast majority of non-Indigenous people. It was a hidden geography of pain. Chanie’s path followed the railway tracks because he thought they would lead him back to his father. He didn't realize how vast the distance was.

He had "the secret path" in his head.

👉 See also: Why the Good Life Lyrics by Onerepublic and Relo Still Hit Different

The film captures the isolation. You see the vastness of the Ontario wilderness. It’s beautiful but indifferent. The animation doesn't shy away from the hallucinations Chanie likely experienced. He sees his family. He feels the warmth of a home that is hundreds of miles away. It’s gut-wrenching.

The Collaboration That Made It Happen

The origin of the project is pretty unique. It started with Gord Downie’s poems. He wrote ten poems that became the ten tracks of the album. Then he reached out to Jeff Lemire.

Lemire has talked about this in interviews, noting that he didn't want to over-illustrate. He wanted the music to breathe. The resulting film is a seamless blend where the lyrics act as the internal monologue Chanie never got to speak.

- The Music: Produced by Kevin Drew (of Broken Social Scene) and Dave Hamelin. It’s atmospheric. It isn't "rock." It’s more like a prayer or a long, sustained cry.

- The Visuals: Lemire used a limited palette. Mostly watercolor and ink. This keeps the focus on Chanie’s yellow windbreaker—the only bit of bright color in a frozen world.

- The Intent: It was never about making a "hit." It was about "reconciliaction"—a word Downie coined to describe taking actual steps toward fixing a broken relationship between nations.

Why This Film Still Matters in 2026

You might think, "Okay, this came out in 2016. Why are we still talking about it?"

Because the conversation hasn't finished. In the years since The Secret Path premiered, more remains have been found at former residential school sites across North America. The film has transitioned from a contemporary art piece into a foundational educational tool.

It’s easy to read a textbook and see a statistic: "150,000 children attended these schools." It’s much harder to watch a single boy try to light a match in a windstorm and not feel your chest tighten. The film forces empathy in a way that data cannot.

One detail often overlooked is the involvement of the Wenjack family. This wasn't just some celebrities co-opting a tragedy. Downie traveled to Marten Falls to meet Chanie's sisters, Pearl and Annie. They gave their blessing. They wanted the story told. Pearl has often said that for a long time, Chanie was just a boy who disappeared. Now, because of this film, he’s a symbol of every child who never made it back.

The Real History vs. The Artistic Interpretation

While the film is poetic, the facts are even more brutal. Chanie was found with a small glass jar containing seven matches. He had survived for 36 hours in sub-zero temperatures before his body gave out. The film handles this with incredible grace. It doesn't show the death as a graphic event, but as a transition—a boy finally finding the warmth he was looking for, even if it's not in this world.

✨ Don't miss: Lily Phillips 101 Men Porn Video: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Some critics at the time wondered if a white rock star was the right person to tell this story. It’s a fair question. Downie himself acknowledged this. He saw his role not as the "voice" of Indigenous people, but as a megaphone. He used his platform at the height of his own tragedy to point the spotlight elsewhere. That’s a nuance that makes the film even more layered.

The Lasting Legacy of the Wenjack Story

If you haven't seen it, find the CBC broadcast version. It includes footage of Downie performing the songs live, interspersed with the animation. Seeing a man who is clearly dying sing about a boy who died too young creates a strange, powerful parallel. It’s about the fragility of life and the weight of legacy.

The Secret Path inspired the creation of the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund. This isn't just a film that sits on a shelf. It’s a film that started a movement of "Legacy Spaces" in offices and schools.

People often forget that Chanie wasn't the only one. He was just the one whose story was documented by Maclean’s magazine in 1967, which is how Downie first discovered the history. There were thousands of Chanies.

The film serves as a gateway. It’s the starting point for people who don't know where to begin with Indigenous history. It doesn't give you all the answers. It doesn't offer a "happy" ending where everything is fixed. It just asks you to look. To acknowledge. To remember.

How to Engage With The Secret Path Today

If you’re planning on watching or sharing this, here is the best way to approach it.

👉 See also: Michael Stuhlbarg Doctor Strange: Why the MCU Wasted Its Best Villain Setup

First, don't watch it as a background movie. It’s short, but it’s heavy. You need to sit with it. Listen to the lyrics of "The Stranger" or "Seven Matches." The lyrics are literal. "I am a stranger / You can't see me / I am a stranger / Follow me."

Second, look into the actual history of the Cecilia Jeffrey school. Understanding the systemic nature of what Chanie was fleeing makes his "secret path" even more heroic. He wasn't just running home; he was reclaiming himself.

Finally, check out the work of Indigenous creators who are telling similar stories from a first-person perspective. The Secret Path is a vital bridge, but it’s only the beginning of the road.

Practical Steps for Continued Learning:

- Watch the film on YouTube or the CBC Gem app. It’s widely available because the creators wanted it to be seen.

- Visit the Downie-Wenjack Fund website. They have actual curriculum guides if you are an educator or just someone who wants to learn more than a 20-minute video can provide.

- Read "The Lonely Death of Charlie Wenjack" by Ian Adams. This is the 1967 article that inspired Gord Downie. It’s a masterclass in long-form journalism and provides the gritty details the film abstracts into art.

- Support Indigenous-led arts organizations. The best way to honor the intent of The Secret Path is to ensure that the next "Secret Path" is told by an Indigenous filmmaker.

There’s no "closing the book" on this story. You don't finish the film and move on. You finish it and you carry a piece of Chanie with you. That’s the real power of The Secret Path. It turns a historical footnote into a living, breathing conscience. It’s a quiet film that demands a very loud response in how we treat one another and how we acknowledge the truth of the land we stand on.