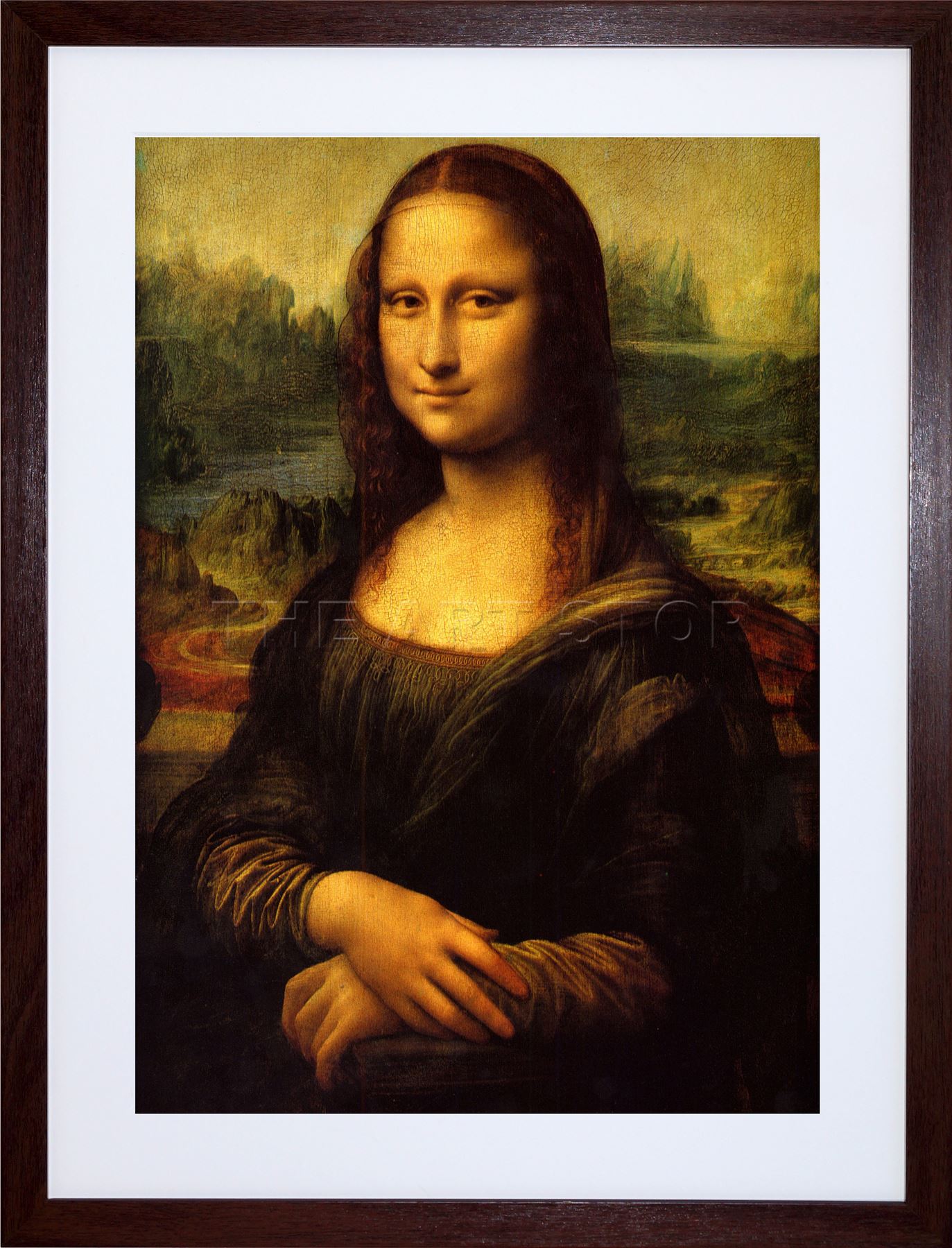

Everyone knows the woman with the smirk. She sits behind bulletproof glass in the Louvre, mobbed by tourists holding iPhones, basically the most famous face on the planet. But what if she had a younger sister? For decades, art historians, wealthy collectors, and forensic scientists have been arguing over the second Mona Lisa painting, often called the Isleworth Mona Lisa. It isn't just a copy. It’s a full-blown mystery that challenges everything we think we know about Leonardo da Vinci’s workflow.

Honestly, the art world is usually pretty stuffy, but this specific painting turns experts into combatants. Some say it's a masterpiece Leonardo started years before the Louvre version. Others think it’s just a very good "fan fiction" piece from the 16th century. If you look at them side-by-side, the differences are jarring. The woman in the second Mona Lisa painting looks significantly younger. Her face is narrower. She’s framed by two large columns that aren't in the Louvre version. It’s like seeing a prequel to a movie you’ve watched a thousand times.

What is the Isleworth Mona Lisa exactly?

The story is kinda wild. In 1913—right around the time the original Mona Lisa was being returned to the Louvre after a famous heist—an English art connoisseur named Hugh Blaker found this "earlier" version in an old manor house in Somerset. It had been sitting there for a century, tucked away. Blaker bought it and took it to his studio in Isleworth, London. That’s where the name comes from.

He was convinced he’d found a treasure. Since then, the painting has passed through the hands of Henry Pulitzer and eventually a Swiss consortium. The Mona Lisa Foundation in Zurich has spent years trying to prove its authenticity. They aren't just guessing; they’ve put this thing through the ringer. We’re talking carbon dating, "digital geometry" tests, and infrared reflectography.

The weirdest part? The painting is unfinished. The background is sparse compared to the misty, ethereal mountains behind the Louvre’s Lisa. But the face? It’s hauntingly similar. Leonardo was notorious for not finishing his work. He’d get bored or distracted by a bird flying past his window or a new hydraulic engineering project. This lack of a finished background is actually used by some as evidence for its authenticity. Why would a forger, trying to make a quick buck, leave the most recognizable part of the landscape half-done?

The "Two Versions" Theory: Why it makes sense

If you’re a Da Vinci skeptic, you probably think he only ever painted one Lisa. But history says otherwise.

Agostino Vespucci, a contemporary of Leonardo, wrote a note in 1503 mentioning that Leonardo was working on a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo. Then, jump forward to 1517. Another record describes Leonardo showing a portrait of a "certain Florentine lady" to a Cardinal. The problem? The Louvre painting doesn't quite match the descriptions from the earlier date.

🔗 Read more: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

This led experts like Jean-Pierre Isbouts to suggest that Leonardo actually painted two separate versions. It was his "Beta" and "1.0" versions. He might have started the second Mona Lisa painting for Lisa’s husband, Francesco del Giocondo, but never gave it to him. Then, years later, he started a new one for himself—the one that ended up in France.

Think about it. Artists do this all the time. They iterate. Leonardo was a perfectionist who obsessed over sfumato, that smoky blurring of edges. It’s totally plausible he spent years practicing the composition on one canvas before perfecting the expression on another.

Science vs. Snobbery

The battle over the second Mona Lisa painting is basically a fight between "connoisseurship" and "hard science."

The traditionalists, like Martin Kemp from Oxford, have been pretty vocal about their doubts. Kemp argues that the painting is on canvas, while Leonardo almost always painted on wood (poplar). He also thinks the "spirit" of the painting just isn't there. It’s a gut feeling. To these experts, the Isleworth version looks too stiff. They see it as a high-quality copy by a student in Leonardo's workshop, someone like Salai or Francesco Melzi.

But then you have the tech people.

- Carbon-14 Dating: Tests conducted by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology dated the canvas to between 1410 and 1455. This at least proves the material is old enough. It wasn't painted in someone's basement in the 1920s.

- The "Hidden" Sketches: Under-drawing reveals that the artist made changes as they went. Forgers usually copy exactly what they see on the surface. They don't make "mistakes" or adjustments underneath the paint because they’re following a map. The Isleworth painting has these "pentimenti," or shifts in the artist's mind.

- Geometry: Alfonso Rubino, a sacred geometry expert, claims the Isleworth painting follows the same complex proportional grids that Leonardo used in his other works.

Is it possible they're both right? Maybe it’s a "studio work" where Leonardo did the face—the most important part—and left the rest to a talented apprentice. That happened constantly in the Renaissance. It was a factory system, not a solo act.

💡 You might also like: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

The Prado Version: Another contender

Just to make things more confusing, there is another second Mona Lisa painting in the Prado Museum in Madrid. For a long time, it was covered in black overpaint and looked like a cheap imitation.

Then, in 2012, they cleaned it.

Suddenly, a stunningly beautiful landscape appeared. The woman in the Prado version has eyebrows (the Louvre one doesn't) and looks much more vibrant. The research proved it was painted side-by-side with the original in Leonardo's studio. It’s almost a frame-by-frame copy made in real-time. This discovery changed the game because it proved that there was "Mona Lisa fever" even while the original was being painted. If the Prado version exists as a simultaneous copy, the idea of an earlier Isleworth version becomes much more believable. Leonardo’s studio was a hub of repetition and experimentation.

Why we can't let it go

We are obsessed with the second Mona Lisa painting because we want more Leonardo. He left us fewer than 20 finished paintings. Every time a "new" one surfaces—like the Salvator Mundi, which sold for $450 million despite massive controversy—the world loses its mind.

The Isleworth Mona Lisa represents a younger, fresher version of the woman we think we know. She looks less like a myth and more like a person. If it’s real, it gives us a window into Leonardo’s 1503 brain instead of his 1510 brain.

But there’s also the money. A "real" Leonardo is worth more than a small country’s GDP. The stakes are so high that it’s hard to trust anyone involved. The owners want it to be real for the value. The Louvre wants theirs to be the only "real" one for the prestige. The truth is likely buried somewhere in the middle, in the chemical composition of the pigments and the way the brush strokes move across the chin.

📖 Related: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

What to look for yourself

If you ever get the chance to see high-res scans or the painting itself on tour, check out these three things:

- The Pillars: The Isleworth version has distinct columns on the left and right. In the Louvre version, you can only see the bases of these columns (the "plinths").

- The Hands: Leonardo was the master of hands. In the Isleworth painting, the hands are beautifully executed, but some say they lack the skeletal precision of his later work.

- The Smile: It’s more of a smirk in the second Mona Lisa painting. It’s less ambiguous, which is why some critics think it’s a less sophisticated work.

How to explore the mystery further

You don't need a PhD in Art History to form an opinion. If you're fascinated by the possibility of a lost masterpiece, start by comparing the "Brushstroke Theory" results. Computers have analyzed the "pixels" of the Isleworth painting and compared them to Leonardo's known works, like the Lady with an Ermine.

Next, look into the "Lustrous" theory. Leonardo was experimenting with new ways to make skin look like it was glowing from within. Look at the neck of the Isleworth painting. Does it have that translucent, layered quality? Or does it look flat?

The best way to engage with the second Mona Lisa painting mystery is to look at the evidence yourself. Don't just take a critic's word for it. The art world is full of egos and "gatekeepers" who hate being proven wrong. Read the reports from the Mona Lisa Foundation, then read Martin Kemp’s rebuttals. The truth of Leonardo is never a straight line; it's always a series of beautiful, smoky layers.

Check the exhibition schedules for the "Earlier Mona Lisa." It occasionally tours the world, moving from Singapore to Shanghai to Italy. Seeing it in person is the only way to truly feel if that "Leonardo energy" is there. Until then, the second Mona Lisa painting remains the most expensive and beautiful "maybe" in history.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Search for "Infrared Reflectography Isleworth Mona Lisa" to see the hidden drawings beneath the paint.

- Compare the "Prado Mona Lisa" and the "Isleworth Mona Lisa" side-by-side to see how different students and versions diverged from the original.

- Track the provenance (ownership history) of the Somerset manor house where the painting was found to see how it likely traveled from Italy to England.